A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter: King John, Norman Cantor, and Mrs Simpson

April 2015,

I have been on the East Coast of the USA for the past week, speaking in Washington and Lancaster, and working in archives in Washington, Baltimore and Philadelphia. What follows, from Baltimore, represents the first of three posts from this American visit.

Sidney Painter (1902-1960) was one of the more distinguished American medievalist of his generation, and a leading authority on Magna Carta. Born in New York and educated at Yale, he taught at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore from 1931 until his death. His biography of King John, published in 1949, still ranks as a classic. It was originally advertised as the first of two volumes, this part supplying the political narrative, the other (in the event never published and in all likelihood never begun) covering the development of society and law. Intended with self-conscious teleology 'to delineate fully the background and immediate consequences of the issuance of Magna Carta', it remains an insightful study.1 In particular, it probes beneath the surface of the chancery and exchequer records, towards a closer appreciation of the links between record and reality. Whatever we may make of the overall architecture of the book (and there have been plenty who have criticized it, both at the time of publication and since), there is no doubting Painter's ability to spot the peculiar and revealing behind what to other readers might appear dull chancery routine.2

In the archives of Johns Hopkins there remain upwards of six boxes of Painter's papers.3 Readers will seek in vain here for any missing portions of the projected second volume of Painter's King John. If these ever existed (and there is little reason to suggest that they did), they are to be found neither in Baltimore nor amongst the papers of Fred Cazel (1921-2011), in effect Painter's literary executor.4 What remains, including Painter's lecture notes, has been very carefully sifted by Cazel and others, apparently in 1961, at the time that Painter's essays and addresses were collected into a memorial volume.5

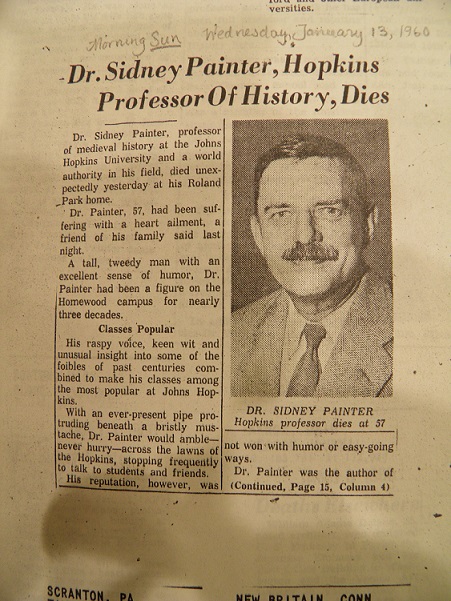

Painter died aged only 57 from a sudden heart attack. Some sense of the sad unexpectedness here emerges from the file of condolences received in 1960, and from the records of the memorial fund collected from friends and admirers: more than $3600 raised to pay for commemorations including the memorial volume of essays, a portrait by Mrs James Carey, and a small exhibition 'In Memoriam Sidney Painter' held at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore in September and October 1960.6 Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the Painter archive concerns not Painter himself (whose letters have been weeded almost to extinction) but the great trouble to which the authorities at Johns Hopkins then went to find a suitable successor. The Johns Hopkins archive contains detailed reports of nearly a dozen of the more distinguished young medievalists of the early 1960s, several of them happily still alive. These reveal a head of department, Frederic Lane, long before the days of the internet and cheap international telephone calls, seeking out the very best of advice and, in the end, making a choice that was both wise and painstaking. In the meantime, it is interesting to ponder the alternatives that were considered, not least the candidacies of C. Warren Hollister (1930-1997) and Norman Cantor (1929-2004). Neither of these figures, in future years, was to rival the scholarship and good manners displayed so effortlessly by Painter's chosen successor, John Baldwin (1929-2015).7 Since Norman Cantor went on to carve out a role for himself as the Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus of English medieval studies, I have printed the references supplied for him in 1960, by both David Knowles and Richard Southern, as an appendix below. They certainly help redefine the concept of damnation 'by faint praise'. They also shed light upon Cantor's conviction that he had in some way fallen victim to the prejudices (not least the anti-semitism) of the English establishment.

Meanwhile, at least some echoes of Painter's personality can be recovered from the John Hopkins correspondence files. It was Professor Kent Roberts Greenfield (1893-1967) who had brought Painter to Baltimore. In his memorial address, delivered on 21 May 1960, Greenfield recalled their first meeting at Yale, where Painter had received his PhD in 1930 under the supervision of Sydney K. Mitchell, the great historian of medieval English taxation.8 In Greenfield's telling:

'I was invited by an earnest young man in one of my classes to come to his room and meet a group of friends he liked to assemble from time to time to drink beer and hear one of his instructors talk. While I was undergoing this ordeal and talking, as I felt, through my hat, as one is likely to do on such an occasion, I saw a youth sitting in a window casement, with his long legs drawn up, smoking a pipe, and wearing even then, I believe, a moustache. He was looking at me curiously and skeptically, with a look that seemed to say: "You know that you are talking through your hat, or you ought to, if you don't". I got then and there the indelible impression of a very penetrating and formidable young man'

Another memorial address, by Painter's successor as head of department, Frederic Lane, refers obliquely to Painter's way with rules and regulations.9 Something of this, and also of Painter's own self-confidence as an alumnus of Taft and Yale, emerges from a letter that he wrote in December 1939 to Isaiah Bowden, President of Johns Hopkins.10 An anonymous complaint had been lodged against Painter for the use of language deemed inappropriate. In his defence, Painter sought to clarify what might have occurred:

'There seem to me to be two possibilities. Several years ago a Freshman lecture of mine offended the Catholics. My remarks were on the history of the sacraments, and while they were in accord with such historians as Lea, they were unjustified because they were unnecessary. I immediately changed the lecture in question and have known of no objections since. I have, however, some reason to believe that the more enthusiastic followers of the faith have neither forgotten nor forgiven. My last book received a very bitter review in a Catholic journal to which no review copy had been sent. The other possibility is that I have troubled some student of my undergraduate class in English history and that he merely was covering the scent. I rather doubt this because of the particular expression quoted. While I should hate to have to swear that I had never used it in class, it is certainly not a part of my ordinary classroom vocabulary. If a teacher is to maintain the respect of his students, he must keep a certain amount of dignity which makes the use of such terms impossible.

Nevertheless the letter raises a practical problem that rather troubles me. A course such as the one in English history must be for the most part a rather dull recital of complicated historical questions. This is especially true because the large proportion of pre-law students obliges me to emphasize constitutional history. If the lectures are to be effective pedagogically they must be lightened with a reasonable amount of anecdote. I was brought up the son of a New York obstetrician and have passed my life in circles that cannot be called unsophisticated. As a result I am simply unable to guess what may shock some more properly raised student. I do not mind giving them an occasional shock - it is a sound part of their education, but I hope some day to have enough experience to known when I am doing it. At the moment my solution of the problem is to try to observe two rules. I am careful to stay within the confines of acceptable academic language. Furthermore I say nothing in my purely male undergraduate class that I would not say in a mixed class. As the father of a very modern daughter you probably realize that this is no very burdensome limitation, but it seems to me to be a safeguard against violating the standards of ordinary good taste.

The whole question bothers me because of my recollection of two of my teachers at Yale - John Berdan and Chauncey Tinker.11 Berdan seemed to me to cross rather frequently the line between good taste and bad. Tinker never did, but he could skim it astoundingly close. My object is to follow Tinker in getting color without over doing it. The line is a very fine one and it requires pretty steady vigilance to stay on one side without being so conservative as to be colorless'

We shall return to Painter's 'colorful' language in due course. Meanwhile, in these present days of star chambers and student grievance procedures, it is instructive to read President Bowmen's reply12

Dear Sidney, In sending you the anonymous note I did not intend to elicit an explanation or a defense. You have my entire confidence. Nevertheless, I deeply appreciate the trouble you have taken to state your views. Neither the spirit of your letter nor the substance of it leaves anything to be desired. If you ever identify the piece of Silurian mud that is responsible for the letter will you give him an extra punch for me? Sincerely yours, I(saiah) B(owman)

Painter was a man of broad culture and sardonic wit. Asked to supply a self-description for one of those faculty enquiries that, even as early as the 1950s, had begun to bedevil academia, he took the occasion to respond with flippancy13

'I live very pleasantly in a house in the suburbs of Baltimore and spend the summers in a little place near Litchfield, Connecticut. I like to garden mildly and walk in the woods not too vigorously. I like to drink mildly with pleasant companions. I also like to sit in the sun and not do a damn thing. Actually my hobby is also part of my profession. My favorite entertainment is reading through the records of the Middle Ages and trying to reconstruct the life of the time. I also enjoy telling my students about it and writing on the same subject. While it would be helpful if the financial returns from my profession were a little larger, I have no regrets. I set out to be a professor of history in a first rate university and I am one. I hoped for modest professional recognition and I have it. I have spent the thirty years since graduation doing what I most like doing, surrounded by congenial colleagues and a thoroughly satisfactory family'

'Thoroughly satisfactory' here suggests a mastery of litotes.

An active member of his local community, as well as of his profession, Painter was in essence a liberal at a time when liberal intellectuals in the tradition of Henry Charles Lea or John Dewey struggled to cope with the perils of bigotry and mass delusion. A letter intended for the Baltimore Sun in 1949 suggests a desire on Painter's behalf to steer a middle course between tolerance and scepticism in approaches to the so-called 'Red Menace'.14 Almost the last letter that he wrote, dated 4 January 1960, only a week before his death, engaged with the distinguished historian of slavery, John Hope Franklin (1915-2009), seeking some sort of middle way over the issue of segregation and civil rights.15 Painter's instinct on both of these occasions was to defend liberty even at the cost of collective injustice (to Communists in the first instance, to Americans of color in the second).

