John grants freedom of election

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

16-23 Nov 1214 |

RC, 202b-3, 204; RLP, 123-4b, 140b; RLC, i, 177b-8b, 179b, 181b; [New Charters, below] |

||

22-23 Nov 1214 |

RLC, i, 179b |

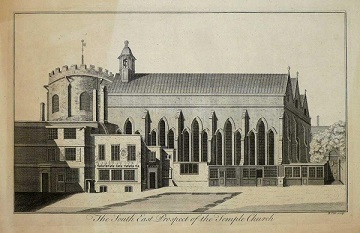

This was to prove an eventful week. Perhaps because the palace of Westminster was under repair, perhaps to emphasize his presence within the City whilst placing himself and those who came to negotiate with him under the neutral protection of the Templars, the King took up residence in the New Temple, south of Fleet Street. There he remained for the eight days from Sunday 16 to Sunday 23 November. The Temple precinct had first been used by him in 1212-13, at the time of the negotiations bringing the bishops out of exile. It was therefore already associated with hard-bargaining, several centuries before its transformation into a hive of lawyers and arbitration that it remains today. Here, on Friday and Saturday, 21 and 22 November 1214, deals were struck with the bishops claiming compensation from the time of the Interdict. The intention was clearly to rid the King of the far greater financial penalties to which he had been condemned during the previous year. At the same time, the bishops received immediate, rather than potential satisfaction. Only a selection of the charters granted on this occasion were copied onto the chancery charter roll.

The most important of these was the charter by which John recognized Stephen Langton and all future archbishops of Canterbury as patrons of the see of Rochester.1 The charter is stated specifically to have been made 'by the counsel of bishops, earls, barons and others of our faithful men'. This was a phrase subsequently echoed six months later in the preamble to Magna Carta, itself granted 'by the counsel' (per consilium) of a named group of bishops, earls, barons 'and others of our faithful men'. The archbishop, the Rochester charter promised, was to have custody of the see during all future vacancies, together with its temporalities (these 'temporalia', as the charter phrases it, no longer to be known as 'regalia'). All service owing from the see was to be rendered by Rochester to the archbishop and only then by the archbishop to the King. The bishops of Rochester were to swear fealty to the King as 'prince' (princeps) but not on account of any fee (non propter feodum). The charter ends with an elaborate sanctions clause, threatening the wrath of God, the Virgin Mary and all the saints against anyone infringing its terms; a clause that was surely added under the advice of Langton and his fellow bishops, but that nonetheless reveals the continuing potential of the King to act as mediator between God and his subjects.

The charter's witness list, in common with those of other charters issued on this occasion, includes not only royalists (Peter des Roches, the earls of Chester, Pembroke, Arundel, Warenne and Ferrers, in that particular order, William Brewer, Thomas of Erdington, and the chancellor, Richard Marsh) but various of the exiled bishops (William of London, Eustace of Ely, Giles of Hereford, Jocelin of Bath and Glastonbury, Hugh of Lincoln) and of at least four barons (Saher earl of Winchester, Robert fitz Walter, Geoffrey de Mandeville and Richard de Montfichet, not to mention here bishop Giles of Hereford) later amongst the twenty-five chief rebels of Magna Carta. The future rebels, it is worth noticing, witness the charters of privilege to the Church but not all other charters issued on the same occasion.2 This may or may not suggest that they attended the New Temple meeting as adherents of Langton and the bishops, rather than as regular members of the King's court.

