John's dealings in Ireland

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

1 February 1215 - 7 February 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

1 Feb 1215 |

RLP, 127b; RLC, i, 185b |

||

1-3 Feb 1215 |

RLP, 127b; RLC, i, 185b, 186-6b |

RLC, i, 185b carries a writ misdated to Corfe on 1 January (recte February). |

|

4 Feb 1215 |

RLC, i, 186b |

||

5 Feb 1215 |

RLC, i, 186b |

||

6 Feb 1215 |

RLP, 128; RLC, i, 186b |

||

7 Feb 1215 |

RC, 205; RLC, i, 187 |

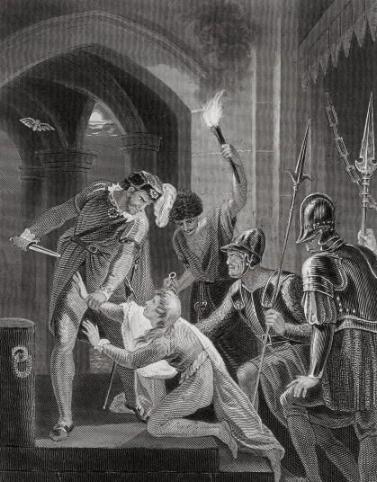

The King spent most of this week on the northern and western edges of Poole harbour, perhaps awaiting the arrival of mercenary reinforcements from France. He then travelled north to Marlborough in Wiltshire. There on 7 February he issued the week's only charter: a grant of a market and annual fair to Walter de Dunstanville, for his Wiltshire manor of Heytesbury. The witnesses to this charter, headed by the constable of Marlborough, Hugh de Neville, suggest a court attended by a fairly humble collection of knights. Amongst them, it is worth noting the presence of Henry fitz Count, bastard son of the late earl of Cornwall: a would-be great man in his own right, but here listed seventh in the witness list, behind such relatively minor figures as Henry fitz Aucher or Peter Escudemore.1 Earlier in the week, there had been a grant, by letters patent rather than by charter, of a weekly market to the men of Corfe, living in the shadow of John's great state prison, Corfe Castle.2 Peter de Maulay, Corfe's constable, was himself a figure of ill-omen, an alien from the Loire, exiled to England after the loss of John's northern French lands in 1204, and established by marriage as a major landholder in Yorkshire. Rumour still circulated that it was Peter, in 1202, who had carried out the murder of Arthur of Brittany, King John's young nephew: the event that more than any other had precipitated the loss of Normandy and hence the King's subsequent travails.3 On 1 February, Peter was granted letters of protection for himself, his men and his lands for so long as she should remain in service with horses and arms.4

The most significant business recorded this week concerned Ireland. On 1-2 February, the King issued a whole series of instructions relating to his Irish lands, most of them transmitted to Henry of London, archbishop of Dublin, newly appointed as successor to John de Gray, bishop of Norwich, as the King's chief minister in the province. The King of Connaught and his men were promised peace for so long as they remained faithful.5 Others of the Irish kings were sent gifts of scarlet cloth.6 Messages passed to Ireland via Amfredus de Dene and the archdeacon of Poitiers.7 The archdeacon, we can assume, was a refugee, now persona non grata in France as a result of his support for John's expedition of 1214.8 Amfredus, besides acting as go-between, was himself an active participant in the Irish land market, offering 100 marks for an Irish heiress (provided her childhood marriage could be dissolved), and during his time in England offering a further 500 marks for wardship of the lands and heirs of two further Irish barons, Richard de Tuith and Robert de Lacy. The fine was to be paid within a year, supplying some indication of the King's craving for cash. 9

The Archbishop of Dublin, meanwhile, was sent a long list of memoranda and instructions, mostly involving debts owed by Irish landowners, or new fines to be negotiated, in several instances for the release of hostages or prisoners.10 Various of these involved men, or the heirs of men who had first risen to prominence in Ireland during John's years as lord of Ireland, in the fifteen years prior to his accession as King in 1199. All told, nearly thirty individual transactions are detailed here, ranging from fines of 20 or 40 marks for the release of hostages, all the way up to far more substantial sums, such as the 1000 marks offered for four cantreds of land formerly held by the bishop of Norwich or the further 1000 marks offered for the wardship and marriage of the heir of Thomas fitz Maurice, son of Maurice fitz Gerald, himself one of the great figures of the conquest of Ireland fifty years before. These fines deserve more detailed treatment than they have previously been afforded. They go unremarked, for example, in Goddard Henry Orpen's detailed history of Ireland under the Normans.11 Taken collectively, they supply a snapshot of John's financial dealings in Ireland second in importance only to the Irish Pipe Roll for the year 1211-12 (14 John).12 Certain characteristics are worth highlighting here.