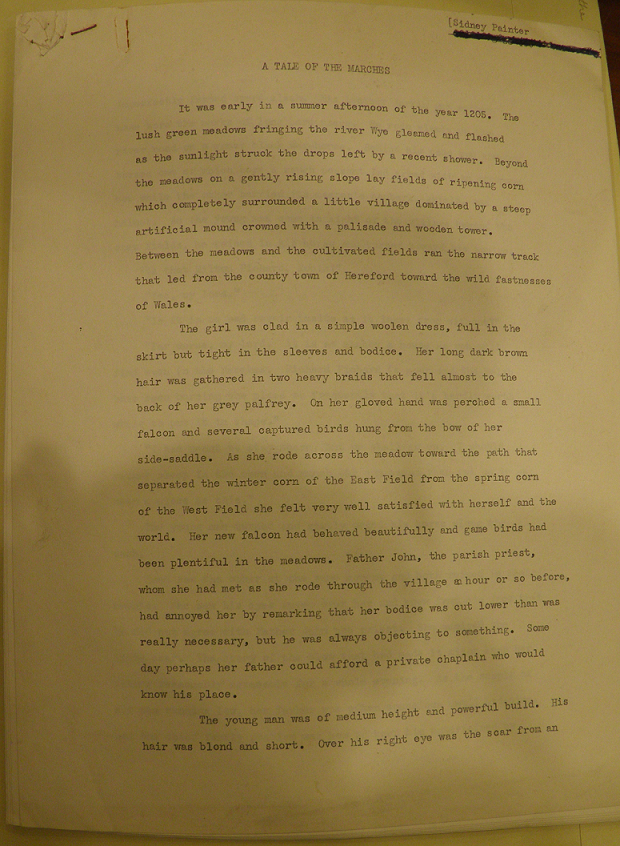

And so we come to perhaps the most interesting of Painter's literary remains. In the files at Johns Hopkins there survive several previously unpublished typescripts. In due course, I shall post on this site two of these, dealing specifically with Magna Carta. For the moment, however, and here amongst Painter's own papers, rather than his departmental archive, we find a previously unpublished short story, entitled 'A Tale of the Marches', undated, but carefully typed out and just as carefully preserved.16 Others of Painter's typescripts were used by Cazel for the Painter memorial volume of 1961. This 'Tale of the Marches' must have been considered for inclusion. Reading it, we can well understand why it was rejected.

'A Tale of the Marches' is of interest chiefly for what it reveals of Painter's inherent romanticism, in this instance through the fictional recreation of events of King John's reign that were otherwise treated with greater sobriety in Painter's books on William Marshal and King John. This is no lost masterpiece. Indeed, for a modern audience there are details here that may prove shocking: an undertow of violence, a jokey approach to rape, and an even more remarkable tolerance for the whipping of a young woman merely on the suspicion that she might have succumbed to the blandishments of King John. There is also the same, slightly blue, anti-Catholicism (castrated monks) of which Painter admitted being accused at Johns Hopkins. Most of these things were once a great deal more acceptable than they are today. Indeed, to those familiar with the films of Humphrey Bogart or John Wayne the level of sexual innuendo in Painter's story should come as little surprise. There is nothing here that cannot be found in Bogart's African Queen (1952) or Wayne's McLintock (1963). Even today, Bernard Cornwell makes a large fortune from writing in a similar style.17 We might even speculate, from various references within the story (beer-drinking father, daughter with advanced opinions, husbands struggling to assert control), whether this was a story of the 1940s intended for the entertainment of Painter's own wife and family.

Painter was by all accounts a kind and devoted father to four daughters, one of whom in 1946, aged only fourteen, compiled a list of his books, apparently as a typing exercise.18 Here, amongst the usual run of Pipe Rolls and chronicles, we find some surprising items. The Communist Manifesto is there (as no.945), no doubt for rebuttal rather than proselytization. So is Havelock Ellis' Life and Sex (no.986). So, as no.1079 on the list, between Mukerji's Son of Mother India and a book on Needlework, is Marie Stopes' Married Love. Married Love, indeed, is almost the last item in a catalogue that breaks off suddenly at no.1084 (George Boas, Philosophy and Poetry). We might speculate whether the list's fourteen year-old compiler had recorded rather more than her father anticipated. Meanwhile, we find a lot of poetry (not only Robert Burns but Robert Frost) and a great deal of literature, all the way from Sir Walter Scott in fifty volumes (no.714) to Sholokhov on the Don (nos 331-2) and Virginia Woolf's The Waves (no.381). Amongst the classics (or not so-classic), Scott rubs shoulders with collected editions of Charles Kingsley (no.607), Maurice Hewlett (no.627) and the twenty-one volume 'Anniversary' edition of Thomas Hardy (no.537). Painter's themes chime with those of all four of these authors, with Scott or Hewlett's derring-do, as with Kingsley or Hardy's frustrations. There is also plenty of Robert Louis Stevenson: Kidnapped (no.784), the collected Letters and miscellanea in 20 volumes (no.628), and what is described as item 14, of high priority both in listing and almost certainly in shelving: a copy of Treasure Island 'autographed by Ellen Terry'. Figuratively, and almost certainly physically, this rubbed shoulders with Painter's own books, on William Marshal (no.1), Peter of Dreux (no.3), English Feudal Barony (no.4) and French Chivalry (no.5). The only other volume so honoured (as no.2) was the book by Frederic Lane (Painter's Johns Hopkins colleague) Venetian Ships and Shipbuilders of the Renaissance. Clearly this was a household that respected books, some of them proudly displayed, others of them (like no.1079) on top shelves in theory hidden from childish curiosity.

Painter's 'Tale of the Marches' remains a puerile exercise, set in the years between 1205 and 1213, in the Herefordshire village of 'Milton Pichard'. Even the story's title is derivative, carrying echoes of such juvenile entertainments as Edward Duros' Otterburne: A Story of the English Marches (by the author of "Derwentwater") (London 1832), or, closer in setting, both in date and geography, Emily Sarah Holt's The Lord of the Marches, or The Story of Roger Mortimer (by the author of "Mistress Margery", "The White Rose of Langley" etc) (London 1885). Much of the bawdiness is cringe-worthy ('The appurtenances of the castle-mound do not attract me, but those of other mounds do'; 'Their prowess with weapons other than the sword', and so forth). To a modern audience, the reference to Richard the Lionheart as 'that gay monarch' is unintentionally drole, and I suspect that Painter himself would have cringed had some of the double-entendres been explained to him (not least 'Maud had her points'). No published author should be permitted to name a character 'Richard Pichard'.

Many details Painter borrowed from his own, more serious research. Thus, his description of castle defences reminds us of his pioneering 1935 article on English castles.19 The references to Isabella of Angoulême suggest reading in those sources that, in due course, were to produce Painter's articles on the King John's marriages.20 The bawdiness reflects his common sense approach to French chivalry, restored from the world of Victorian fair damsels to the much earthier realm of the knights (the 'chevaliers') who first gave the concept its name.21 Painter's French Chivalry (1940), dedicated to his wife, contained a chapter on 'courtly love' in which the refined Tennysonian view of such things had been contrasted with the reality of men on the make, dreaming of 'high-born virgin(s) burning with desire'.22 Various of the details on William de Braose (here 'Briouse') are borrowed from Sir Maurice Powicke's classic article of 1909, suggesting that William's downfall was the result of careless talk by his wife over the fate of Arthur of Brittany.23 Painter's story ends with a series of writs, of the sort with which he was familiar from Close and Patent Rolls. Even so, these particular examples are entirely invented. They would place the King at Marlborough on 2 June and at Clarendon on 10 June 1213. In reality, on these two days, John was at Wingham and Ospringe in Kent. Painter surely knew this. His hero, Roger de la Folie, likewise bears an entirely invented name, even though a Richard de Folariis occurs in April 1215, respited from debt.24 There are some peculiar spellings ('Mirabeau' for Mirebeau, 'Engelrand de Cigoiny' for Engelard de Cigogné, and so forth). All of this perhaps points to a date of composition before 1949, since in Painter's King John of that year, the name of Engelard de Cigogné (although not 'Mirabeau') is corrected spelled.25 Milton in Herefordshire was not known as Milton Pichard, and had no castle, even though the Pichards were indeed its lords.26 The references to Marlborough and the wife of Hugh de Neville take us back to a long debated entry in the Fine Roll for 1204, recording that Joan de Neville offered the King two hundred chickens 'to lie one night with her husband'. Painter himself discussed this incident at length, in his 1949 biography of the King27

Reviewing Painter's King John, in rather disdainful mode, Christopher Cheney approved Painter's 'liveliness' whilst deploring his slapdash way with detail. Painter's attempt to recreate the psychology of king, barons and pope was anathema to Cheney, as was his attempt to attribute the cause of administrative changes (be it in seals, warranty or sheriffs) to personal as opposed to official motives. 'Mr Painter', Cheney concluded, 'is not sufficiently rigorous in his analysis of evidence and is too imaginative in his interpretation of it'.28 How much more dismissive might Cheney have been had he been shown 'A Tale of the Marches'? As things stand, it was Cheney who in January 1960 contributed the brief and admiring obituary notice of Painter, published in the London Times.29 Even then, had Cheney cared to reflect on the matter, there were ways that even Painter's vivid reimaging of English history failed to do full justice to the romance of kingship.