Again on the charter roll, although not copied there until mid January, we find the King's charter to Hugh bishop of Lincoln, dated 21 November, specifically offered 'in recompense for the seizures, injuries and damages .... made in the time of the general Interdict'. Here, bishop Hugh was promised the manor of Winthorpe near Newark, thirty years earlier mortgaged to Aaron the Jew (of Lincoln) and seized after Aaron's death (in 1186) by King Henry II. The bishop and his successors were also quit an annual rent of £10 for the wapentake (or county division) of Stowe. They were granted permission to enclose and construct hunting parks at five named places free from interference by the King's foresters, license to divert the road leading from Kimbolton to Huntingdon through what previously been royal forest, and further license to establish annual fairs and weekly markets at all of their demesne manors, save when this damaged neighbouring markets.3 A few days, Hugh was given 100 stags and hinds by the King, presumably to stock his new parks.4

Beyond the official charter roll, further charters issued on 21-22 November are known from copies in cartulary or other local sources. Here we find that on 21 November, bishop Jocelin of Wells was promised continued enjoyment of the patronage (and part of the revenues) of the abbey of Glastonbury.5 Archbishop Langton was confirmed in the estate of seven knights' fees that Robert de Meinil had once held from William Painel and that William had confirmed to archbishop Hubert Walter in the late 1190s.6 The Meinil fees lay in Yorkshire, the most distant of all the archbishop of Canterbury's English estates. Earlier in the reign, John seems to have granted them, together with the Meinil heir, to the courtier Robert of Thurnham, whose chief inheritance had in due course passed to the alien Peter de Maulay. They were now definitively restored to Langton.7 Hugh of Lincoln was further granted pardon of up to 600 marks of debt.8 The bishop of Ely was promised rights of free chase in the forest of Huntingdon, and the patronage of Thorney Abbey with appointment of abbots at each new vacancy and fealty from the abbot-elect for the abbey's temporalities (here, as in the Rochester charter to Langton, 'formerly known as regalia'), ending with a sanctions clause threatening the vengeance of God, the Virgin Mary and all saints against any infringements of these terms.9 The bishop of London was granted the manor of Stoke by Guildford in Surrey.10 Writs copied in the Patent and Close Rolls command the enforcement of these gifts by local officials. They also record further concessions: a pardon to the bishop of Ely of a loan of £100 made when he had served as ambassador into Normandy over the Interdict, the release of a clerk to the bishop of London previously held in the Fleet prison for pleading a lay fee in court Christian, the rebuilding of the bishop of London's castle at Bishop's Stortford, destroyed during the Interdict, and an enquiry into recent attacks upon the bishop's manor of Stepney (Stebeh').11 In addition, Master Simon Langton, the archbishop's brother, was granted the right to enclose all land pertaining to his prebend of Strensall in York Minster, 'just as others of those parts enclose their "gwaynagia"'. This writ employs a technical term 'waynagium' (a Latin translation of 'gagnage', both the profit of land and the means of taking such profit) that itself in due course was to reappear in Magna Carta clause 20.12

Following this great release of gifts, on 22 November, the King wrote separately to the religious of the diocese of Ely, both monks and clerks, asking that, as a matter of grace, they cease from demanding the repayment of goods taken from them during the Interdict, which goods 'are now called "seizures" (ablata)'.13 Similar requests were sent on 24 November to the archdeaconries of the diocese of Lincoln, and a week later, to the prior and monks of Bury St Edmunds, followed in the Patent Roll by a blank form enabling an unspecified monastery to declare itself entirely satisfied over all debts owing by the King since the time that the Interdict was first enforced.14 In all probability, similar letters were sought from other monasteries and dioceses. Just such 'blank' charters had earlier been extorted from English monasteries, by the chancellor Richard Marsh, in the process incurring widespread scandal.15

