John prepares his exfil

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

28 June 1215 - 4 July 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

27-30 Jun 1215 |

RC, 210; RLP, 145b-6; RLC, i, 217b-18 |

After the flurry of commands in the previous week intended to redress ancient injuries, the pace of political accommodation between King and barons slowed. William de Harcourt was commanded to release Mountsorrel castle to Saher de Quincy, and a prisoner held at Eye in Suffolk was ordered restored to Robert fitz Walter.1 Giles de Braose, bishop of Hereford, was invited to court, the letters of invitation here being deliberately altered so as to appear less peremptory.2 Men of the bishops of Salisbury and Bath, arrested apparently on suspicion of trespass in the King's forest, were ordered released.3 Henry de Braybeuf was promised the restoration of the dower of his wife in Oxfordshire, previously seized by the King 'without judgment' ('sine iudicio')4, and there was a further reminder to the constable of Berkhamsted that Ralph Chenduit, deprived of land by the King, was to be restored to possession.5 Peter de Maulay, one of the King's alien favourites, was ordered to restore the Wiltshire manors of Corsham and Stratton to their rightful owner, Robert de Cresek, retaining nothing for himself save his standing corn.6 Another alien, Geoffrey de Martigny, in theory dismissed from office under the terms of Magna Carta clause 50, was reminded of his orders to release Northampton Castle to Roger de Neville. Even so, there was sugar to this pill. Geoffrey was told to come to the King as a favoured servant, with his garrison and munitions, leaving no weapons in the castle save for two crossbows of horn and others of wood.7 At the request of Archbishop Langton, a prisoner, William the reeve, was released from captivity at Dover.8 Hubert de Burgh was granted custody of the honour of Peverel, of the chamberlainship and exchange of London, and received further letters instructing the King's men at Dover to ensure him custody of Dover Castle.9 Similar reminders were sent to Yorkshire, commanding the surrender of the sheriffdom and the castles of Pickering and Scarborough to William of Duston, whilst the counties of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire were instructed to answer to Ralph Hareng as sheriff.10

Subsequent evidence suggests that it was also during this week, on 29 June, that terms were at last agreed by which Walter de Lacy might recover his lands in Ireland, in return for a fine of 4000 marks payable by Michaelmas 1216 and the temporary surrender of his castle and estate at Drogheda. The terms of this settlement are interesting not least for what they suggest was still the King's keen determination to embark (or at least to declare his intention of embarking) upon a crusade expected to last for at least three and possibly for as long as five years. However, although negotiated in late June, the fine itself and Walter's restoration were not properly implemented until the end of July: an indication, perhaps, of the ways in which the King was accustomed to using delaying tactics as a means of securing obedience. Walter's fine also contained clauses promising the release of his son as hostage, and even after the payment of the money owing, undertaking that the King might take another son or daughter as hostage.11 Despite the unpopularity of such hostage-taking it seems that the King's habits remained unaltered.

Although there are indications this week that the Exchequer had been re-established, almost certainly at Winchester, ready cash remained in short supply.12 Hence the continued flow of jewels and treasure to the King, previously entrusted to the keeping of the abbots of Bindon, Stanley and Burton and the prior of Bradenstoke.13 At Marlborough, the King raided his own stores of cash and plate, taking away 60 marks in coin and more than 50 silver cups.14 Shortage of cash perhaps helps to explain the emphasis this week upon Irish business, with the negotiation of substantial fines from a series of Irish barons for privileges or land. Thus the counties and towns of Waterford and Cork were entrusted to Thomas fitz Anthony, who fined 100 marks a year over the next six years for custody and the land and heir of Thomas fitz Maurice.15 The men of Dublin received a new charter and their city at an annual fee farm of 200 marks.16 The burgesses of Dungarvan, near Waterford, were granted privileges according to the customs of Breteuil.17 Prisoners taken as long ago as 1210 at Carrickfergus continued to fine for release.18 Various of the charters to Irish beneficiaries reveal the presence at court of Irish barons (the archbishop of Dublin, the bishop of Emly, William Marshal, Geoffrey de Marisco, Roger Pipard, Ralph Parvus, Walter of Riddlesford, Philip of Worcester and Geoffrey Lutterell).19