In the 1930s, Sidney Painter became a Baltimore man through and through. His first decade in the city was passed at a time when the world's newspapers were obsessed with the antics of one particular Baltimorean. The daughter of Teackle Warfield, himself a younger son of the Baltimore flour-merchant, Hector Mactier Warfield, exploded upon the English social scene in a most unexpected way. Born in 1896, six years before Sidney Painter, Miss Bessie Warfield had been married and divorced six years before ever Painter published his first book, William Marshal. She was married and divorced again, in 1937, in the same year that Painter published his second book, Peter of Dreux. As a result of the latest of these adventures, Bessie Wallis Warfield is better known today as 'Mrs' Wallis Simpson. 'Low-cut' dresses never suited her. The outrage she inspired amongst English archbishops and courtiers was nonetheless little short of that expressed by Painter's 'Father John' for the antics of Milton Pichard's Lady Maud. Sex in high places (and palaces) became a theme, in the 1930s, not just of fictional romance but of all too real royal life. To that extent, as a period piece, as a reflection of Painter's own vivid reimagining of the thirteenth century, and as a reminder of the role that Baltimore has played in English royal affairs, 'A Tale of the Marches' deserves at least some of the attention devoted to it here. Certainly, it suggests that inside every good historian there lurks a bad historical novelist waiting to get out.

APPENDIX

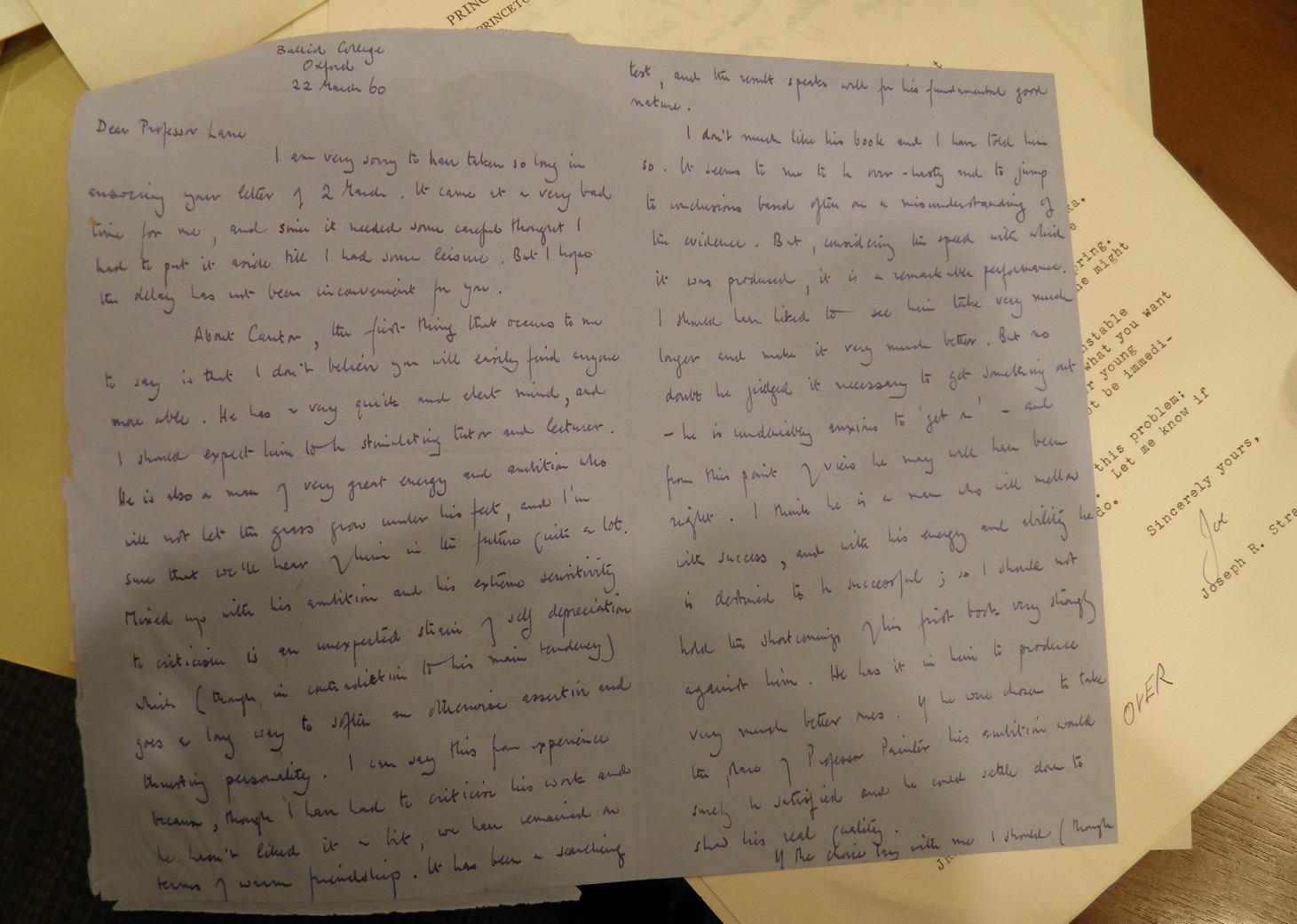

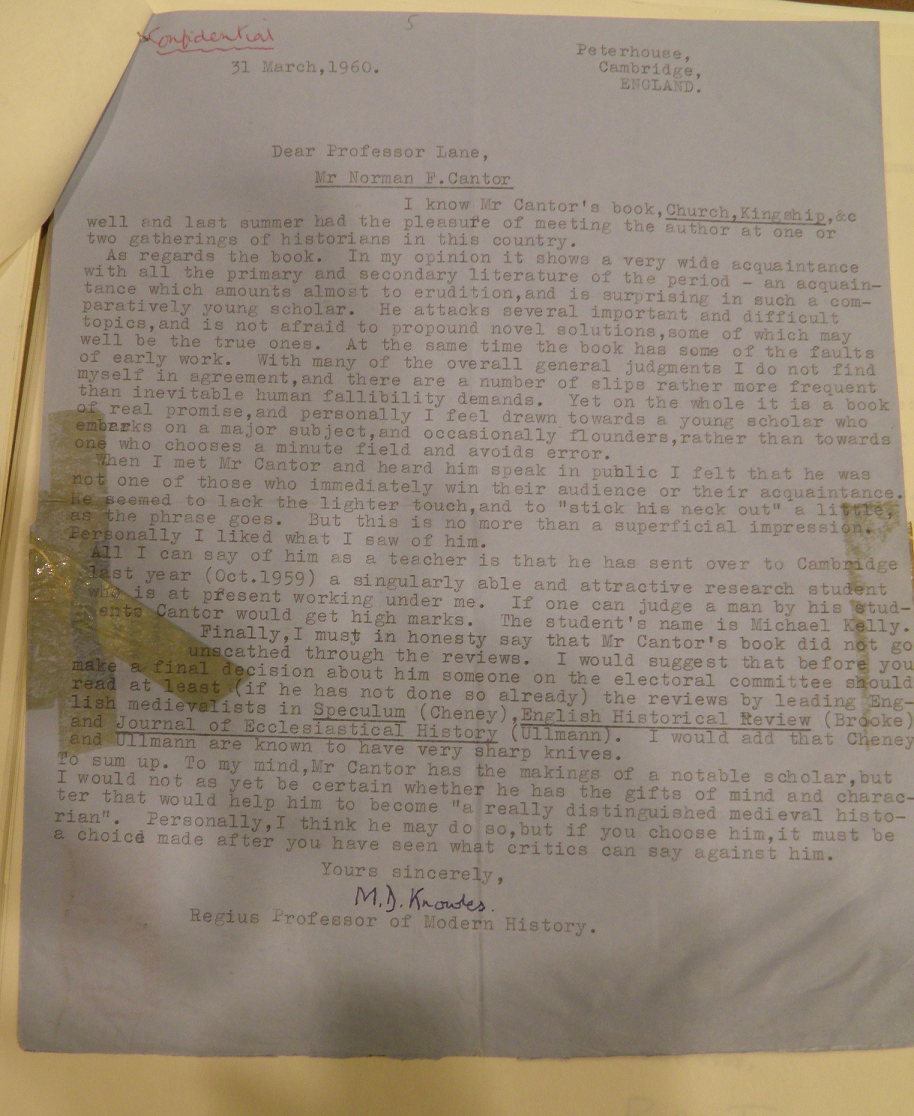

References supplied by Richard Southern and Dom David Knowles, on behalf of Norman Cantor, candidate to succeed Sidney Painter at Johns Hopkins University [March 1960]

JHU, Sheridan Libraries, Reference RG 04.110 (Department of History Papers, Subgroup 1 Series 3) Box 2 file 5 ('Correspondence')