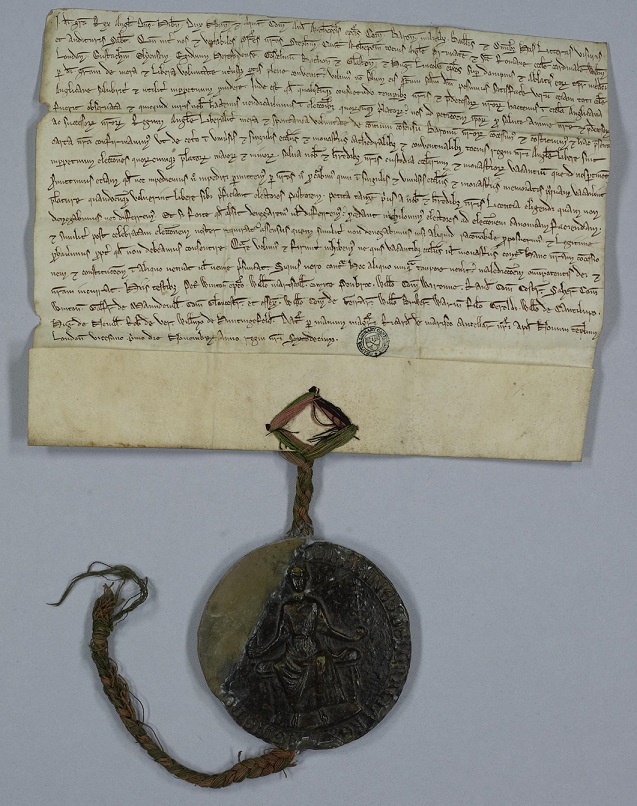

The grants made to individual bishops and clergy on 21-22 November were far from negligible. Some (as with the charters concerning the patronage of Glastonbury, Thorney and Rochester) had longstanding consequences for monastic communities that had previously enjoyed protection from the King.16 In return for their new privileges, the bishops tacitly abandoned all further right to the much larger sums that they had originally demanded in compensation. This is explained by the King's financial incapacity and by his grant, on 21 November, of a far more general concession to the English Church. This, the so-called 'charter of free elections', already anticipated by disputes earlier in November 1214 at Bury St Edmund's and Rochester, forms the subject of a study by Katherine Harvey elsewhere on this website. For present purposes, it is important that we begin by noting that the charter itself was not enrolled on the official chancery charter roll. There, unlike the charter to the bishop of Ely concerning Thorney or to the bishop of Bath concerning Glastonbury, it is not even known from its reissue, later in January 1215.17 Whether this reflects a deliberate decision by the chancery clerks to suppress any record of this and other charters remains unclear. The charter of 21 November survives only because it was preserved by the monks of Canterbury both as an original and in cartulary copies. As Christopher Cheney long ago demonstrated, the opening of the charter borrows directly from the papal letters of April-May 1214, laying down financial conditions for the raising of the Interdict but allowing that some other settlement might be devised 'with the full and free will of both parties'.18

The charter itself (as Cheney, Richardson and Sayles, and most recently Katherine Harvey have all pointed out) is as remarkable for what it omits as what it includes.19 Offered to the archbishop and to the bishops of London, Ely, Hereford, Bath and Lincoln, and referring specifically to the damages and seizures inflicted upon them during the Interdict, it undertakes that 'whatever the custom previously observed in the English Church in our time and that of our predecessors, and whatever right <the King has> previously claimed in the election of any prelates', the King, with the consent of his barons, now grants that 'elections are to be free in perpetuity in every and each cathedral or conventual church or monastery'. The custody of vacant churches was nonetheless reserved to the King and his successors, as was the right to demand that the electing bodies first seek licence to elect. Albeit that the King 'will neither deny nor delay' such licence (non denegabimus nec differremus - words that directly prefigure those of Magna Carta clause 39, promising that the King will neither deny nor delay, nulli negabimus aut differemus, justice). Should the King fail to grant licence, the electors might proceed regardless to a canonical election. After election, the King's assent was to be sought, again without denial unless the King could show any legitimate reason why he should not consent. Once again, as with other charters of this date, the charter ends with a sanctions clause, but in this instance promising the curse of 'God almighty and of us ourselves'. Fourteen witnesses are named, including three future members of the baronial twenty-five (Saher earl of Winchester, Geoffrey de Mandeville here granted title as earl of Gloucester and Essex, and William of Huntingfield).

