A King John Christmas Special: Partridges and a Pear Tree

December 2015,

As his diary for December 1215 reveals, King John spent his last Christmas at Nottingham, preparing for what was to be a great campaign of revenge and reprisal waged as far north as Edinburgh. Whether there was an opportunity for carolling at Christmas 1215 remains unknown, although we do know that the 'Laudes', the great acclamation of Christian kingship opening 'Christus Vincit, Christus regnat, Christus imperat', had been sung before the King at least three times in the preceding year, at Christmas 1214 and again at Easter and Pentecost 1215.1 Certainly, the volume of business recorded on the chancery rolls for December 1215, including half a dozen writs issued on Christmas Day itself, suggests that the court was exceptionally alert at a time more usually given over to feasting and wassail.2 King John's self-indulgence in food and drink is difficult to gauge, since we are rarely informed whether the wine and other luxuries commanded for the court were for the King or more generally for his courtiers. We nonetheless have a famous account of John's Easter Mass in 1200, during which messages were sent up to the presiding bishop, not once but three times, imploring him to cut short his sermon so that the King might dine after his Easter fasting.3 Something of the culture of the court can be detected in the life-style of the French-born abbot of Beaulieu, one of the King's favoured diplomatic envoys, who in October 1215 was accused before the Cistercian General Chapter of keeping a guard dog tethered to his bed on a silver chain, of dining off silver plate presented to him by servants on bended knee, and of engaging in a public drinking contest, in a game known as ‘garsacil’ played out between the abbot, three earls and forty knights.4