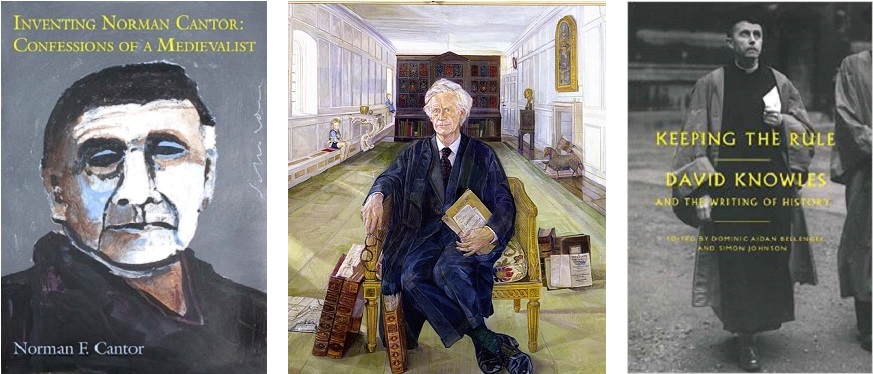

Now that all three principal parties are dead, it does not seem excessively indiscreet to bring these letters before a wider public. They certainly lend a new meaning to the phrase 'to damn with faint praise'. It is also worth speculating what their contribution might have been, had Cantor been made aware of them, to the tone of Cantor's own, now notorious memorializations of both Knowles and Southern, not only in Cantor, Inventing the Middle Ages (London, 1992), but in his autobiography, Inventing Norman Cantor: Confessions of a Medievalist (Tempe Arizona, 2002). For a perceptive (and highly critical) review of Cantor's Middle Ages, see Robert Bartlett, in the New York Review of Books (14 May 1992), with further correspondence over Cantor's portrayal of Ernst Kantorowicz, ibid. (13 August 1992). The reviews referred to by Knowles below of Cantor's book on Church, Kingship and Lay Investiture in England, 1089-1135 (Oxford 1958), are those by Christopher Brooke (English Historical Review, lxxv (1960), 116-20), Christopher Cheney (Speculum, xxxiv (1959), 653-6), and Walter Ullmann (Journal of Ecclesiastical History, x (1959), 234-7). Having been passed over at Johns Hopkins, Cantor in 1960 obtained a post at Columbia. He was accorded obituaries in both The New York Times (21 September 2004) and (more critically) The Telegraph (1 October 2004). Amongst his reminiscences of Oxford (Cantor, Inventing Norman Cantor,92-108) note in particular the delight with which he reports his return to England in 1959, arranged by Southern, during which Cantor's ten-month son vomited over his benefactor (p.106). See also (pp.106-8) his reminiscences of Knowles, who he first met in 1959, and who he credits with a reference for Princeton University Press that ensured Cantor's first book was published virtually without correction. Cantor reports that the book was praised by Sidney Painter, 'one of the three or four best American medievalists', leading to an offer from Johns Hopkins, after Painter's death, that he replace him: 'I taught his graduate students in the spring semester of 1960. They hated me, somehow feeling I had caused their beloved master's death'.

Balliol College

Oxford,

22 March '60

Dear Professor Lane,

I am very sorry to have taken so long in answering your letter of 2 March. It came at a very bad time for me, and since it needed some careful thought I had to put it aside till I had some leisure. But I hope the delay has not been inconvenient for you.

About Cantor, the first thing that occurs to me to say is that I don't believe you will easily find anyone more able. He has a very quick and alert mind, and I should expect him to be <a> stimulating tutor and lecturer. He is also a man of very great energy and ambition who will not let the grass grow under his feet, and I'm sure that we'll hear of him in the future quite a lot. Mixed up with his ambition and his extreme sensitivity to criticism is an unexpected strain of self deprecation which (though in contradiction to his main tendency) goes a long way to soften an otherwise assertive and thrusting personality. I can say this from experience because, though I have had to criticize his work and he hasn't liked it a bit, we have remained on terms of warm friendship. It has been a searching test, and the result speaks well for his fundamental good nature.

I don't much like his book and I have told him so. It seems to me to be over-hasty and to jump to conclusions based often on a misunderstanding of the evidence. But, considering the speed with which it was produced, it is a remarkable performance. I should have liked to see him take very much longer and make it very much better. But no doubt he judged it necessary to get something out - he is undeniably anxious to "get on" - and from this point of view he well have been right. I think he is a man who will mellow with success, and with his energy and ability he is destined to be successful; so I should not hold the shortcomings of his first book very strongly against him. He has it in him to produce very much better ones. If he were chosen to take the place of Professor Painter his ambition would surely be satisfied and he could settle down to show his real quality.

If the choice lay with me I should (though of course I don't know the rest of his field) think him a very suitable candidate. With all his faults, of which I am perhaps as conscious as anyone, I can think of none better. Although (perhaps because) he is by nature arrogant, I do not think that success so early in life will make him swelled headed (sic). He knows his faults too well for that, and I cannot imagine that he will stop working. My only fear is that seeing he goes down well writing this not entirely intellectually honest stuff of much of his first book, he will not bother to improve. Here one can only hope that his self-criticism will stand him in good stead. And of course even at his present level of scholarship he is quite impressive.

I have tried to tell you exactly what I think, and I hope I have succeeded. And I hope I have left the impression that Cantor is a man who will go far. He has already many of the qualities you are looking for, and he has others waiting to be developed if he wishes.

Thank you for the kind things you said about my book. And once more my apologies for my delay in writing.

Yours sincerely, R.W. Southern

Peterhouse,

Cambridge, ENGLAND

31 March 1960

Dear Professor Lane,

Mr Norman F. Cantor. I know Mr Cantor's book, Church, Kingship, etc well and last summer had the pleasure of meeting the author at one or two gatherings of historians in this country. As regards the book. In my opinion it shows a very wide acquaintance with all the primary and secondary literature of the period - an acquaintance which amounts almost to erudition, and is surprising in such a comparatively young scholar. He attacks several important and difficult topics, and is not afraid to propound novel solutions, some of which may well be the true ones. At the same time the book has some of the faults of early work. With many of the overall general judgments I do not find myself in agreement, and there are a number of slips rather more frequent than inevitable human fallibility demands. Yet on the whole it is a book of real promise, and personally I feel drawn towards a young scholar who embarks on a major subject, and occasionally flounders, rather than towards one who chooses a minute field and avoids error.

When I met Mr Cantor and heard him speak in public I felt that he was not one of those who immediately win their audience or their acquaintance. He seemed to lack the lighter touch, and to "stick his neck out" a little, as the phrase goes. But this is no more than a superficial impression. Personally I liked what I saw of him.

All I can say of him as a teacher is that he has sent over to Cambridge last year (October 1959) a singularly able and attractive research student who is at present working under me. If one can judge a man by his students Cantor would get high marks. The student's name is Michael Kelly.

Finally, I must in honesty say that Mr Cantor's book did not go unscathed through the reviews. I would suggest that before you make a final decision about him someone on the electoral committee should read at least (if he has not done so already) the reviews by leading English medievalists in Speculum (Cheney), English Historical Review (Brooke) and Journal of Ecclesiastical History (Ullmann). I would add that Cheney and Ullmann are known to have very sharp knives.

To sum up. To my mind, Mr Cantor has the makings of a notable scholar, but I would not as yet be certain whether he has the gifts of mind and character that would help him to become "a really distinguished medieval historian". Personally, I think he may do so, but if you choose him, it must be a choice made after you have seen what critics can say against him.

Yours sincerely, M.D. Knowles

Sidney Painter

'A Tale of the Marches'30

It was early in a summer afternoon of the year 1205. The lush green meadows fringing the river Wye gleamed and flashed as the sunlight struck the drops left by a recent shower. Beyond the meadows on a gently rising slope lay fields of ripening corn which completely surrounded a little village dominated by a steep artificial mound crowned with a palisade and wooden tower. Between the meadows and the cultivated fields ran the narrow track that led from the county town of Hereford towards the wild fastnesses of Wales.

The girl was clad in a simple woolen dress, full in the skirt but tight in the sleeves and bodice. Her long dark brown hair was gathered in two heavy braids that fell almost to the back of her grey palfrey. On her gloved hand was perched a small falcon, and several captured birds hung from the bow of her side-saddle. As she rode across the meadow toward the path that separated the winter corn of the East Field from the spring corn of the West Field, she felt very well satisfied with herself and the world. Her new falcon had behaved beautifully and game birds had been plentiful in the meadows. Father John, the parish priest, whom she had met as she rode through the village an hour or so before, had annoyed her by remarking that her bodice was cut lower than was really necessary, but he was always objecting to something. Some day perhaps her father could afford a private chaplain who would know his place.

The young man was of medium height and powerful build. His hair was blond and short. Over his right eye was the scar from an imperfectly fended sword slash. His leather jerkin and woolen hose bore the marks of long hard usage. He rode slowly up the river road on a great black war-horse. Behind him came two sumpter horses one of which bore a rough peasant lad armed with an enormous bow, while the other carried its master's hauberk, shield and helmet. As the young man came in sight of the village beyond the corn fields, he reined in his horse and turned towards his squire.

'Is that Milton Pichard, Robin?'

'Yes, my lord'

'Is it in as bad repair inside as it looks from without?'

'Far worse, my lord. It is as shabby a house as you will find even in the Marches. Richard Pichard is poor and the Welsh have been burning the place so frequently that it's hardly worth while to put it in shape'

'I had meant to stay there, but we shall go on. I should rather sleep in the open and munch our own bread than put up in as mean a place as this'

The young man turned and gently urged his horse along the path.

Each saw the other at the same moment and both reined in their mounts. She saw his eyes sweep over her and knew from his face that he did not agree with Father John the priest. She admired the livid scar. The story of the blow that had made it might keep her father reasonably agreeable for a whole evening. As the supply of ale was running low, her father was often conscious until bed-time, and the chief family problem was how to keep him entertained by some means other than by beating his wife and daughter.

'Where do you ride on this fair day, my lord?'

'To Huntington and Builth to find my lord William de Briouse.'

'That is a long journey from here. Why not stay the night at Milton Pichard? My father holds of your lord's son-in-law, Walter de Lacy, and will welcome you to his hall.'

