From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

25-27 Oct 1214 |

RLP, 122, 123; RLC, i, 174-5 |

||

27 Oct 1214 |

RLP, 122-2b; RLC, i, 174b; The Chronicle of the Election of Hugh Abbot of Bury St Edmunds and Later Bishop of Ely, ed. R.M. Thomson (Oxford, 1974), 116-17 |

||

28 Oct 1214 |

RLP, 123 |

||

28 Oct 1214 |

RC, 202 |

||

29-30 Oct 1214 |

RC, 202; RLP, 122b-3; RLC, i, 174b-6b |

||

30 Oct 1214 |

RLC, i, 176-6b |

Hardy ('Itinerary') locates the King at the Tower of London on 31 October, source untraced. |

|

1-2 Nov 1214 |

Foedera, 126; RC, 202; RLP, 112b; RLC, i, 173b-4, 202b |

At Reading on 26 October, there was a significant rearrangement of custodies, with the transfer of Wallingford and its castle to the sheriff of Berkshire, John of Wiggenholt.1 In due course, the honour of Wallingford was to earn mention in Magna Carta, clause 43. The intention of this clause was to protect the tenants of Wallingford, as of the honours of Peverel of Nottingham, Boulogne, Lancaster or any other great barony now in the King's custody, from being treated unfairly. When, in the twelfth century, such honours had been held by barons serving as mesne lords between the honour's tenantry and the king, the honours' tenants, many of them relatively humble knights, had enjoyed a degree of protection and cushioning in their relations with the crown that they no longer enjoyed once these estates 'escheated' (or returned) to the direct management of the crown. As Christopher Tilley has recently emphasised, there may indeed have been a disproportionate sense of resentment against King John expressed by the tenantry of the greater escheats. Certainly, after 1215 Wallingford produced a large number of rebel knights.2

On 27 October, whilst the King was at Windsor, orders went out for an heiress to be released into the custody of Robert de Ros, himself one of the future baronial twenty-five.3 There were also new arrangements for the custody of Annora de Braose, sister of Giles bishop of Hereford and wife of the marcher baron, Hugh de Mortimer lord of Wigmore, recently permitted to inherit his father's estates. Annora was one of the ongoing victims of the King's great purge of the Braose family. Since 1210, this had resulted in the exile and death in France of her father, William de Braose, and the deliberate starving to death of her mother and elder brother. Annora herself had been taken prisoner with her mother, in Ireland, in 1210. She was now removed from the custody of the King's alien constable at Windsor, Engelard de Cigogné, and handed over to the keeping of the papal legate, Nicholas of Tusculum. She remained, nonetheless, deliberately separated from either her father's or her husband's families.4 Here brother, bishop Giles of Hereford, is recorded at court, very briefly, on 28 October.5

Having reached Westminster on 28 October, the King then made for the Tower, by no means the most luxurious of royal residences, but far more easily defended in time of trouble than the relatively unfortified palace of Westminster. From the Tower, it was possible for English kings to keep a close eye on the politics of the city of London. In the ongoing attempt to heal the wounds of the papal interdict, letters were dispatched declaring that the King had remitted all anger against the brothers, Hugh and Jocelin of Wells. Elected bishops of Lincoln and Bath earlier in the reign, Hugh and Jocelin were former royal servants who had chosen, after 1208, to side with the clerical exiles rather than to support their former master, King John.6 With particular reference to bishop Jocelin, from the Tower, on 30 October, the King wrote to the prior and convent of Glastonbury, summoning them to attend a council set to meet at Reading a fortnight after Christmas, i.e. on 8 January 1215 (two days after the feast of the Epiphany). Here, with the assistance of the papal legate and archbishop Langton, it was hoped that peace might be made in the longstanding dispute over custody of Glastonbury abbey and its estates.7 Since the 1190s, these had been claimed as a perquisite by the bishops of Bath and Wells. What is significant here is not only the appeasement of bishop Jocelin but the fact that the King was already planning a great January council, a full two and a half months in advance.