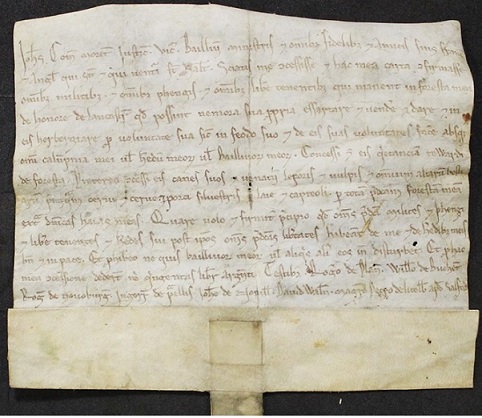

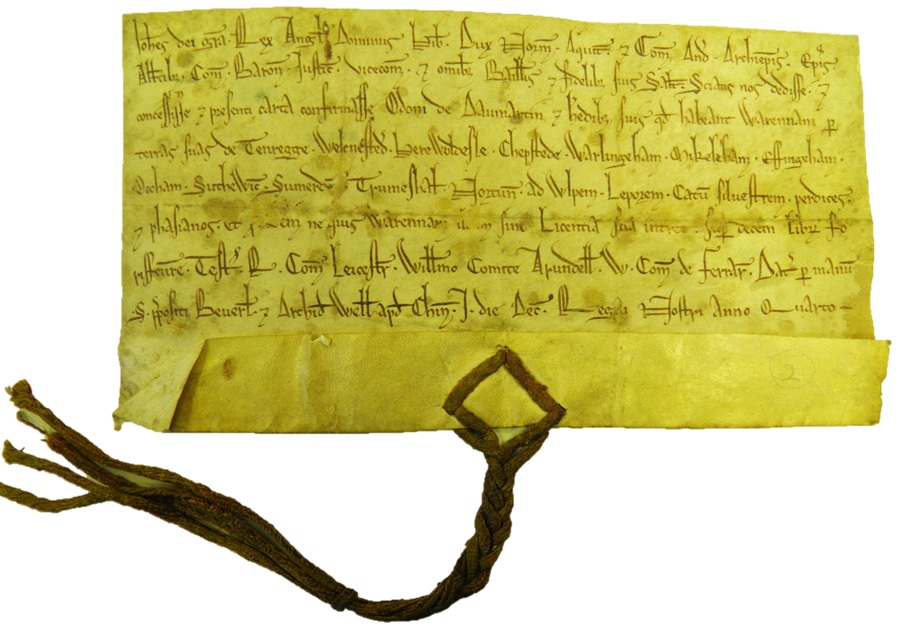

As for the twelve days following Christmas, culminating in the great feast of Epiphany (6 January, marking the arrival of the three kings at Christ's nativity), our project is now in a position to supply King John with at least two of the attributes most closely associated with this season of the year. The first of these, a partridge (or rather partridges in the plural), can be found in an original charter that came to light at the very beginning of our project, back in December 2012, in the Minet Library (a hidden gem of a collection, in the south London borough of Camberwell). By this, the King conferred rights of free warren upon Odo de Dammartin, a leading tenant of the Clare lords of Tonbridge, with lands scattered across Surrey, Sussex and Kent. Odo was distantly descended from the family of the counts of Dammartin (north of Paris) from which sprang Renaud de Dammartin, count of Bolougne iure uxoris and one of the more significant prisoners taken by Philip Augustus at the battle of Bouvines in July 1214.5 Besides founding the hospital, subsequently Augustinian priory, of Tandridge in Surrey, Odo de Dammartin makes occasional appearances in the records of John's reign, in August 1215, for example, when he was instructed to release an Irish hostage previously entrusted to him by the King.6 He subsequently joined the rebellion, presumably as a result of his extensive landholding from Richard de Clare, earl of Hertford, in Surrey and north Kent.7 As King John's charter of 1 December 1202 reveals, Odo also held family lands at Southwick in Sussex, and scattered across East Anglia, at Norton in Suffolk and Strumpshaw in Norfolk.8 In all of these estates, in December 1202, he was promised rights of free warren, so that no-one might enter his lands without his permission, on pain of a £10 forfeit.

Licences for warren can be found at least as early as the reign of Henry I. Eight such awards are preserved from the reign of King Stephen (1135-1154), and more than fifty from the reign of Henry II (1154-1189): part of a growing tendency towards the privatization of land use and the restriction to the seigneurial élite of rights over hunting within forest both royal and private.9 From the mid-1150s, Henry II's licences generally specify that warrens are to be exempt from the right of 'chase' (or hot pursuit) otherwise claimed by huntsman, and from the taking of hares.10 In other instances, we have the emergence, again from the 1150s, of licences conferring the right to keep hounds within the King's forest and to pursue game, specifically mentioning the hare and the fox, and occasionally (in charters of Henry II otherwise suspected to be forgeries) the wild cat.11 Richard I, by the 1190s, had undoubtedly and authentically extended such privileges to include the hare, the fox and (in one or two instances) wild goats and/or cats.12 Notably absent here is any general licence to pursue those beasts (boar and above all deer) that were considered to be the King's especial prerogative.13 In the 1190s, for example, before his accession to the throne, we find the future King John granting the men of the Lancaster forest the right to keep hounds and to hunt for hares, foxes and 'all other beasts' save for deer, wild boars and sows ('porci siluestris et laie') and goats.14 At much the same time, certainly before 1199, John confirmed the men of Devon in their right, apparently established as early as the reign of Henry I, to hunt for goat, fox, wild cat, wolf, hare and otter.15 In Ireland, by contrast, where seigneurial privileges were more generously distributed, as early as 1185, John had granted his chamberlain, Alard fitz William, the right in his own lands to pursue deer, pig, hare, fox, rabbits ('cunini') 'and all other game'.16

King John's licence for the warrens of Odo de Dammartin conforms to the general pattern of such awards, save in one significant respect. It includes amongst the beasts reserved to Odo not just the hare, the fox and the wild-cat, but partridges and pheasants. This in itself supplies our very earliest reference in any English administrative source to both species of birds, here presumably included amongst the beasts of the chase to be pursued with falcons rather than (as was the case with hares, foxes and cats) with hounds. The pheasant, perhaps first introduced to England in Roman times, thereafter assumed to have been reintroduced before the Norman Conquest, makes little or no impression either upon the medieval bestiary or upon treatises that describe falconry.17 The partridge, a species native to England, is described both by Pliny and by Isidore, albeit with no especially exotic characteristics.18 As opposed to herons and cranes (the favoured prey of kings), neither pheasants nor partridges were especially prized in falconry.19 Hence, perhaps, their inclusion amongst the licensed (and hence, by implication, inferior) beasts of the chase. Even so the more general pattern revealed here, with royal licences first mentioning beasts in general, then hares, then hares, foxes and cats, and now hares, foxes, cats, pheasants and partridges, is of a pattern with the wider tendency towards the elaboration of seigneurial privilege, and hence of the reservation to lords of an ever greater variety of rights and in this instance, species of animal. As such, this teaches us something of importance to our wider understanding of the relations between kingship and lordship in the years prior to Magna Carta.