'The appurtenances of the castle-mound do not attract me, but those of other mounds do. I shall be glad to accept the hospitality of Richard Pichard.'

They swung their horses into the path between the fields and rode towards the castle while the squire led the sumpter horse in their wake.

They rode along the village street past the mud and wattle huts of the villains, over the flimsy wooden bridge that spanned the moat, and through the gate in the outer-palisade that led to the bailli of the castle. There they left their horses in care of the grooms. On foot they crossed the narrow tilting ground and came to the inner-moat, a ditch some thirty feet wide and nine feet deep. The bridge was a single plank resting on two piers set in the moat. On the other side a steep, narrow path led up the mound to a heavy wooden gate in the inner palisade. They climbed this path and the girl called loudly to the porter to open the gate. A peephole was opened, a grizzled head stuck out, and this hole quickly closed again. They heard the porter's voice inside.

'My lord, my lord, the Lady Maud is at the gate with a very suspicious looking stranger. May I put a cross-bow bolt through him before I open the gate?'

'Is it a Welshman?'

'No, he looks English'

'Then you better let me have a look at him. I'll give you first shot if it seems safe'

In a few moments the peep-hole opened again to reveal the scar-covered face of Richard Pichard, lord of Milton Pichard.

'Who have you got there, wench?'

'I don't know his name, but he serves William de Briouse and is on his way to join him in Wales'

'The choicest rascals in England serve William de Briouse, and he and his sons are well fitted to rule them. But a vassal of the Lacies can hardly refuse one of them hospitality. Open the gate, porter'

The great gate swung slowly open and they entered a narrow passageway between the stockade and the wooden tower that rose within it. There Richard Pichard faced his guest. Richard was short and thick-set with black overhanging eyebrows. His face and neck were criss-crossed with scars that made him look almost as unpleasant as he undoubtedly was. His hand toyed fondly with the hilt of his dagger, while behind him the old porter nursed a fully loaded cross-bow.

'Now what's your name, sir?', he thundered. 'I am the only man in this household, and I cannot risk giving shelter to every rascal on the way to Wales with the sheriff behind him'

'I am Roger de la Folie, my lord, son of Reginald de la Folie who once held of Adam de Port and now holds of William de Briouse'

'Where did you get that scar?'

'That is almost royal, my lord. I got it from the sword of Hugh de Lusignan, count of La Marche, once the fiancée of our gracious queen, at the fight before Mirabeau'

'From all I hear, our gracious queen is as arrant a wench as Maud here, and my lord of Lusignan is a lucky man, but he is known as a good knight too and your slash is worth of a dozen of mine which came from the wild Welsh raiders'

Richard's hand left his dagger, he waved to the porter to lay aside his cross-bow, and he escorted his guest up the steep ladder that led to the door of his hall. The hall was a large rectangular room enclosed with rough boards nailed on great oaken beams. The only furniture was a trestle table, a few rough wooden benches, and three crudely carved arm chairs for the lord, his wife, and his daughter. Half a dozen gaunt dogs lay in the very dirty rushes that covered the floor and gnawed thoughtfully on the bones left from the last meal. On the wall hung Richard's armor, haubert (sic), helmet and shield, and a mixed array of various weapons. Richard picked up a large bone, banged it loudly on the table until a servant appeared, and called for ale. Then he turned to his guest and almost politely asked him to tell them of the fight at Mirabeau.

'King John was dallying at Le Mans with his fair young queen while the French attacked his castles along the Norman border. William de Briouse, William Marshal, and all the good knights of the court tried to rouse him. But the king rose at noon and was back in bed by eight of the evening. Then one day came a messenger hot from the south. Queen Eleanor, John's mother, was besieged in Mirabeau by her grandson Duke Arthur of Brittany and all the Lusignans. William Marshal remarked that as John had stolen Hugh de Lusignan's fiancé it was only fair to let him capture his mother, but the king swore by every part of God's body and called for his armor. Messengers were sent posting to order the seneschal of Anjou to gather his knights to join the king for the relief of Mirabeau. Never have I seen such a ride. The king seemed possessed. As our horses gave out, we seized fresh ones from the countryside. Beyond the Loire we met William des Roches and the Angevin knights, and just before dawn one bright day we reached Mirabeau. The besiegers were asleep in their tents when we struck. We could have killed them all easily, but the king wanted prisoners. It was in trying to capture the count of La Marche unhurt that I got this blow. The king bought my prisoner from me. My father was forgiven the hundred pounds he owed for shooting the king's deer and the fifty pounds he had promised if the king would forget the monk he castrated because he annoyed him about some tithes. I got twenty pounds in cash which I quickly used up in the taverns and bordellos of Rouen.'

As Roger talked a servant was dumping great pots of food on the table. He had barely finished his tale when the lady of the house entered the room. Dressed like her daughter except that she wore a badly faded mantle over her dress, she glanced apprehensively at her lord and was obviously relieved to see him in relatively good humor. Soon they drew the benches up to the table and went to work on the food. The first course consisted of the birds Maud had caught that day. The two ladies looked hopeful but not very optimistic as Richard and Roger plunged their hands into the pot in search of the choicest morsels. Richard was used to out-grabbing his women-folk, but he was not accustomed to real competition. Roger, who had spent some years among men-at-arms, was more than a match for his host. He could even afford to be generous and hand Maud a few good pieces - an act of politeness that so amazed Richard that he actually gave his wife a whole bird. When that dish was cleaned up, the servant brought in an enormous hunk of venison. Richard and Roger drew their knives and began to carve off great chunks and eat them down, occasionally remembering to toss one to the ladies.

After dinner the two men told tales of their battles and skirmishes. Roger had raided the French countryside in command of William de Briouse's Welshmen and had fine stories to tell of rapine, pillage, and slaughter. Richard had served in Ireland with Hugh de Lacy, his present lord's father. He told of masses of fierce Irishmen surrounded and cut down by the heavily armed knights. As the two men downed tankard after tankard of ale the slaughtered Irishmen grew more numerous and more ferocious and two or three churches filled with women and children were burned by the Welsh marauders. Soon they turned to their prowess with weapons other than the sword. Then it was dozens of fair-haired Irish maidens and dark-haired French peasant girls who had succumbed to the heroes. Few thirteenth century ladies were squeamish, but as the tales grew more and more explicit Maud and her mother looked at each other a little nervously and wondered if they should retire to the chamber. Fortunately the ale solved their problem. Richard slipped gently from his chair and went to sleep on the rush-strewn floor. The servant who had been quietly waiting for this usual conclusion to his lord's evening picked him up and carted him up the steep stairs towards the chamber followed by the dutiful lady Pichard.

Roger, who had managed to drink two tankards to his host's one, was by now in a most amiable mood. While no ladies' man himself, he knew how women were entertained in the best circles. He had served with his lord in King Richard's train in Aquitaine and had listened to many troubadors as they competed for that gay monarch's favors. Moreover his last assignment had been to escort Savaric de Mauleon, one of the most noted of living troubadors, from the field of battle at Mirabeau to a prison cell in the donjon of Corfe castle. As the ship belonged to Lord Savaric and was loaded with his Angevin wines, the trip had been a merry one and Roger knew all the latest love songs. While he could neither play an instrument nor carry a tune, the ale made him forget these slight disadvantages. Leaning back in his chair he sang Maud such of Savaric's songs as he could remember. He told her that her hair was like spun gold, that her lips were like a budding rose, that her throat was like the new fallen snow. As he progressed slowly down her person Maud was slightly embarrassed, but it was pleasant to feel like a lady of the great world of courtly love. Once she was well described physically she was told that she was the sum of all virtues - that the mere sight of her gave him the strength to slay a thousand knights. The valor of innumerable counts and great barons stemmed from her smiles. Would she grant some favor to her poor knight? Would she bestow a smile on him? Would she brush his cheek with her lips? Would she go to bed with him, all naked in his arms? Having by this time finished all the ale as well as his song Roger felt sleepy and suggested that they go to bed.

Maud led him up the ladder-like stairs to the room above the hall that served as the chamber. It differed from the hall only in its furnishings - three beds and a number of great chests. As they undressed in the light of the flickering torches, Roger was not too sleepy to admire Maud's charms. In fact he wondered for a moment ... but no, it was far too risky. Beside Richard there were the porter with his crossbow and the villagers. He had no desire to end his career in Milton Pichard. He climbed into bed and was soon fast asleep. Before dawn the next day he took leave of his hosts and rode on his way toward the distant Welsh hills.

The De Briouse clan was at the height of its power. The prime favorite of King John, William de Briouse, was lord of Bramber in Sussex, of Barnstaple and Totnes in Devon, of Kington in Hereford, of Gower, Brecon, Abergavenny, Builth, and the Three Castles in Wales. In Ireland the great lordship of Limerick was his for the conquering. His eldest son had married the daughter of the great Earl of Clare. Giles was bishop of Hereford, and Reginald was the husband of a daughter of Llewelyn, the mighty prince of North Wales. Walter de Lacy, head of that great house, and Hugh de Mortimer heir to the lord of Wigmore were his sons-in-law. In all South Wales and its Marches only William Marshal, the powerful earl of Pembroke, could match his power, and he was his close friend and ally. The De Briouse men rode high and free. The Welsh lords who were not under the protection of Llewelyn found their hamlets in flames and their people slaughtered. Non-resident lords who held estates in Herefordshire were likely to find them in the hands of Lord William's men.