Superficially, this was very much what the English bishops had been seeking for a year or more. In practice, not only did the King specifically stake his claim to regalian right during vacancies, but by reserving his authority to license elections and refuse consent to elections that he considered illegitimate, retained considerable leverage over electoral process. There was no formal rejection here of the tradition of elections taking place in the King's chapel, and no formal prohibition against the King expressing his favour for a particular candidate, either in person or by sending his proxies to inform the electors. Moreover, although the charter at no point specifically refers to either the Pope or the papal legate, Nicholas of Tusculum, there can be little doubt that the Pope stood high amongst its intended audience. Here, King John borrowed a technique of public advertisement of his willingness to obey the canonical customs of the Church, already to be found in similar charters of free election issued by the rulers of Aragon, Sicily, Austria and the Empire.20 On 18 November, three days before issuing his charter, John had paved the way here by appointing an embassy to represent him in Rome.21 Comprising the royalist abbot of Beaulieu, the Templar Alan Martel, the royal official Thomas of Erdington, and the Roman clerk Peter Saracen, this embassy did not in fact set out until the spring of 1215. However, when it did eventually materialize, its arrival in Rome coincided unerringly with the Pope's confirmation of John's charter of free elections. In other words, far from attempting to suppress the charter, John hoped to use it to win further papal support.22

The King's real attitude is better revealed in the election of the new abbot of St Albans, signalled on 18 November, when Thomas de Neville, the King's local official, was instructed to find horses for ten St Albans' monks making their way to the King's presence in the New Temple.23 It was in the Temple, quite possibly with the King as spectator, that on 20 November (the feast of St Edmund) the monks elected their new abbot, William of Trumpington. The fact that this election was held at court goes unmentioned in Matthew Paris's account of events. Paris does nonetheless record a speech that the King is reported to have made when the monks presented their candidate. The King enquired the name of the abbot elect. Learning that it was William of Trumpington, 'Aha!', the King exclaimed, 'It was precisely him that I wanted! You have elected him wisely, and have thereby avoided frustrating us. He is brother to that most trustworthy (discretissimus) knight, William of Trumpington, in whose footsteps he will surely follow'. The King then gladly received the new abbot with a kiss of peace. Matthew Paris, writing in the 1230s or later, comments that this proved that William's election had not been conducted purely in accordance with God's laws.24 In fact, what this vignette suggests is the great gulf that continued to divide precept from practice.

A further factor in these calculations was the position of the Pope's legate in England. Attacked after his arrival in 1213 for his over-enthusiastic backing of royal candidates and for thwarting the wishes of Langton and the other bishops, the legate Nicholas had by the autumn of 1214 so identified himself with the cause of King John that papal letters were sought, ordering his withdrawal from England. This recall was perhaps negotiated by the archbishop's brother, Master Simon Langton. Simon is heard of in Rome, in the summer of 1214, and next at Rochester, where in early December he took part in the promotion as bishop of Langton's former pupil, Benedict of Sawston, at that time still teaching in the schools of Paris.25 Meanwhile, the details of Nicholas's departure can be reconstructed only in outline. On 26 November, the bishop of Winchester sent 50 marks 'after the legate', who himself can be found at Rochester, on 27 November, issuing letters on the forthcoming election in accordance with a papal letter of 13 September. 26 This in turn suggests that the legate's recall was issued after 13 September. As early as 16 November, nonetheless, various of the legate's servants were preparing to depart from Dover.27 On 17 November, the King granted protection to Master John of Caen, rector of Cheshunt, from other sources known to have been the legate's clerk.28 On 2 December, the legate issued an indulgence following his consecration of altars in St Martin's Priory at Dover, suggesting that he himself crossed overseas at about this time.29

At the London council of November, King John was clearly keen to obtain favour with others of the cardinals, on 18 November writing to them to ask for their continued assistance.30 A number of pensions were paid from the Exchequer, to cardinals including the future legate Guala, the bishop of Ostia, and to at least two kinsmen of the Pope, including the Pope's brother, 'count' Richard. Most significantly, on or after 28 November the papal census first agreed in 1213 was paid up to the term owing at Michaelmas 1214.31 All of this, taken together with the charter of free elections, suggests a carefully orchestrated campaign of propaganda targetted at Rome. On 20 November, again clearly in the expectation that this would buy him friends in the papal court, the King issued solemn letters commanding his seneschal in Gascony to put down the 'the detestable perfidy of the heretics'. These letters employ the full range of Roman vocabulary, demanding that the heretics of southern France face 'extirpation' following 'enquiry' or 'inquisition' (inquiratis .... extirpare).32 On 21 November, a clerk of the cardinal bishop of Ostia was presented by the King to a church in the diocese of London.33

