John deals with Loretta de Braose and Isaac of Norwich

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

7 December 1214 - 13 December 1214

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

6-8 Dec 1214 |

RLP, 125; RLC, i, 180b, 181 |

||

9 Dec 1214 |

RLC, i, 181 |

||

10 Dec 1214 |

RLP, 125; RLC, i, 181b |

||

11 Dec 1214 |

RLC, i, 181b |

||

11 Dec 1214 |

RLP, 125 |

||

11 Dec 1214 |

RLC, i, 181b |

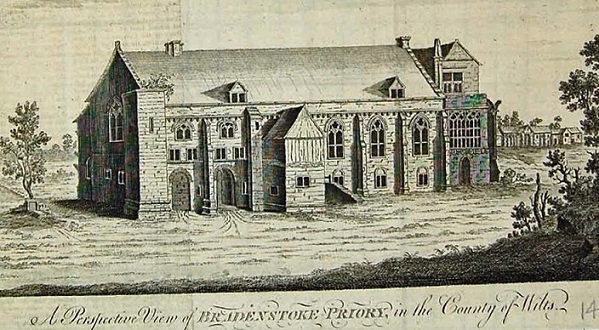

Leaving Gillingham on Monday or Tuesday 8-9 December, the King made his way northwards, via Devizes in the general direction of Gloucester. On 11 December, he was at the Augustinian priory of Bradenstoke in Wiltshire, a foundation with close connections to the Marshal family, to which the King offered letters of protection.1 From there, on the same day, he passed via 'Aston' (probably Aston Down) to reach the Cistercian abbey of Flaxley, this latter implying a crossing of the Severn several miles south of Gloucester, in order to approach Gloucester from the south west. From Bradenstoke, on 11 December, he wrote to commandeer 40 measures of the best wine to be taken from two ships impounded in the port of Bristol.2 His robes and furs were sent by cart from Corfe to Gloucester, under the protection of two London merchants, wrapped up against the winter weather.3

Various of the concerns of the previous week continued to occupy the King's mind, including the Bury election dispute. On 10 December, he instructed the archdeacon of Norwich to induct Ralph de Neville, future royal chancellor and bishop of Chichester, at this time a clerk rapidly rising in royal service, to the church of Morningthorpe. The letters were sent in duplicate, since the church was said to belong to the office of the sacrist at Bury, rather than to the abbey proper, so that both the convent and the sacrist were sent notifications of its disposal.4 This supplies further evidence of the hostility between the sacrist's party and the party of Bury monks supporting Hugh of Northwold. Potentially more significant, the King's willingness to invoke the authority of the archdeacon might be seen as an intrusion of episcopal authority within the Bury liberty, in theory exempt from such interference.

Before leaving Gillingham, on Monday 8 December, the court witnessed the most significant business of the week. Loretta, daughter of John's disgraced minister William de Braose, had been married in the late 1190s, when very young, to the earl of Leicester, Robert de Breteuil. On Robert's death, without children, in 1204, she had been promised an extensive settlement of dower within his estate and the enjoyment of her marriage portion, consisting of the Devon manor of Tawstock near Barnstaple. The earldom of Leicester meanwhile descended to Robert's two sisters. The eldest was married to Simon III de Montfort, by whom she gave birth to Simon IV de Montfort (d.1218). The younger sister was married to Saher de Quincy. Meanwhile, the death of Robert of Leicester, and the coincidental collapse of the succession to the Norman county of Meulan, brought two of the greatest lordships of Anglo-Norman England, originally created for the Beaumont family, back within the administration of the crown. After 1204,the Leicester estate was divided, with the earldom passing to Simon IV de Montfort. In compensation, Saher was offered a portion of the Leicester estate and promoted as earl of Winchester. Simon, who shortly afterwards emerged as leader of the Albigensian Crusade in southern France, continued to use the title 'Earl of Leicester' for the remainder of his life even though deprived of his English lands as an adherent of Philip Augustus. This left Saher de Quincy keen to acquire a larger share of his wife's lands. Loretta meanwhile was forced into exile following the disgrace of her father, William de Braose, and the arrest of her mother and eldest brother, supposedly starved to death by King John either at Corfe or at Windsor.5 On or shortly before Monday 8 December, in a charter witnessed by the justiciar, Peter des Roches, and a significant group of courtiers including her own brother, Giles de Braose bishop of Hereford, Loretta quitclaimed all seizures made from her estate by the King or anybody else appointed to its keeping. She further testified that she was unmarried and that she would not marry again save with the King's wish and consent.6 In return, on the same day, instructions were issued for the restoration of her dower in Devon, Dorset, Hampshire and Berkshire, followed by a promise that she would be compensated for any stock or carts taken away from her lands by Henry fitz Count.7