Among these men rode Roger de la Folie. With them he burned the hamlets of the Welsh prince Wenowen. With them he plundered the manors of absent lords. With them he dreamed of fiefs to be won in Limerick or even in the Welsh Marches. Unfortunately, William had many men and fiefs were few. As time went on, Roger's mind turned to Maud and Milton Pichard. Lord Richard would not last too long. While the castle was no palace, it was better than nothing, and a younger son should not dally too long. Then Maud had her points - a fief could be gained by far less pleasant ways than by marrying her. Hence one day he approached Lord William in the great hall of Builth.

'My lord, I want a wife to keep me from sin and a fief to support me. Maud, daughter of Richard Pichard can do the one and her lands will help with the other. Will you give me leave to seek her hand?'

'I will do more than that. I'll lend you a dozen knights and give you the first cantred you can conquer from Welshmen or Irishmen. Woo your lady and then we shall see to an appropriate wedding gift'

So Roger de la Folie came once more to Milton Pichard. When Lord Richard had drunk enough ale to be amiable and not enough to be stupefied, Roger asked him for Maud in marriage. Richard was not enthusiastic.

'The third son of a man poorer than I am, who lives in a worse house than this; a reckless brawling rascal who has spent his youth following the wildest lord in England, has the nerve to ask for my daughter! As your wife she would be little more than a camp follower. And not much of a camp at that. She is the heiress to my lands, such as they are, and while they may never get her a decent husband they can buy her way into a respectable nunnery'

'But you forget, my lord, that I serve William de Briouse and speak with his leave and blessing. Wild he may be, but Lord William is close to being the most powerful man in England and is already the master of these parts. Well can he reward his servants - and make repentant those who scorn them'

'My Lord William rides high in the king's favor, but John's love is a weak support. He is a fickle and capricious prince. The great earl of Pembroke rots in Ireland - practically an exile. Why may not the same fate strike Lord William?'

'Because Lord William has a secret, a deep, disgraceful, bloody secret. He knows by what hand and at whose command young Arthur Plantagenet met his death'

'All the worse for him. Some day it will seem easier to destroy him than to appease him. Then will Lord William and his house fall from power'

'It can never happen. The king will not dare strike at the Briouses.'

'Perhaps, lad, but the other day I rode by Hereford town. In the streets were Poitevin cross-bowmen. Men say their chief is Girard d'Athies, the fiercest and savagest of King John's mercenary captains. What is more he is now sheriff of Herefordshire. I believe the king is about to strike. He dislikes men who are too powerful - especially when they know too much'

Long and late they argued but Roger could not move Richard Pichard. Eventually Richard withdrew in his usual efficient manner and Roger was left with Maud. She liked Roger and was filled with unbounded horror at the reference to a nunnery.

'Well, Maud, I guess there is nothing to be done. Not even Lord William would stand for the abduction of the daughter of a vassal of his son-in-law'

'Not even if it was done by license of the king's justices?'

Roger was not too quick-witted. He paused in perplexity. Then suddenly he saw what she meant.

'It will cost a mark at least, but Lord William would give me the money. Meet me at noon tomorrow in the fields near Hereford town'

She rode through the green meadows in the same low-cut dress. Ahead gleamed the spires of Hereford cathedral near the black bulk of the king's castle. Soon she saw him riding toward her on his great black charger. As they drew together, they leaped from their horses and met in the deep grass.

'Shall we make it real or just trust to appearances?', he asked.

She hesitated a moment.

'Whatever you think best'

He reached out and ripped her dress from collar to hem with one fierce stroke.

'That will do for appearances, but Girard d'Athies is known as a suspicious man. Let us make sure'

A few minutes later he sprang on his horse and headed up the river road for Wales. With a piercing shriek Maud raised the "hue and cry". Climbing on her palfrey with her dress hanging in tatters she rode into Hereford and up to the castle. There she called for the sheriff and the coroner and told them her tale. While riding peacefully along the Wye, she had met Roger de la Folie. He had taken her maidenhead by force and against her will, feloniously and in breach of the king's peace. Her torn garments were good evidence. Twelve good wives could discover still better proof. Girard de Athies summoned twelve good wives. With obvious suspicion he heard their report. But the law was the law. He ordered Maud to find pledges that she would be on hand to prosecute her case when next the justices came to Hereford and ordered his under-sheriff, Walter de Clifford, to either arrest Roger or find someone who would promise to have him in court. Walter de Clifford was himself a Marcher lord. He rode easily up the river road. Some miles beyond Milton Pichard he met William de Briouse's seneschal of Kington. Lord William would promise to have Roger in court when the time came.

The town square of Hereford was filled with people. The shire court was in session in the presence of the king's justices itinerant. The justices sat on a rough bench - an avaricious eyed baron, a portly abbot, and a neat, efficient looking professional judge. Near at hand stood the sheriff and around him clustered his Poitevin cross-bowmen. One could not tell whether they sought to protect their chief or to seek shelter near him from the obvious hatred of the local knights and men-at-arms. The chief judge solemnly intoned the sonorous Latin: 'Maud Pichard appeals Roger de la Folie that by violence and against her will, feloniously and in breach of the king's peace, he did rape her and take her maidenhead'. Roger stepped forward.

'My lord, we have come to an agreement and beg license to wed'

Once more the Latin forms rolled forth: 'They have come to agreement and offer the lord king one mark for license to wed.' Roger handed one of the sheriff's clerks a handful of silver coins and the clerk cut a wooden tally to serve as a receipt. Now no one could question their right to wed - it was by the king's will. The fact that Hereford cathedral was dead and deserted, that no marriage could be performed while the dread interdict hung over England, did not disturb them unduly. Nor did they feel any need to seek the blessing of Richard Pichard. Richard had beaten his daughter industriously and regularly for several weeks to persuade her to prosecute her case against Roger. When she left to go to court she heard him tell the porter to put a cross-bow bolt through her is she appeared again.

They told their story to Lord William in the great hall of Builth:

'Well done, Roger, well done. You got the best of Richard and the Poitevin sheriff. But it might be well to have a real wedding. The abbot of Margam is an old friend of mine. He knows my deepest secrets - even the secret. The Cistercians claim exemption from the interdict. Get married at Margam and then ride into Wales to Lord Reginald. Soon Poitevin bowmen and the feudal levies of England will be tramping these hills. Maybe you will not talk too much Maud, but Dame Matilda de Briouse does. She let the secret out and the king is moving against us. I am off to for Ireland. You will be safe with Reginald in the hills. Perhaps he can give you that cantred I promised as a wedding present'

The De Briouses were crushed. William fled to Ireland with his wife and eldest son, but John pursued them there. William escaped to France and died there in exile. Matilda and young William ended their lives in the gloomy cells of Corfe castle, where a well-instructed jailer forgot to feed them. But Reginald stayed free in Wales and with him Roger and Maud. While Maud served in the household of the Welsh princess, Reginald's wife, Roger followed his lord in raid after raid on the king's land. No village in Herefordshire or Shropshire was safe from them and their wild Welsh troops. Flaming houses and slaughtered peasants marked their path and their highland pastures grew fuller and fuller of fat stolen cattle. Such raiding was fun, and wonderfully safe. The old vassals of the De Briouses, the De Lacies, and their fellow Marcher lords dared not openly support the rebels, but they made no serious attempt to capture the marauders. When by some mistake on both sides the raiders met armed knights, the De Briouse battle-cry sent them into discreet retreat. While now and then the word of the presence of a company of Poitevin bow-men made the raiders change their route, there was no real danger from the king's men. John was busy with his quarrels with the pope and with Philip of France. Little he cared what happened on the Welch March.

As time went on it became hard to find villages to plunder. They did not rob Briouse, De Lacy, or Mortimer lands. The lands of other lords became blackened wastes. Only one untouched district remained - the fair land of Netherwent. But Reginald forbade his men to raid it. True, its lord was away in Ireland, and it was held by a weak garrison. It was the richest and most prosperous part of the Marches. One could not imagine more tempting prey. Many times Roger asked leave to lead his Welshmen down into its cattle-filled hillsides. Each time Reginald refused. They could raid the Marches at will because many of the local knights were their friends and the greatest lord of the land was indifferent. But if once the red flame spurted over a Netherwent village, the might of the house of Marshal would be turned loose. One could risk the ire of a Clifford or a Tresgoz with their half dozen or a dozen knights, but the Marshal's summons could bring two hundred and more knights to his banner.

Roger dared not directly disobey Lord Reginald. The fair land of Netherwent was safe. But on the middle Wye below Hereford town lay the castellary of Goodrich. As an outlying Marshal hold, it had been spared from attack. Its rich meadows were high with hay and its fields with corn. On the hillsides fed fat cattle and sheep. Roger had scouted the castle. Its ordinary garrison was a single aged knight and a half-dozen archers. One could plunder its villages thoroughly before the Marshal's friend and ally, John of Monmouth, could arrive with his knights. So on a bright May day in 1213, Roger swept down through Herefordshire at the head of his band. He had fifty Welsh spearmen and a dozen of his fellow exiles who had followed Lord Reginald into Wales. They slept on the hills and at dawn broke into the villages of the castellary (sic). While the Welshmen plundered the cottages and gathered the cattle, Roger and his horsemen rode up to the castle to see if there was a chance to take it by surprise. He could not hope to hold it, but it might be worth plundering.