On the previous day, 29 October, the keepers of the port of Dover had been instructed to supply passage overseas for four royal ambassadors, including the abbots of Reading and Waverley, sent overseas.8 Almost certainly, this was part of the King's continuing attempt to secure papal support amidst the ongoing threat of civil war. Throughout this week, arrangements continued for the garrisoning and provisioning of the King's castles. Peter de Maulay at Corfe was sent £100, 10 mounted crossbowmen and a 'white' (presumably silver) cup as a gift for his mother.9 On 30 October, he was instructed to release 20,000 crossbow bolts, to be taken to the King's castle at Marlborough.10 Berkhamsted castle was provisioned with salt pork.11 Twenty crossbowmen were sent to Engelard at Windsor, and a further twenty to Philip Mark at Nottingham, to garrison the bailey of Nottingham castle.12 Various of these orders refer to the supervisory role now being played in the King's military affairs by the Norman knight, Fawkes de Bréauté, and the west-country administrator, Godfrey of Crowcombe. Both of these men were to go on to distinguished, though controversial, careers in royal service, in Godfrey's case lasting long into the 1230s.

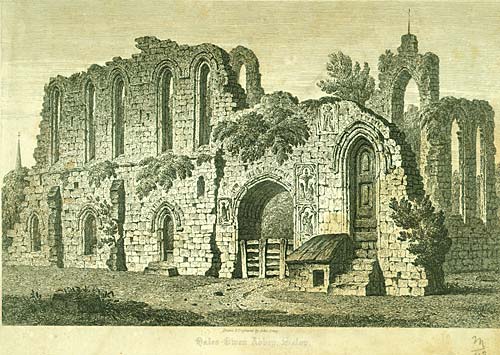

Already, before his return to London, from Windsor on 27 October, the King had instructed the sheriff of Staffordshire to transfer the royal manor of Halesowen to the keeping of Peter des Roches, bishop of Winchester.13 In London, on the following day, the King issued an elaborate charter granting Halesowen to bishop Peter so that he might found there an abbey of whatever religious order he might choose.14 This charter supplies important evidence of the rewards that des Roches received for his service as justiciar and regent. It was one of many such royal favours that des Roches was to assemble over the next twenty years, during the course of a career as one of the most prolific founders of new abbeys and priories in England. The intention here was to foster religion by preserving the memory and ensuring spiritual services for the soul of an alien Frenchmen for whom, in general, the English showed scant affection. Halesowen was bestowed in due course by bishop Peter upon the Premonstratensian order.

Two aspects of the King's charter granting Halesowen are worthy of particular notice. The first is that its witness list includes the names of several royalists, as does the witness list to a charter issued on the following day, at the Tower, granting Walter de Gray, bishop of Worcester, an annual fair at his manor of Stratford-upon-Avon.15 Since Halesowen lay within the diocese of Worcester, there was almost certainly an element of quid pro quo here. Walter de Gray was expected to support bishop Peter's new foundation, just as earlier that year, bishop Peter seems to have been instrumental in the promotion of Walter, previously royal chancellor, to the vacant bishopric of Worcester. To judge from the witness lists to these charters, the King was for the most part surrounded by his own henchmen (Peter des Roches, Walter de Gray, William of Cornhill bishop-elect of Coventry, William Brewer, Brian de Lisle, Richard Marsh). Even so, the bishop of Hereford (Giles de Braose), Saher de Quincy, earl of Winchester, and William de Aubigny of Belvoir, are also to be found at court, all of them future members of the rebel party.16 The most notable absentees are the English bishops who had sided with Langton during the Interdict and whose presence at court is not attested until late November, when they came not so much to support the King as to seek resolution of their own private grievances.

The Halesowen charter is also remarkable for the list of liberties appended to the King's grant of the manor.17 These included soke and sake, toll and team, infangentheof and utfangentheof: the by now traditional appurtenances of independent lordship. But to these were added quittance from shires, hundreds, pleas, suits of foresters, disputes, money given for forfeits, murdrum, wapentakes, scutage, gelds, danegelds, hidages, assizes, castle works, works on parks, bridges or quays, ferdwyte, leirwyte, hundredpenny, tithingpenny, hengwyte, flemesfryth, hamsoken, warpenny, bloodwyte, and fitwyte. Various of these liberties were pre-Conquest in origin, some of them semi-mythical. All of them are familiar from royal charters stretching back to the twelfth century and beyond. What is striking about their great assembly here is the way in which they testify to belief in an age old tradition of 'liberties', many of them Anglo-Saxon rather than Norman, stretching back to the by now mythologized reigns of Edward the Confessor and King Alfred, authors of what was generally considered, by 1214, to be the immemorial 'law' of England. Peter des Roches, and his master, King John, were not in general regarded as great respecters of this 'law'. Nonetheless, even in the process of rewarding des Roches, King John was obliged to acknowledge that England was a land with a strong sense of law, liberties and ancient customs.