In all of this, a number of powerful baronial interests were engaged. Henry fitz Count, bastard son and heir of the late earl Reginald of Cornwall, was himself a highly significant figure in the west country. A cousin of King John (earl Reginald being an illegitimate son of King Henry I), he had been richly endowed with land, including the barony of Totnes confiscated from William de Braose. He was nonetheless denied succession to his father's lands and title as earl. To remove him from custody of Loretta's dower was to risk alienating the most powerful baron in Cornwall. Moreover, whatever was done for Loretta inevitably impacted upon the interests of Saher de Quincy, himself a regular attender at court but by this time, we can assume, already drifting towards the baronial camp. In 1215, Saher was to emerge as one of the leaders of rebellion. Of even greater significance, the King's peace with Loretta itself reflected a desire to settle scores with the Braose family, still enormously significant on the Welsh Marches, not just because of bishop Giles' position at Hereford but through intermarriage with the ruling Welsh princes.

In due course, Magna Carta clauses 7 and 8 were to specify that widows should have their marriage portions and dowers without hindrance, and in effect the right to remarry at their own pleasure, provided that such remarriage had the King's consent (assensum). The first of these provisions was openly flaunted by the quitclaim demanded from Loretta, abandoning all claim to seizures made from her dower. The second was tacitly denied by the insistence that Loretta's remarriage now be dependent upon the King's will, rather than her own (nec umquam me maritabo alicui nisi de voluntate et de assensu domini mei I(ohannis) illustris regis Anglie). At the same time, Loretta's quitclaim of all damages (nichil repetam, immo ea domino regi penitus remisi et quieta clamaui), should remind us of the undertakings that, at precisely this time, the King was seeking from churches and monasteries quitclaiming all compensation for 'seizures' (ablata) inflicted during the Interdict. These ecclesiastical quitclaims had been likewise governed by a promise to ask for no further compensation, employing the deliberately bland Latin verb repetere (in this context 'to ask again').8 Thus, both the Church and the secular baronage were obliged to connive in arrangements in which the King's security took precedence over justice or equity.

One final point: Loretta's quitclaim is the only item of business entered on the chancery Charter Roll for the entire period between the settlement with the Church on 21 November, and the King's Christmas court in late December 1214. Previously used to record charters in favour of the King's subjects, the Charter Roll itself was now employed to record charters issued by subjects very much in the King's interest. Loretta's charter was witnessed by her brother bishop Giles of Hereford and by William Malet. Both bishop Giles and the Somerset baron, William Malet, were to join the rebellion of 1215. Malet was himself the focus of attention during this week. On 8 December he was granted permission to divert a path through the wood of Ewhurst in Surrey.9 Two days later the King ordered the temporary restoration to William of the manors of Dullingham (Cambridgeshire) and Great Finborough (Suffolk), to be held by him until Twelfth Night, pending investigation of the circumstances that had brought these manors into the hands of Issac, Jew of Norwich, and thence into the custody of the King.10 Further land, seized by Isaac from Ralph fitz Bernard, son of Henry II's former courtier Thomas fitz Bernard (d.1185), was restored on 11 December, pending investigation of Thomas' debts to the King, both in chattels and in interest on money borrowed.11 These transactions were linked, since William Malet was a nephew of Thomas fitz Bernard, on whom his father had settled the manor of Dullingham as a marriage portion for Thomas' wife, Eugenia, herself the sister of William Malet's mother, Alice daughter of Ralph Picot.12