It was not only ecclesiastical affairs that continued to preoccupy the King. On 22 November, he granted a charter to Margaret, the widow of Robert fitz Roger, confirming her inheritance both from her father and her husband. Clauses here specifically excused her from interest on the Jewish debts of her father, forbade that she be married against her will and promised her dower 'in accordance with the custom of our realm of England', all of these being privileges of widowhood later recognized in Magna Carta. From Margaret's inheritance, the King held back Norwich castle, once the possession of her father, William de Chesney, lord of Blythburgh, more recently held by her husband, lord of Warkworth and Clavering, in his capacity as sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk for much of the decade from 1190 to 1200.34 The charter was witnessed by an exclusively lay assembly, including the earls of Pembroke, Chester, Warenne, Arundel, Ferrers, Winchester, Robert fitz Walter and William de Aubigny of Belvoir, these last three later prominent amongst the baronial twenty-five. What this confirms is the exceptionally solemn nature of the New Temple assembly, attended by both bishops and barons.

There is also evidence during this week for continued military preparations by the King. On 18 November, a major enquiry was ordered into all heavy shipping, foreign or otherwise, then in English ports, the results to be sent to the King before Christmas.35 The most likely explanation for this is that the King continued to fear a French invasion. On 20 November, Stephen Harengod replaced Matthew Mantel as constable of Colchester, and repairs were effected to the castle.36 Nuncios were entertained from the Emperor Otto, still smarting from his defeat at Bouvines.37 The King's wardrobe was at last brought from Winchester to London, and preparations were made for the purchase of robes, in Bury St Edmunds, York and Lincoln, towards the King's coming Christmas festivities.38 The man appointed to oversee this, Reginald of Cornhill, was a prominent London businessman closely attached to the royal court, since 1213 serving simultaneously as constable of Rochester Castle. He had recently been confirmed as constable by archbishop Langton.39 It was in due course Reginald's refusal or inability to surrender Rochester Castle to the King that was to mark a crucial stage in the civil war of 1215. On the same day that he issued his charter of free elections, the King also sent instructions north, for the construction of siege catapults, mangonels and petraries at Nottingham castle and elsewhere. At Corfe, the moat was to be improved.40

1 | RC, 202b, with several further copies preserved in Canterbury or Rochester sources, and cf. RLC, i, 179, orders to the keepers of the bishopric to grant Langton all receipts taken since the death of bishop Gilbert. |

2 | For example, not the charter to Cîteaux, of 22 November 1214: RC, 202-202b |

3 | RC, 203b-204, also surviving as an original, Lincoln, Lincolnshire Archives D. & C. Lincoln A1/1B/44a. whence The Registrum Antiquissimum of the Cathedral Church of Lincoln, ed. C.W. Foster (vols. 1-4) and Kathleen Major (vols. 4-10), 12 vols. (Hereford, 1931-73), i, no.206, and for enforcement cf. RLC, i, 179b. |

4 | RLC, i, 179b. |

5 | Adami de Domerham Historia de rebus gestis Glastoniensibus, ed. T. Hearne, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1727), i, 238; Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Dean and Chapter of Wells, 2 vols., ed. W.H.B. Bird and W. Paley Baildon, Historical Manuscripts Commission (London, 1907-14), i, 310-11 |

6 | London, Lambeth Palace Library ms. 1212 (Archbishopric cartulary) fos.12v and 27r (13v, p.22 and 14r p.49, misbound) no.25, fos.105v-106r (92v-93r, pp.203-4), whence Early Yorkshire Charters: VI, The Paynel Fee, ed. C.T. Clay (Wakefield, 1939), 189 no.89. |