Even so, the Irish business transacted here, as in weeks to come, suggests something rather more than a mere hunger for coin. John had first grown to political maturity in Ireland. Here, at the crisis point of his reign, he may have turned once again to Ireland, not least as a potential refuge from the chaos with which England was engulfed. Although the announcement was delayed until the following week, it was almost certainly at this time that arrangements were made for Geoffrey de Marisco to succeed Archbishop Henry of Dublin as Irish justiciar.20 These arrangements coincided with a similar rearrangement in Gascony, where (on 29 June) it was announced that Geoffrey de Neville was to succeed Hubert de Burgh as seneschal of Poitou.21 Just as the King extended new privileges to the men of Dublin and Dungarvan, so (on 4 July) the men of Cognac were promised the right to a commune and the election of a mayor.22 In Ireland, not only were fines negotiated, but on 30 June, Thomas of Galloway was promised the castle of Antrim as part of his new settlement in Ulster .23 As part of a wider settlement of affairs in the far west, and against the threat of hostilities from the native Irish of Connaught, guarantees were issued to anybody receiving land in the 40 cantreds of Limerick previously assigned, and the justiciar in Ireland was commanded to warn all living on the frontier between the King's lands and those of the native Irish that they were to place the Marches under proper protection by Michaelmas (29 September) on pain of confiscation and the reassignment of their estates.24

Coinciding with these arrangements for Ireland, we find the King taking a pronounced interest in maritime affairs. Besides what seem to have been routine grants of protection to foreign merchants visiting England25, instructions over wine and salt were sent to the men of Winchelsea.26 The men of Hastings received favours, including recognition of their right to hold court at Yarmouth.27 Ships of Yarmouth arrested at Winchelsea were to be released into the King's service and taken to Southampton and William de Neville and the constable of Portchester were commanded to find equipment for at least eleven ships at Portsmouth and elsewhere, to be supplied with keys, likewise going into royal service ('iture in seruicium nostrum') at the King's expense.28 Winchelsea supplied at least eight vessels for this fleet, with crews paid for from the Exchequer.29 The merchants of Rouen, meanwhile, were promised freedom from all maltolts on their wine traded at Southampton.30

As to the purpose of the King's fleet, various possibilities arise. Most likely, given its south-coast focus, it was intended to spy upon French shipping in the Channel and give early warning of any projected Capetian attack. A more exotic explanation would be that the King was preparing an escape route for himself. Should English politics sour even further, he perhaps contemplated bolting for Poitou.31 Roger of Wendover, to some extent supported by Walter of Coventry, declares that in the aftermath of Runnymede, the King turned pirate and set to sea along the English south coast. As we shall see, this improbable story perhaps incorporates elements of truth, albeit of truth as enacted in late August 1215 rather than early July. Even so, the ships mustered in July may well have included those with which the King sought to operate six or seven weeks later.32 As for political negotiations themselves, the next established milestone had been set in mid June, with provision for 15 August to serve as a term for the King's redress of grievances and the rebel surrender of London. Meanwhile, we have evidence as early as 29 June that an interim meeting had been convened for Oxford in mid July, with commands to the sheriff of Berkshire to supply wine to the King's houses at Oxford, there to await the King's coming.33

1 | RLP, 145b-6. |

2 | RLP, 146. |

3 | RLP, 145b; RLC, i, 217b. |

4 | RLC, i, 218, apparently relating to land at Headington and Oxford. Henry was subsequently a leading member of the household of William Marshal the younger, at this time himself either close to, or a member of the rebel camp. His wife, Clementia, was the widow in turn of Alan de Plugenet, and Wandregil de Curcellis, for whom Henry had fined 4 palfreys in 1214 (Pipe Roll 16 John, 132). Despite her exclusion from the listings of Stephen's five other daughters (cf. Pipe Roll 6 Henry III, 64) she was undoubtedly a daughter and coheiress of the royal official, Stephen of Thurnham (d.1214) with claims to land at Artington and Peperharrow (Surrey) and Frome (Somerset), for which see CRR, vii, 277, 319, viii, 362-3. Her exclusion from the usual listings of Stephen's heiresses might suggest that she was born to an early marriage by Stephen, before his marriage to the heiress Edelina de Broc. |