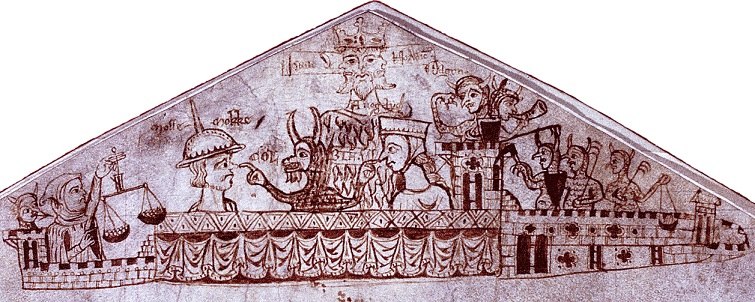

What was at stake here was the money-lending enterprise of Isaac of Norwich, perhaps the richest Jew in England, a patron of Hebrew scholarship, and a major figure in royal exploitation of the Jewish community from the 1190s onwards. In 1210, Isaac had been arrested and forced to redeem his life for the enormous sum of 10,000 marks. In 1213, he was transferred from imprisonment at Bristol to the Tower of London but almost certainly remained in captivity pending settlement of his debts.13 The King's interventions in December 1214 imply a desire to conciliate powerful barons who themselves owed money to the Jews, a pointer towards the interest to be taken in Jewish debt in clauses 10 and 11 of Magna Carta. Meanwhile, as the orders concerning William Malet suggest, any fine imposed by the King upon the Jewish community, as with the massive sum extracted from Issac of Norwich, was likely to have severe repercussions not only upon the Jews themselves but upon their Christian debtors, now forced to speed repayment in order to meet the King's demands In the particular case of William Malet, there was even more at stake. William, who had first risen to prominence in the 1190s as a companion of Richard I on Crusade, had in 1209 been appointed sheriff of Somerset, in direct response to the county's demand to have as sheriff a local man other than the courtier William Brewer. By 1214, William owed at least 2000 marks to the King but had in theory discharged this debt by a charter promising to serve the King in Poitou with ten knights and twenty other men at arms.14 What we find with the transactions over Issac's debts is therefore, once again, an entangled story of local and personal grievances complicated by the close inter-relationship between the English baronage, chiming with the wider aspirations of political society, directly linked to provisions that in due course were to be championed by the rebel barons of 1215.

1 | RLP, 125. |

2 | RLC, i, 181b. |

3 | RLC, i, 180b. |

4 | RLP, 125. |

5 | For all of this, see F.M. Powicke, 'Loretta, Countess of Leicester', Historical Essays in Honour of James Tait, ed. J. G. Edwards and others (Manchester, 1933), 247-274; D. Crouch, 'The Battle of the Countesses: The Division of the Honour of Leicester, March-December 1207', Rulership and Rebellion in the Anglo-Norman World, c.1066-c.1216, ed. P. Dalton and D. Luscombe (Farnham, 2015, forthcoming), and S. M. Johns, ‘Briouze, Loretta de, countess of Leicester (d. in or after 1266)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn., Oct 2006) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/47212, accessed 8 Dec 2014]. |

6 | RC, 202b, whose date can be inferred from the term set for the quitclaim, extending to the Monday after the feast of St Nicholas, i.e. 8 December 1214. |

7 | RLC, i, 181. |

8 | For both ablata and repetere, see the King's letters to the monks of Bury, RLP, 140 (data non repetendo), issued less than a week before Loretta's quitclaim. |

9 | RLC, i, 181. |

10 | RLC, i, 181b. |

11 | RLC, i, 181b. |

12 | For the complicated relations here, see VCH Cambridgeshire, vi, 158-60. |

13 | See R.C. Stacey, ‘Norwich, Isaac of (c.1170–1235/6)’, rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn., Jan 2008) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/37588, accessed 8 Dec 2014]. |

14 | See R.V. Turner, in ODNB ('William Malet (c.1175-1215)'). R. V. Turner, ‘Malet, William (c.1175–1215)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn., Oct 2005) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17881, accessed 10 Dec 2014]. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)