It also, of course, supplies us with a seasonal reference to partridges, themselves famously recorded in the 'Twelve Days of Christmas': a counting song, first reported in 1780, almost certainly adapted from earlier French models. As the great authorities on such songs, Iona and Peter Opie point out there may be some support for the idea of partridges as perching birds, as a result of the introduction to England, c.1770, of the red-legged (or French) partridge, distinct from the native common (or grey) partridge, that nests at ground level.20 In any case, the idea of 'A partridge in a pear tree' leads us to the one such pear-tree indubitably associated with King John. According to the unnamed monk of Bury St Edmunds whose chronicle reports the election of Hugh of Northwold as abbot, in March 1214, Richard, the deceitful precentor of Bury, approached Peter des Roches, the King's justiciar, at Northampton 'beneath a certain pear tree', presumably in the grounds of Northampton Castle.21 The reference here may be precise and topographical. Alternatively, it may be intended to link the plot hatched between Richard of Bury and Peter des Roches to the generally scandalous qualities of pear trees, from St Augustine to Shakespeare associated with temptation, seduction, and ultimately with the male genitalia.22 In either case, it allows us to associate King John and his court not just with partridges, but with the partridge's favoured roost. And not just with any old pear tree, but with one growing in the royal precincts of Northampton: the town where, in May 1215, the barons first raised their standards in rebellion against the King.

One could extend this search. In July 1215, for example, Peter des Roches, as justiciar, was commanded by the King to purchase a quantity of 'anulos pulcros' to be sent as gifts to the King of Norway.23 The number and substance of these rings is not specified. Need we doubt, however, that there were five of them, all of the very best gold? We have elsewhere drawn attention to the King's commands of March 1215 for hens (albeit 'fat' or 'good', rather than 'French') to be fed to his best falcons.24 Again, need we doubt that there were at least three such hens? To go any further would be far-fetched. Nonetheless, as a Christmas offering, I trust that the King's partridges and pear tree will suffice.

At the end of Magna Carta's 800th anniversary year (an anniversary that will not be forgotten by anyone who has participated in it), the time for celebration is rapidly coming to an end. It is time now to look to the future. Henry Summerson's commentaries on the 1215 Magna Carta are nearly complete. The search for original charters of King John is unlikely to produce any vast number of new additions, although a large body of edited material remains to be uploaded to our website. David Carpenter will continue to update his work on the copies of Magna Carta in all of its various issues. King John's diary has reached Christmas 1215 and will carry on, God willing, to the King's death in October 1216. With a further 43 weeks of materials still to be written and uploaded, this has become not so much the comfort as the bane of its author's old age. We have posted nearly forty features since this project began. Rather than sign off, I very much hope that contributors will continue to post new material as topics arise. In the meantime, I wish everybody - colleagues, contributors, and readers - a Very Happy Christmas and the best of all possible New Years.

APPENDIX

Notification of the King's grant to Odo de Dammartin of rights of free warren in Odo's lands of Tandridge, Godstone (alias Walkingstead/'Welenested'), Harrowsley (in Horley), Chipstead, Warlingham, Mickleham, Effingham, Peckham (in Camberwell, Surrey), Southwick (Sussex), Somerden (in Chiddingstone, Kent), Strumpshaw (Norfolk), and Norton (Suffolk), including rights over the fox, the hare, the wild cat, partridges and pheasants. Chinon, 1 December 1202

A = Camberwell, Minet Library/Lambeth Archives, Surrey Deed 3606. Endorsed:Tannerygge d(e) warrenna concess(a) per dominum regem (s.xiii/xiv). Approx. 210 X 89 + 27mm. Sealed sur double queue, pink and yellow cords through 3 holes, seal impression missing.

Pd (from A) R.N. Bloxam, 'A Surrey Charter of King John', Surrey Archaeological Collections, liv (1935), 58-9.