5 | RLC, i, 219, and cf. RLC, i, 216. |

6 | RLC, i, 218. |

7 | RLP, 146b; RLC, i, 218-18b, and cf. RLC, i, 218b, where Roger de Neville was granted land to sustain him as sheriff. |

8 | RLC, i, 218b. |

9 | RLP, 145b-6. |

10 | RLP, 146b, and cf. RLC, i, 218 for commands that William of Duston's expenses on the Tower of London be audited and that he be allowed to assart his wood at 'Banecroft'. |

11 | For the fine itself, sealed by Walter de Lacy, the archbishop of Dublin and the earl of Salisbury, containing two references to the feast of St Peter and Paul (29 June), RLP, 181-1b; Rot.Ob., 562-4, 601-3, and for this same feast subsequently considered as the date of the settlement, RLC, i, 224. |

12 | For orders to the barons of the Exchequer, or commands for accounts or enrolment there, see RLC, i, 217b-19. |

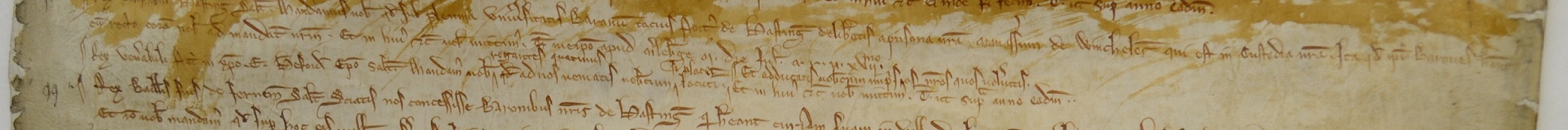

13 | RLP, 146-7, all of these receipts specifically referring to payments into the 'camera regis'. That for the monks of Burton survives as a mangled original: Stafford, Staffordshire Record Office D(W)1734/J/1809. |

14 | RLP, 147. |

15 | RC, 210b; RLP, 147. |

16 | RC, 210b-211, in return for a fine of 300 marks: Rot.Ob., 561-2. |

17 | RC, 211, repeated at 211-11b, and for the borough customs of Breteuil, particularly favoured as a model in the Welsh Marches, see M. Bateson, 'The Laws of Breteuil', English Historical Review, xv (1900), 302-18, 496-523, 754-7, xvi (1901), 92-110, 332-45. |

18 | RLP, 146b. |

19 | RC, 210b-11. |

20 | Geoffrey's appointment was officially notified to Ireland on 6 July (RLP, 148). However, Geoffrey, who already appears with title as justiciar in charters issued on 5 July (RC, 211b-12b) was being treated as justiciar as early as 3 July: RLP, 146b; Rot.Ob., 555. |

21 | RLP, 145b. |

22 | RLP, 147. |

23 | RLP, 146. |

24 | RC, 211, and cf. RLC, i, 218b, this latter being part of a series of commands to the justiciar in Ireland. |

25 | RLP, 146, for James le Sage of Ypres, and cf. RLP, 146b, for Jocelin Ruptarius and his ship. |

26 | RLP, 145b. |

27 | RLP, 146-6b. |

28 | RLC, i, 217b-18. |

29 | RLC, i, 218. |

30 | RLC, i, 217b. No specific quittance from maltolts is recorded in John's charter to the men of Rouen, issued in the interregnum before his accession as King, on 21 May 1199, which nonetheless contains detailed provisions on the rights of Rouen merchants trading wine at London and elsewhere: J.H. Round, Calendar of Documents in France illustrative of the History of Great Britain and Ireland (London, 1899), no.112, with a proper edition forthcoming as part of the British Academy's Angevin Acta Project. |

31 | The focus here upon Southampton and Portsmouth rather than Bristol and the West seems to rule out Ireland as a potential place of refuge. |

32 | See King John's Diary and Itinerary 23-29 August. |

33 | RLC, i, 218. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)