Perhaps the most remarkable of all of the royal letters dispatched this week was superficially amongst the most routine. On 30 October, again from the Tower, the King wrote to one of his foreign constables, Thierry Teutonicus (literally 'Terry the Teuton').18 The terms of this letter deserve to be quoted in full:

'The King sends greetings to Thierry the Teuton. Know that, by God's grace, we are in good health and unharmed, and we order you to restore, as soon as you can, the horse that you borrowed from Richard the Fleming. We shall shortly be coming to your part of the country, and we shall be thinking of you, about the hawk, and though it might be ten years since we last saw you, at our coming it shall seem to us no less than three days. Take good care of the custody that we have entrusted to you, letting us know regularly of the condition of this custody. Witnessed by myself (the King), at the Tower of London, 30 October'

Is this, as it appears to be, a simple letter offering greetings and instructions about horses and hawks, or does it convey a rather more sinister message? By 3 November 1214, there is no doubt that Thierry the Teuton had a particularly delicate responsibility to discharge. On that day he was ordered to ensure safe passage for the Queen, Isabella of Angoulême, under armed escort supplied by Peter des Roches, via Freemantle and Reading to Berkhamsted, a castle that formed part of the Queen's dower.19 Thierry had served as constable of Berkhamsted from November 1213, itself perhaps an indication that he was already attached to the Queen's service.20 Certainly, after November 1214, he was to emerge as a leading member of the Queen's household.21 Isabella appears to have returned with the King from Poitou, earlier in October, staying initially at Exeter, another castle that formed part of her dower.22 If she were the 'custody' referred to in John's letters of 30 October, then the King's promise that 'though it might be ten years since we last saw you, at our coming it shall seem to us no less than three days' could be interpreted not so much as an expression of goodwill but as a veiled threat.

1 | RLP, 123. |

2 | C. Tilley, 'The Honour of Wallingford, 1066-1300', Unpublished PhD thesis, King's College London, 2011, available online at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/theses/the-honour-of-wallingford-10661300(9fa35434-f316-468a-9626-97b4cb4f9a4e).html, and cf. idem, 'Magna Carta and the Honour of Wallingford', Historical Research (forthcoming). |

3 | RLP, 122, and cf. the gift of wine for Robert, reported in RLC, i, 174b. |

4 | RLP, 122-2b. |

5 | RC, 202. |

6 | RLP, 123, and in general, N. C. Vincent, 'Jocelin of Wells: The Making of a Bishop in the Reign of King John', Jocelin of Wells, ed. R. Dunning (Woodbridge 2010), 9-33. |

7 | RLC, i, 176-6b. |

8 | RLC, i, 175. |

9 | RLC, 175b-6. |

10 | RLC, i, 176. |

11 | RLC, i, 175b. |

12 | RLC, 176. |

13 | RLC, i, 174b. |

14 | RC, 201b-2. |

15 | RC, 202. |

16 | Here relying on the two witness lists reported in RC, 202. |

17 | RC, 201b-2. |

18 | RLC, i, 175b. |

19 | RLC, i, 177. |

20 | RLP, 105b; RLC, i, 154b, 162b. |

21 | N. C. Vincent, 'Isabella of Angoulême: John's Jezebel', King John: New Interpretations, ed. S.D. Church (Woodbridge 1999), 165-219 |

22 | RLC, i, 433, an order of October 1220 to credit John of Lydford with the expense of three measures of wine that Eudo de Beauchamp received from him by order of King John and which were used in expensis predicti I(ohannis) regis patris nostri et I(sabelle) regine matris nostre in mora sua quam fecerunt apud Exon' in ultimo reditu ipsius I(ohannis) patris nostri et predicte regine matris nostre de Pictau(ia). |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)