7 | See here CRR, viii, 45; Early Yorkshire Charters VI, 185-9; F.R.H. Du Boulay, The Lordship of Canterbury: An Essay on Medieval Society (London, 1966), 90. |

8 | Calendar of Charter Rolls 1327-41, 147 no.43. |

9 | TNA C 47/12/8 (Cartae Antiquae Roll NN) no.28; Oxford, Bodleian Library ms. Laud Misc. 647 (Liber Eliensis) fo.122v-123r (39v-40r), and cf. RLC, i, 179b. |

10 | Calendar of Charter Rolls 1226-57, 153-4; Cartae Antiquae Rolls, i, 4 no.11; Early Charters of St Paul's, 37-40 nos.52-3. |

11 | RLP, 123b-4; RLC, i, 178. The destruction of the castle at Stortford (perhaps the present ruin of a motte and bailey castle known as 'Waytemore Castle) is mentioned in an unpublished continuation of the chronicle of Ralph Niger, derived from lost portions of the chronicle of Ralph of Coggeshall, here apparently associated with the building of the King's new house at Writtle, c.1210: BL ms. Royal 13.A.xii fo.39r ('Castrum Lond' episcopi, scilicet Stoteford euertitur. Domus regis apud Writel' edificatur'). |

12 | RLP, 124; RLC, i, 178b. For 'waynagium', see J. Tait, 'Studies in Magna Carta', English Historical Review, xxvii (1912), 720-8. |

13 | RLP, 140b. |

14 | RLP, 124, 140b |

15 | Two Cartularies of the Priory of St Peter at Bath, ed. W. Hunt, Somerset Record Society vii (1893), part i, p.18 no.82; Chronicle of the Election of Hugh abbot of Bury St Edmunds, ed. Thomson, 134-46. |

16 | For Rochester, in general, C. Flight, The Bishops and Monks of Rochester, 1075-1214 (Maidstone. 1997); for Glastonbury, Jocelin of Wells: Bishop, Builder, Courtier, ed. R. Dunning (Woodbridge, 2010); for Thorney, The Letters and Charters of Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, Papal Legate in England 1216-1218, ed. N. Vincent, Canterbury and York Society 83 (1996), no.158, claiming that bishop Eustace of Ely first showed his charter to the monks of Thorney at Stanground, near Peterborough, on 13 December 1214, being immediately contradicted by the abbot and monks. |

17 | RC, 203b-204b, for the charters to Ely and Bath. For the King's reissue of the charter of free election, dated 15 January 1215, see Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 126-7, taken from the papal confirmation of 30 March 1215, itself surviving there in a notarial copy of 1305, now TNA SC 7/19/17. |

18 | F.M. Powicke and C.R. Cheney, eds., Councils and Synods 1205-1313, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1964), i, 39. |

19 | Cheney, in Councils and Syndods, 39; H.G. Richardson and G.O. Sayles, The Governance of Medieval England (Edinburgh 1963), 381; K. Harvey, Episcopal Appointments in England, c.1214-1344: From Episcopal Election to Papal Provision (Farnham, 2014), 13-28. For the charter itself, printed from Canterbury Cathedral Archives Chartae Antiquae C109, see Councils and Synods, i, 40-1. |

20 | Harvey, Episcopal Appointments, 22. |

21 | RLP, 123b. |

22 | C. R. Cheney, Pope Innocent III and England, Päpste und Papsttum 9 (Stuttgart, 1976), 365 n.45, citing RC, 202b, 204b; Matthaei Parisiensis, Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard, 7 vols. (Rolls series, 1872–83), ii, 606-7, here following the analysis by Harvey. |

23 | RLC, i, 177b. |

24 | Matthew Paris, 'Gesta Abbatum', in Chronica Monasterii S. Albani, ed. H.T. Riley, 7 vols. (London, 1863-76), 4 part 1, 254. |

