Oblivious to events at Bouvines, John meets the papal legate

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

27 July 1214 - 2 August 1214

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

27-28 Jul 1214 |

RC, 200; RLC, i, 169 |

||

28-30 Jul 1214 |

RLP, 119b; RLC, i, 169 |

||

30-31 Jul 1214 |

RC, 200b; RLP, 119b; RLC, i, 169-169b |

||

31 Jul - 1 Aug 1214 |

RLC, i, 169b |

||

2-3 Aug 1214 |

RLP, 119b; RLC, i, 169b; Vincent, 'England and the Albigensian Crusade' |

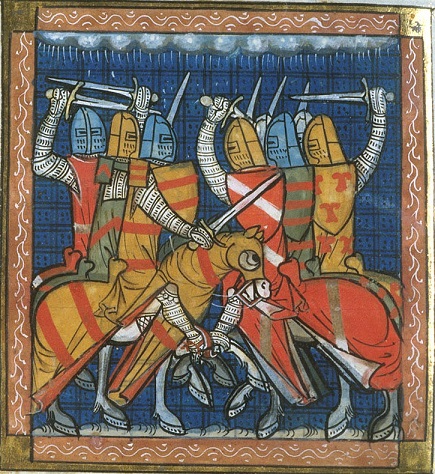

Sunday 27 July 1214 is one of the greater red letter days in the history of France. At Bouvines outside Lille, Philip Augustus not only defeated the most powerful coalition of enemies raised against him in the past thirty years, but cemented his control over all of the territories that, since the 1190s, he had conquered in nothern and central France. On the day of Bouvines itself, John was at Bouteville just south of the Charente, more than 600 kilometres from the scene of battle. Bouteville and the neighbouring Châteauneuf-sur-Charente were the sites of castles recently recovered by John from Hugh de Lusignan.1 We do not know exactly when news of the French victory filtered through to the English army. It travelled rapidly to Paris, but probably more slowly south of the Loire. Even then, it required time for rumour to be sifted from truth, and the full extent of the English defeat to be brought home to the King. As we shall see, it was perhaps not for over a week that the full magnitude of events in the north became apparent. Meanwhile, John's half-brother, William de Longuespée, and a large number of the English barons who had fought at Bouvines, were now prisoners awaiting ransom in Philip's custody. The entire army of the north, together with the diplomatic and financial efforts that had underpinned it, had collapsed in just a few hours of fighting.

In the south-west, and oblivious to events in Flanders, John seems to have focused first upon the defences of Angoulême, particularly those looking eastwards towards Limoges. At Angoulême on 28 July he sent representatives to a meeting of knights due to take place at Feuillade near Marthon (Foillatam de Mattath'), apparently as part of the ongoing tensions over the castle of Montbron, disputed since the death of Aimery le Brun a few weeks earlier.2 The vicomte of Limoges was reminded of the protection that the King had extended to Aimery's lands and castle, and on 30 July the knights of Ribérac, a little further south, were instructed to release their castle to Renaud de Pons, one of the King's principal lieutenants in the south.3 Provision was made for the support of William de Clisson (Clizun), perhaps defending Clisson in the northern Vendée, on what was now the frontier between French and Plantagenet zones of influence, 30 kilometres south of the Loire.4 On Wednesday 30 July, John himself set out from Angoulême, apparently travelling light and bringing with him only a small part of his household. Passing probably via Montignac to the north of Angoulême, and then eastwards via La Péruse, he seems deliberately to have avoided the main east-west road that would have taken him into the vicinity of Montbron. He entered Limoges on Saturday, 2 August.

On 1 August, from La Péruse on the extreme edge of the county of Angoulême, just before John's departure for the east, a letter was sent commanding the seneschal of Angoulême to see to the needs of the King's huntsmen and hounds, taking care that any mature stag (grassus ceruus) that they caught should be butchered according to the rules of the hunt. The haunches and rumps should go to the King (presumably as de facto count of Angoulême), the tongues and chines to Isabella, his queen, as countess.5 From this point onwards, the King's hunt, now separated from the King himself, remained a regular item of business, maintained in Angoulême and subsequently in Gascony.6 Rather like any military commander who brings his toys into battle, but then finds himself without the time to use them, the King himself had other more pressing concerns.

John's journey to Limoges was the second he had made since his arrival in Poitou that spring, Limoges itself being a city crucial to the eastern defences of the duchy of Aquitaine and traditionally the site of ducal coronations. John came there on 2 August specifically to meet the papal legate, Robert Courson, whose own letters report the King's arrival, 'leaving behind all his armies and wars'. Meeting the legate a league outside the city, John gave him honourable welcome. Presumably the legate was greeted in the same form in which John's father, Henry II, had greeted the Pope at the time of the Council of Tours in 1163. 'Discharging the functions of groom, on foot and holding the bridle of the Pope’s horse', Henry had 'led the Pope to the tent that had been made ready’: public gestures, modelled upon the office of groom (stratoris officium) that the ‘Donation of Constantine’ attributes to Constantine in his dealings with Pope Sylvester I, and that were clearly intended to distinguish the obedient and catholic King Henry (and later King John) from schismatics such as the emperor Frederick Barbarossa (who in June 1155 had notoriously refused to hold the pope’s stirrup on his first meeting with Adrian IV outside Rome).7 At Limoges, the King spoke personally with the legate of his determination to remain on terms with the Pope whilst defending his own rights.8 There is no suggestion at this stage, in either the legate's or the King's correspondence, that news of Bouvines had arrived in the south.

1 | RC, 141b. |

2 | RLP, 119b. |

3 | RLP, 119b. |

4 | RLP, 119b; RLC, i, 169b, orders of 29 July to William de Clizun to believe messages from the King, and of c.30 July to Peter de Maulay to allow William's representative 200 livres from the King's money. |

5 | RLC, i, 169b. |

6 | RLC, i, 170b-171, covering instructions of mid to late August. |

7 | Robert of Torigni, Chronica, in Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I, ed. R. Howlett, 4 vols, RS 82 (London, 1884–89), 215–16, with discussion of the context, both specific and general, by N. Vincent, ‘Beyond Becket: King Henry II and the Papacy (1154-1189)’, Pope Alexander III (1159-81): The Art of Survival, ed. P.D. Clarke and A.J. Duggan (Farnham 2012), 257-99, esp. pp.265-7. |

8 | Letters preserved in a unique copy in the Exchequer Liber B, London, TNA/PRO E 36/275 fo.198r-v, printed in N. Vincent, 'England and the Albigensian Crusade ', England and Europe in the Reign of Henry III (1216-1272), ed. B.K.U. Weiler and I.W. Rowlands (Aldershot 2002), 67-97, at 96-7. For the legate's activities in Limoges, where he took vows from numerous potential crusaders to Jerusalem, see Chroniques de Saint-Martial de Limoges, ed. H. Duplès-Agier (Paris 1874), 92, also in Bernard Itier, Chronique, ed. J.-L. Lemaitre (Paris 1998), 47. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)