Ioh(ann)es Dei gratia rex Angl(ie) dominus Hib(ernie) dux Norm(annie) Aquit(anie) et com(es) And(egauie) archiepiscopis, episcopis, abb(at)ibus, com(itibus), baron(ibus), iustic(iis), vicecom(itibus) et omnibus baill(iu)is et fidelibus suis salutem. Sciatis nos dedisse et concessisse et presenti carta confirmasse Odoni de Daumartin et heredibus suis quod habeant warennam per terras suas de Tenregge, Welenested', Herewoldesle, Chepstede, Warlingeham, Mikeleham, Effingeham, Pecham, Suthewic', Sumerden', Trumeshal', Nortun' ad wlpem, leporem, catum siluestrem, perdices et phasianos, et pro<hib>em(us) ne quis warennam illam sine licentia sua intret super decem libr(arum) forisfacture. Test(ibus) R(oberto) com(ite) Leicestr', Will(el)mo comite Arundell', W(illelmo) com(ite) de Ferrar'. Dat' per manum S(imonis) prepositi Beuerl' et archid(iaconi) Well' apud Chin', i. die Dec(embris) regni nostri anno quarto.

John, by God's grace King of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine and count of Anjou, sends greetings to archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, barons, justices, sheriffs and all his bailiffs and faithful men. Know that I have granted, conceded and by this present charter confirmed to Odo de Dammartin and his heirs that they are to have rights of warren throughout their lands of Tandridge, Godstone (alias Walkingstead/'Welenested'), Harrowsley (in Horley), Chipstead, Warlingham, Mickleham, Effingham, Peckham (in Camberwell, Surrey), Southwick (Sussex), Somerden (in Chiddingstone, Kent), Strumpshaw (Norfolk), and Norton (Suffolk), for the fox, the hare, the wild cat, partridges and pheasants. And we forbid on pain of a forfeit of £10 that anybody enter that warren without their license. Witnessed by Robert earl of Leicester, William earl of Arundel, William earl Ferrers. Given by the hand of Simon provost of Beverley and archdeacon of Wells, at Chinon, on the first day of December in the fourth year of our reign.

1 | King John’s Diary and Itinerary 21-27 December 1214, 19-25 April, 7-13 June 1215. |

2 | King John’s Diary and Itinerary 20-26 December 1215. |

3 | Adam of Eynsham, Magna Vita Sancti Hugonis, ed. D.L. Douie and D.H. Farmer, 2 vols (Oxford, 1985), ii, 142-3. |

4 | Statuta Capitulorum Generalium Ordinis Cisterciensis, vol.1, ed. J.-M. Canivez, Bibliothèque de la Revue d'Histoire Ecclésiastique ix (Louvainm, 1933), 445 (1215), no.48: 'Abbas Belli Loci in Anglia qui coram tribus comitibus et quadraginta militibus inordinate se habuit in mensa, scilicet bibendo ad garsacil, et qui habet canem cum catena argentea ad custodiendum lectum suum, et qui adduxit secum seruientes seculares in equis qui ei, flexis genibus, ministrant, et qui in vasis argenteis de consuetudine facit sibi ministrari, et de quo multa alia dicuntur etc'. |

5 | The standard authority is now J.-N. Matthieu, 'Recherches sur les premiers comtes de Dammartin', Mémoires publiés par la fédération des sociétés historiques et archéologiques de Paris et de l'Ile-de-France, xlvii (1996), 7-59, but with only limited attention to the family's English property. |

6 | RLP, 151b. |

7 | RLC, i, 328b, and for his wider career, see R.N. Bloxam, 'A Surrey Charter of King John', Surrey Archaeological Collections, liv (1935), 58-65; C.A.F. Meekings, 'Two Dammartin Deeds', Sussex Archaeological Collections, cxvi (1978), 399-400, reprinted in Meekings, Studies in Thirteenth-Century Justice and Administration (London, 1981), ch.16. |

8 | For the lands in general, see Bloxam, 'A Surrey Charter of King John', 60-5, where the author misreads the place-name given in the original as 'Pecham' (i.e. Peckham) as 'Occham' (i.e. Ockham). |