25 | RC, 208b-9; Paris, Chronica Majora, ii, 571-2, 574, and for events at Rochester, H. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, 2 vols. (London 1691), i, 385-6. |

26 | For the 50 marks, see RLC, i, 180. At Rochester, Nicholas published papal letters of 13 September 1214, ordering him to assist in a canonical election to the bishopric: BL ms. Cotton Domitian A x (Rochester cartulary) fo.193r (191r), also in London, Lambeth Palace Library ms. Register of Archbishop Islip fo.224r, where the legate's letter is followed by a narrative account of the election of bishop Benedict at Rochester, printed variously as The Letters of Innocent III, 1198-1216, Concerning England and Wales, ed. C.R. and M.G. Cheney (Oxford, 1967), no.978; Wharton, Anglia Sacra,i, 385; Registrum Roffense, ed. J. Thorpe (London 1769), 55. Cheney (Innocent III and England, 364 n.39) refers to letters of the legate issued at St Albans on 16 November, but these are in fact dated 16 kalends January, i.e. 17 December, probably in 1213 rather than 1214: Westminster Abbey Muniments 3779, whence F.T. Wethered, St Mary's Hurley in the Middle Ages (London, 1898), 105 no.45. |

27 | RLC, i, 181b. As noted by Cheney, in Councils and Synods, i, 21n., Matthew Paris' 'Gesta Abbatum' of St Albans claims that the legate Nicholas was still in a position to visit St Albans more than a month after the blessing of abbot William, elected on 20 November and blessed by the bishop of Ely on 30 November 1214. Here, Paris perhaps misattributed to the legate Nicholas an encounter better associated with the legate Guala, himself reported in the 'Gesta' as visiting St Albans before November 1214. In reality Guala did not arrive in England until May 1216, more than eighteen months later; cf. Matthew Paris, 'Gesta Abbatum', 4 part 1, 252-7. Alternatively and more plausibly, Paris' claim ('Gesta', ed. Riley, i, 257) that the legate Nicholas was a Cistercian monk may demonstrate confusion between Nicholas de Romanis, cardinal bishop of Tusculum (1204-1218/19), legate in 1213-14, and the papal penitentiary, Nicholas of Clairmont, undoubtedly a Cistercian monk, cardinal bishop of Tusculum from the death of Nicholas de Romanis until his own death in 1227, himself active in peace negotiations in England in 1217: Letters of the Legate Guala, ed. Vincent, no.142n. |

28 | RLP, 123-3b; Letters of the Legate Guala, ed. Vincent, no.140, and cf. the legate's steward, Mailes of Amiens, recorded in RLC, i, 180. |

29 | London, Lambeth Palace Library ms. 241 (Dover cartulary) fo.53v. |

30 | RLP, 123b. |

31 | All of these payments known from the long writ of liberate, RLC, i, 179b-180. |

32 | RLP, 124. |

33 | RLP, 123b. |

34 | RC, 203, where the charter is dated at the New Temple on 22 December, although clearly of November rather than December. For Margaret's inheritance, see see I. J. Sanders, English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086-1327 (Oxford, 1960), 16. |

35 | RLC, i, 177b-178. |

36 | RLP, 123b; RLC, i, 180. |

37 | RLC, i, 177b, 180, and cf. p.178, ordering the release of a man arrested for carrying imperial letters requesting the restoration of his estate. |

38 | RLC, i, 177b. |

39 | London, Lambeth Palace Library ms. 1212 (Archbishopric cartulary) fo.13r (p.23), covering Reginald's appointment as constable in August 1213 and the renewal to a fortnight after Easter 1215, negotiated with Langton's steward, Master Elias of Dereham, on 17 August 1214, whence the study by I.F. Rowlands, 'King John, Stephen Langton and Rochester Castle, 1213-15', Studies in Medieval History Presented to R. Allen Brown, ed. C. Harper-Bill and others (Woodbridge, 1989), 267-280. |

40 | RLC, i, 178-178b. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)