Firstly, there were the considerable profits that Ireland still promised to the crown. The total of fines recorded in February 1215 comes to more than £2700, to which can be added £950 in existing debts for which distraint was commanded, and a further unspecified although almost certainly handsome profit anticipated from the Irish exchange and mint. Escheats (heirless land), wardships and heiresses continued to attract hefty bids from those anxious to compete for such feudal 'incidents'. Hostages were expected to fine heavily for their release, whilst the apparent regularity of hostage taking itself testifies to the King's far from popular ways of disciplining his barons. So do the fines that arose from disputed inheritance or from the particular problems of the lordship of Meath, where the King had intervened decisively in 1210 to expel the previous lord, Walter de Lacy.13 So does the King's willingness to accept a higher fine, of 1000 marks, for the wardship of the heir of Thomas fitz Maurice, despite the fact that Thomas's wife had offered only half this sum, and apparently had her fine accepted, when the King was in Poitou in 1214. By contrast, when a son succeeded his father in an Irish estate, as was the case with William Sancmelle, or Hamo de Valognes, the King took reliefs of 200 marks (£133) and £100 respectively, in both cases more or less in line with the £100 that Magna Carta was to specify as the correct relief for a barony or earldom. Realpolitik thus rubbed shoulders with rapacity, no more obviously than in the repeated demands, throughout this list of Irish fines, that archbishop Henry should take the fines offered 'or more if you can get it' (vel maiorem si poteritis, repeated in ten of the twenty-seven transactions recorded here).

In other business this week, Thomas de Neville was asked to negotiate with various members of the Jewish community who had fled England since 1210, pleading poverty and their inability to pay harsh tallages and demands. Provided they supplied securities for future repayment, they were to be allowed to return.14 Part of another hefty tallage, imposed in 1214 on the men of Exeter, was to be forgiven in return for repairs to the city's walls: an indication that civil unrest was anticipated not just in the north or East Anglia, but in the far south west. These orders further imply that the King was planning to visit Exeter in person.15 The countess of Salisbury, whose husband, earl William, had been a prisoner of the French since the battle of Bouvines, was promised two oaks for firewood.16 This was hardly a lavish gift. It does nothing to support the rumour, later circulated by the French court historian Guillaume le Breton that, whilst earl William languished in prison, his half-brother, the King, incestuously seduced his wife.17

1 | RC, 205, and cf. RLC, i, 186b-7. For the ordering of witness lists as a guide to rank, N. Vincent, ‘Did Henry II Have a Policy Towards the Earls?’, War, Government and Aristocracy in the British Isles, c.1150-1500. Essays in Honour of Michael Prestwich, ed. C. Given-Wilson and others (Woodbridge, 2008), 1-25. |

2 | RLP, 127b. |

3 | The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, ed. H. Rothwell, Camden Society 3rd series lxxxix (1957), 144, and cf. N. Vincent, ‘Maulay , Peter (I) de (d. 1241)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn., Sept 2012) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18375, accessed 4 Feb 2015]. |

4 | RLP, 128. |

5 | For the King of Connaught, RLP, 127b. |

6 | RLC, i, 186b. |

7 | RLP, i, 185b. |

8 | N. Vincent, Peter des Roches: An alien in English politics, 1205-1238 (Cambridge, 1996). |

9 | RLC, i, 185b, 186. |

10 | RLC, i, 186-6b. |

11 | G. H. Orpen, Ireland under the Normans, 1169-1333, 4 vols. (Oxford, 1911-20), although for a detailed summary in English, see Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland Preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office in London, vol. 1 (1171-1251), ed. H.S. Sweetman (London, 1875), 83-4 no.529. |

12 | The Irish Pipe Roll of 14 John, 1211-1212, ed. O. Davies and D.B. Quinn, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 4, supplement (Belfast, 1941). |

13 | For the issues here, see C. Veach, Lordship in Four Realms: The Lacy Family, 1166-1241 (Manchester, 2014); idem, 'King John and Royal Control in Ireland: Why William de Briouze had to be Destroyed', English Historical Review, cxxix (2014), 1051-78. |

14 | RLC, i, 186b |

15 | RLC, i, 186b. |

16 | RLC, i, 186b. |

17 | Guillaume le Breton, 'Gesta Philippi Augusti', c.222, in Oeuvres de Rigord et de Guillaume le Breton historiens de Philippe-Auguste, ed. H.-F. Delaborde, 2 vols. (Paris, 1882-5), i, 311, blaming the later defection of William from John's cause upon the fact that 'ei certo innotuit relatore dictum Iohannem regem cum ipsius uxore, rupto federe naturali, commisisse incestum, dum ipse esset in Francia carceri mancipatus', and cf. See M. Strickland, ‘Longespée , William (I), third earl of Salisbury (b. in or before 1167, d. 1226)’,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn., May 2010) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16983, accessed 4 Feb 2015]. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)