Castle Goodrich was small, but it was no wooden tower on a mound. A grim stone keep looked down on a strong palisade, deep moat, and stone gate towers. The massive donjohn (sic) seemed to symbolize the might of the great earl who was its lord. Roger and his men drew rein before the gate and eagerly scanned the crenel(l)ations of the tower for a sign of the garrison. Suddenly, the drawbridge came clanking down and in a moment was covered by a mass of lance-points. A horn sounded and from fifty hearty throats came the fierce battle cry "God aid the Marshal." The astounded Roger then saw in the center of the cluster of spears the dread lion-shield of Earl William. He turned his horse and drove his spurs deep into its sides, but he was far too late. Around him like a cloud swept the fierce Irish spearmen, while straight at him came a levelled lance under the lion-shield. A minute later he lay stretched on the ground ten feet from his horse with a broken lance shaft sticking out of his right shoulder. In the distance he heard the cries of anguish as the Irish spearmen despatched his Welsh troops.

When Roger became conscious again he was lying on a bed in a corner of the hall of Castle Goodrich. The lance-head had been removed from his shoulder and the wound dressed, but when he moved he could feel irons on his ankles. Beside the bed stood a grey-haired knight.

'Well, you'll live to hand, young man'

'Who are you?'

'I am Geoffrey fitz Robert who follows Earl William. He left me to get you in good enough shape to move you to Gloucester. There the king's men will hang you as you so richly deserve'

'But what happened? Where did all those men come from?'

'Little news seems to reach into your Welsh hills. King John expected an invasion by Philip of France and called his host to meet them. Earl William led a hundred Irish spearmen to the muster on Barham Down. But John made peace with the pope's legate and the legate stopped Philip. The army was dismissed. Earl William and his men are on their way to Pembroke. Last night they lay here in Castle Goodrich. You picked a bad time for your raid. You will hang and unless I am much mistaken it will be soon'

Reginald de Briouse sat in the gloomy hall of a stone tower perched high on a Welsh hillside. Around him roistered his English followers and his Welsh spearmen. With him were Lady de Briouse and her woman, Maud de la Folie. One of the Welshmen approached Reginald.

'A messenger is here, a Welshman of Uske, bearing letters from the Earl Marshal'

'Bring him here'

A Welshman came up to Reginald and handed him a ragged piece of parchment that looked as if it had been torn off the end of a royal writ. Reginald called for his chaplain to read it to him. The priest took up the parchment and read:

'William Marshal, earl of Pembroke, to Reginald de Briouse, greetings. This morning I caught a party of your men plundering my demesne of Castle Goodrich. Their leader was knocked unconscious by my lance. His fellow horsemen were killed in the fight. My Irishmen slit the throats of his Welshmen. I am sending the leader to the king's men at Gloucester. As a loyal man I can do nothing else. But he is a sturdy young rascal and I bear him no grudge. Perhaps you can ransome (sic) him or at least delay his hanging. The peace with the pope will bring Giles back from France. The lord bishop may be able to save your reckless follower

Reginald frowned and his fingers drummed the arm of his chair.

'By God's teeth I'll not deal with King John in any way. Roger is a good knight and a loyal one, but he can hang before I make any offer to my mother's murderer. If Giles comes in time, he can do as he pleases. He is a true Briouse in some ways, but churchman and Briouse do not mix. Perhaps he can deal with the felon John'

Maud had listened in horror to the letter and her lord's decision. She drew the Welsh messenger aside and questioned him. Soon she approached Lord Reginald.

'My lord, the messenger tells me that Walter de Lacy is once more in the king's good graces and lies at his castle of Weobley. I shall go to him and ask him to plead for Roger'

'Walter always was as weak-willed and weak-minded as he is strong-armed. In the old days my father thought for him - now the Marshal does. Go to him by all means'

That night Maud set out over the hills with an escort of Welshmen who had promised to lead her through the Marches to Weobl(e)y.

Walter de Lacy was an enormous black-haired baron who had spent his life in a state of perpetual bewilderment. As the most powerful lord of Herefordshire he was perforce a central figure in the wild feudal politics of the Welsh Marches. As lord of Meath he was equally involved in the still more confused politics of Ireland. He had been used by Roger de Mortimer, by William de Briouse, by his own brother Hugh, earl of Ulster, and now by Earl William. Never had he been able to understand just what was going on. One day he would be the king's enemy, the next day his friend, and he never knew why he was in either category. Two years before, John had seized his lands and castles in the March and led an army to Ireland to take Meath away from him. Now he was the king's dear friend sitting quietly in his great Marcher stronghold. He had only a vague notion of how he had offended John - it had something to do with William de Briouse - and even less idea why he was in favor once more. He did not realize that there was a new master of the southern Marches, Earl William of Pembroke, and that a thick but amiable head with a hundred knights behind it could be very useful.

Walter received Maud joyfully. Richard Pichard was dead and his lands in Walter's custody. He remembered Richard vaguely as a companion-in-arms of his father at the conquest of Meath. The villagers of Milton Pichard said there had once been a daughter who had ridden away with a follower of the De Briouses. It took a good half hour to explain to Walter how the daughter of one of his vassals had been married without his assent, but once he understood he considered it an excellent joke. He readily promised to do what he could for Roger. He would consult his wife; she seemed to know what was going on. Margaret de Lacy was a daughter of William de Briouse, but a women could not follow her own courses. Nor had she ever been able to do much with her doughty lord. Now she mourned her father and mother while watching patiently for the return of Bishop Giles who might once more establish the house of Briouse and bring Reginald into the family fiefs. She heard Maud's tale.

'You cannot do anything, my lord,' she said. 'You will just get yourself in trouble again. There is a better way. Roger's older brothers were killed by the Poitevins when they seized Kington for the king. Roger if rightful lord of their fief. The king gave the barony to Roger de Clifford who is now Roger de la Folie's rightful lord. Roger de Clifford is the most outrageous plundering rascal in Herefordshire and a close friend of King John. He is the ideal man to help you'

So Maud went on from Weobl(e)y and sought out Roger de Clifford. He expressed great enthusiasm for her cause:

'Roger de la Folie is just the sort of an expert plunderer that I need. I should hate to lose him. But John is not likely to be easily moved in favor of a follower of Reginald de Briouse. I shall take you to the king, but you are more likely to succeed than I. No Clifford can forget that a fair lady can do more than any man with a member of the house of Anjou. We owe most of our lands to the charms of Rosamond'

The next morning Roger and Maud set out to find King John. It was no easy task. The restless monarch rarely stayed more than one night in any one place and rode long distances in a day. But Roger was an old hand at the game. He first went to Bristol and sought out a rich merchant, John de la Warr, who was the king's chief wine agent in the west of England. John led them to his office and looked through a pile of royal writs.

'Five tuns are ordered for Marlborough for the day after tomorrow. You can make that if you waste no time. Then the king must plan to go east for I have no more orders.'

As they rode into the town of Marlborough they saw that John de la Warr had been right. The streets swarmed with knights, men-at-arms, archers, servants, and prostitutes - the regular attendants of the royal court. Riding down the main street they suddenly heard the clash of arms and saw some men fighting fiercely at the doorway of a house. Maud gave a gasp of surprise, but Roger merely smiled.

'The men of two barons are arguing over which of their masters will lodge in that house. If anyone is killed and his master happens to be in very high favour, there may be trouble. Otherwise it's all part of the game of following the court'

Soon they reached the gate of the castle and faced two suspicious guards, but the arms of the house of Clifford were well known and they were admitted. Roger immediately sought out the constable of Marlborough, Hugh de Neville, High Forester of England, to ask who controlled the audiences with the king.

'Earl William of Salisbury is the only man who can get you and audience and he cannot do it easily. The king is morose and disagreeable even for him'They found the earl of Salisbury hard at work on one of John de la Warr's wine tuns. He greeted Roger boisterously:

'Welcome, Roger! I am always glad to see a Clifford. While the rabble's tale that I am half one myself is not true, I would feel honored if it were. My good father King Henry had a catholic taste in wenches, but they tell me that Rosamond was by far the best of the lot. Let us drink to Rosamond Clifford who might have been my mother'

When the earl heard their errand, he looked doubtful.

'The King is in a villainous bad humor. He wants to get off to Poitou and things go too slowly. He has been refusing to see anyone who wants anything. Not even Hugh de Neville can get near him. But for Rosamond's sake, I'll ask him if he will see you'

'Ask him if he will see either me or the lady here. It is her husband I come to plead for'

The earl looked Maud over carefully.

'Do you really want to see your dread sovereign lord? Have you considered it well?'

'Yes,' said Maud. 'For Roger de la Folie I will even see King John.'

The earl got up and went into an adjoining room. He was back in a few minutes.

'The king said, as I expected, that he would be eternally damned before he would see Roger de Clifford. The whole family was a nuisance. Every time he saw one it cost him a castle and five knights' fees. But he showed more interest when I mentioned the woman. He drained off what I should guess would be about his twentieth goblet of this strong Angevin wine and said that it was a king's sacred duty to receive all suppliants. I am to bring you to his chamber after supper'

Maud dressed carefully. She set the brooch that held her gown together rather lower than usual. As she did so she remembered Father John, but this time not even he could say it was unnecessary. When Earl William came for her, he smiled.

'Our king's tastes seem known even in Wales. But I forget, Prince Llewelyn has married a product of them'

He escorted her up the narrow, winding stair to the large chamber reserved for the king. John was a man of medium height with a handsome, sensitive face partly hidden by a short beard. He was sitting in a handsome carved chair, toying with a goblet of wine. He smiled at Salisbury.

'Ha, brother, you have brought me my fair suppliant. I shall send for you again when our interview is over'

The earl withdrew and the king's eyes turned toward Maud.

'You have heard that your king is over fond of women. That he debauches the wives, sisters, and daughters of his barons. That the mothers of his bastards come from the proudest houses of the realm. That moreover he does not scorn a gay peasant girl whom he glimpses on his wanderings. You hoped that a good look at your very effective charms might move me to enjoy you and in return free some rascal or other - your father, brother, or husband, I cannot remember which. What you have heard is true. The proudest ladies of England have lain in my bed while their fathers, brothers, and husbands fumed. I have taken them willing or unwilling as they have caught my fancy. It pleases me to humble and humiliate my barons. But no woman below baronial rank has ever been with me against her will. The house of Anjou is more eccentric than wicked. I'll free the worthless man you are interested in - it's worth it for no other reason than making Roger de Clifford happy without giving him a manor or two. Now if you will undress and give me pleasure, you can have this fair emerald ring and five tuns of this good Angevin wine'

'I do not care much for wine and the ring would look strange in Milton Pichard, my lord king'

'Ah! So I thought. What ho! Chamberlain! Call my lord of Salisbury'

In a minute or two the earl entered and looked curiously at the king and Maud.

'My good brother, have a writ issued to take care of this woman's husband. And tell Lady Neville that I am bored and would see her. Tell her she must ransome (sic) a folly'

In a lower room two clerks sat working at a table. One of them was obviously a man of position - well nourished, dignified, yet with the sharp look of the unscrupulous politician. The other was a poor clerk - a mere scrivener. Richard Marsh, archdeacon of Richmond and Northumberland and keeper of the king's seal, greeted the earl with the proper mixture of friendliness and unction. Richard was on the way up, but he had not yet arrived at the top and the earl was a powerful man, one of the few who could always reach the king's ear. The earl told him what was wanted and Richard dictated to the other clerk.

'John, by God's Grace, king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, count of Anjou, to his dearly beloved and faithful Engelrand de Cigoiny, sheriff of Gloucestershire and Herefordshire, greetings. I have pardoned Roger de la Folie in so far as it concerns me the offense for which he is imprisoned in Gloucester castle. When Roger de Clifford and Walter de Lacy promise that he will stand in court if anyone else wishes to plead against him, free him in their care. Witness William, earl of Salisbury at Marlborough on the second day of June in the fifteenth year of our reign'

Richard took the parchment, folded it, carefully dropped a blurb (sic) of wax on the fold, and stamped the great Seal on it. Then another letter was written addressed to all who might read it announcing the pardon and this was left open and the seal attached to it with a string. This was for Maud and Roger to keep as proof of the pardon. Richard handed the letters to Maud and held out his hand for his fee. Maud luckily had thought of that and produced it in silver pennies.

That night Maud slept on the floor near the bed of Queen Isabelle. The next day she and Roger de Clifford started for home. It took several days to find Walter de Lacy and get him to ride with them to Gloucester castle. Engelrand de Cigoiny had his clerk read and re-read the letters. He had him examine both seals with care. Finally he agreed they were probably genuine even if borne by two Marcher lords in favor of a border marauder. Roger was led to the smithy, his chains <were> struck off, and he was freed to his two lords. That night Walter de Lacy and Roger de Clifford argued until nearly dawn as to which of them had the chief rights over the combined fiefs of Roger and Maud. Each would get his part of the service, but which one would have custody of the heir? Finally Roger de la Folie suggested that he would proceed to prepare an heir against the day they got the argument settled.

As they rode towards Milton Pichard, Roger suddenly reined in his horse.

'Tell me, Maud, what moved King John to pardon me? Does he love Roger de Clifford so much?'

'It is hard to explain my lord and you wouldn't believe it anyway'

Roger thought for a moment and sprang from his horse.

'Maud I am going to beat you well and then forget about it.'

He walked over to a thicket and cut a switch. Maud looked at it and smiled.

'My lord that switch is too big - bigger than Holy Church allows'

'It is the size of my little finger'

'Oh, yes, but one must measure by my finger'

Roger smiled too. 'I'll cut two switches and tonight our chaplain will tell us which one is legal.'

They mounted and rode on. Late in the afternoon they rode into Milton Pichard. They found a man-at-arms holding the house as agent for Walter de Lacy, but they had Walter's letters ordering them to be given possession. The custodian had been dutiful and the place was well kept and well stocked - far more so than under Richard Pichard.

After dinner Roger sent for the parish priest and faced him with the problem of the switches. Father John was on in years and his knowledge of canon-law had never been great. But he had a keen recollection of the young Maud and her low-necked dresses. He gave Roger a brief sermon on the duty of husbands to keep their wives well disciplined and then suggested that the smaller switch would do as well as the larger if used vigorously enough. As soon as the chaplain left Roger told Maud to take off her dress. Then he beat her until the switch fell to pieces in his hands. The strokes hurt, but Maud was happy. She was the lady of a castle being beaten by her lord in their own hall. And it was pleasant to have wed an obedient son of the church. Her father had never let canon-law deter him from using a heavy leather sword belt on his lady.

Next day as they sat in the hall examining the accounts of the reeves, a servant announced the arrival of a royal messenger. A tall man in the garb of a royal forester came in followed by two servants carrying a large doe. He handed Roger a letter close bearing the royal seal. Father John who was at hand to help with the accounts read the letter.

'John, by God's grace, king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine and count of Anjou to his dearly beloved and faithful Roger de la Folie, greeting. I send you a doe from my forest to celebrate your homecoming. I would have sent a buck, but to you, Sir Roger, horns would not be appropriate. Witness I myself at Clarendon on the tenth day of June in the fifteenth year of my reign and sealed with my privy seal'

Roger thought for a long moment, looked at Maud, and smiled.

'You didn't deserve that whipping, but I'll forgive you the next one you do deserve.'

He raised the tankard that stood by his side:

'Long live king John, who is not as bad a fellow as I thought!'

1 | S. Painter, The Reign of King John (Baltimore, 1949), p.vii. |

2 | For the most detailed of the modern critiques, see W.L. Warren, 'Painter's "King John" - Forty Years On', Haskins Society Journal, i (1989), 1-9, notable not least for its comparisons between Painter on King John and Henry Kissinger on the Nixon administration. |

3 | Now divided between two principal parts, both Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University, Sheridan Libraries, the first deposited as ms.33 (Sidney Painter Papers) in 6 boxes, the rest as four manila files of correspondence and memorabilia, ibid. RG 04.110 (Department of History Papers, Subgroup 1 Series 3) Box 2 files 17-19, and Box 3 file 1 ('Talks'). For the sake of convenience in what follows these are referred to below as JHU Painter Papers Boxes 1-6, and as JHU Department of History Papers 2-3. I am most grateful to the Hopkins Librarian, Earle Havens, and to Amy Kimball and Jim Simpert of the library staff, for making my visit to Johns Hopkins so pleasurable. Gabrielle Spiegel and Lisa Enders helped me track down the portrait of Painter on the Hopkins campus. I owe a special debt of gratitude to Jenny Jochens. |

4 | See JHU Department of History 2.18 ('Memorials'), letter from Cazel to the Johns Hopkins departmental secretary, Miss Lavarello ('Dear Lilly', cf. Painter, King John, p.viii), 18 October 1960, reporting that 'I enclose a couple of Dr Painter's papers which do not concern me. But I am keeping the bulk of the file for the present. There are a number of things there which may prove very helpful'. So far as I can tell, a blue biro memorandum in ibid. 2.17 ('Curriculum Vitae') headed 'Private Papers of Professor Painter's now stored in the Sidney Lander Room' lists nothing that can no longer be found in the JHU files, although referring rather mysteriously to an otherwise unknown plan by Painter that had got only so far as rough file card notes, 'the projected book on Henry I'. For an outline list of the Cazel papers, now at the University of Connecticut, see <http://doddcenter.uconn.edu/asc/findaids/Cazel/MSS19880006.html#>. |

5 | S. Painter, Feudalism and Liberty: Articles and Addresses of Sidney Painter, ed. F. A. Cazel jr. (Baltimore, 1961). |

6 | JHU Department of History 2.18 ('Memorials'). |

7 | For Hollister, see the report supplied by Johns Hopkins' 'spy' on the West Coast, William Smith of the University of California: JHU Department of History 2.6 ('Medievalists B-H'), handwritten letter of 17 August 1960, reporting that he had found Hollister 'a better candidate on paper' than in fact, with 'little humor in him - but quite a bit of seriousness of outlook that seemed to me to border on a calculating nature ... I did not see as much grace, tact, humor, and over-all sureness of purpose in him'. Hollister's anxiety to obtain the post, evident from the sheer number of letters with which he bombarded Johns Hopkins, no doubt explains both the subject matter and the reverential tone adopted towards Painter, in Hollister, 'King John and the Historians', Journal of British Studies, i (1961), 1-19 |

8 | JHU Department of History 2.18 ('Memorials'), Report of the memorial ceremony at Gilman Hall, 21 May 1960. |

9 | Ibid., 'Sidney always cared more about individuals than about rules. Rules there have to be of course, and Sidney did his full share of work in the university in making and unmaking them, but always with the firm quiet assumption that rules have to be handled so as to permit individuals to grow'. |

10 | JHU Department of History 2.19 ('Papers and Correspondence'), Painter to Bowden, 21 December 1939. |

11 | John Berdan (1873-1949), a Shakespeare scholar. Chauncey Brewster Tinker (1876-1963), a leading authority on James Boswell and one of the first to 'discover' the Boswell's paper, subsequently scooped by Ralph Isham. |

12 | Ibid., Bowman to Painter, 26 December 1939. Bowman (1878-1950), geographer, PhD Yale (1905), President of Johns Hopkins from 1935. |

13 | JHU Department of History Papers 2.17 ('Curriculum Vitae'). |