9 | In general, see David Crook, 'The "Petition of the Barons" and Charters of Free Warren, 1227-1258', Thirteenth Century England VIII, ed. M. Prestwich and others (Woodbridge, 2001), 33-48; idem, 'The Development of Private Hunting Rights in Nottinghamshire, c.1100-1258', Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, cv (2001), 232-43. For licences for warren issued by Stephen, see Regesta, iii, nos. 27, 88a, 173, 227, 236, 349, 558, 661. For those under Henry II, see The Letters and Charters of King Henry II (1154-1189), ed. N. Vincent and others (Oxford, forthcoming 2016), nos.18, 332, 356, 400, 405, 433-4, 438, 577, 590, 594, 596, 639, 654, 746, 821, 896, 917, 1098, 1196, 1212, 1303, 1349, 1400, 1507, 1510-12, 1524, 1527, 1530-1, 1714, 1758, 1951, 1965, 2018, 2094, 2128, 2222, 2260, 2289-90, 2315, 2375, 2562, 2581, 2620, 2671, 2798, and for references to such licences now lost, see nos.965, 1000, 1023, 1091, 2021, 2024, 2741. Amongst these, a majority claim to confirm or restore privileges already enjoyed in the time of Henry I: nos.18, 356, 400, 590, 746, 821, 896, 1098, 1196, 1303, 1349, 1400, 1507, 1510-11, 1524, 1527, 1530, 1714, 1758, 1951, 1965, 2018, 2222, 2260, 2289, 2562, 2581, 2620, 2700, 2798. Reference to a charter of William I or William II as well as to Henry I is made in no.596. |

10 | Generally in one or other variation on the phrase 'ne quis in ea <terra> fuget vel leporem capiat'. King Stephen's licences fail to specify any particular game, save in one instance (Regesta, iii, no.558) for 'bestia'. For specific reference to hares, see Letters and Charters of Henry II, ed. Vincent, nos.18, 332, 356, 400, 405, 590, 594, 639, 654, 821, 896, 917, 1098, 1196, 1212, 1303, 1349, 1400, 1507, 1510-11, 1524, 1527, 1531, 1758, 1951, 1965, 2018, 222, 2260, 2289, 2562, 2581, 2620, 2700, 2798. For other combinations, see reference to 'aliquam feram' (nos.433-4, 2290), to doves (no.2315), 'fox, hare and cat' (no.577, almost certainly spurious), fox and hare (no.2375, almost certainly spurious), hare 'vel aliam bestiam (no.917, for Fécamp, and the only one of these licences specifically granted to a Norman institution and applied to lands in Normandy rather than to Norman lands in England). |

11 | Letters and Charters of Henry II, ed. Vincent, nos.44 (hare and fox), 296 (hare and fox as in the time of Henry I), 579 (hare and fox), 580 (hare and fox, spurious), 1801 (hare, fox and cat ('munlegum'), spurious), 1849 (hare, fox and cat ('murilegum'), almost certainly spurious), 2080 (hare and fox), 2167 (goat, hare and fox, probably spurious), 2565 (hare and fox), 2605 (hare and fox). |

12 | Pending the appearance of a more thorough edition of Richard's charters, see the references supplied by The Itinerary of King Richard I, ed. L.Landon, Pipe Roll Society n.s.xiii (1935), nos.100, 178, 187, 194, 228, 241, 263, 319, 544, including grants of hunting rights over wild cats to Alan Basset (August 1198, from an original now TNA E 40/5924), the monks of Colchester, Peterborough and Waltham. |

13 | See here Letters and Charters of Henry II, ed. Vincent, nos.435-6, forbidding the pursuit of the archbishop of Canterbury's game, referring specifically to deer, goats and hare. |

14 | Preston, Lancashire Record Office DD St (Weld of Stonyhurst) Box 17 ('concessi eis canes suos et venatum leporis et vulpis et omnium aliarum bestiarum preterquam cerui et cerue et porci siluestris et laie et capreoli per totam predictam forestam meam extra dominicas haias meas'), printed (from later copies, without notice of the original), The Lancashire Pipe Rolls, ed. W. Farrer (Liverpool, 1902), 418-19, subsequently confirmed in a charter of John as king, 9 October 1199 (RC, 25b-6, from an original, itself now Preston, Lancashire Record Office DD Ho/RR964). |

15 | Exeter Cathedral Library ms. 2514 ('quod habeant canes suos et alias libertates sicut melius et liberius illas habuerunt tempore eiusdem Henr(ici) regis, et reisellos suos, et quod capiant capreolum, vulpem, cattum, lupum, leporem, lutr(em) ubicumque illa invenerint extra reguardum foreste mee'). |

16 | Dublin, National Library of Ireland, Ormonde Deeds ('concessi etiam ei in predictis terris venatum cerui et bisse et dame et porci et leporis et wlpis et cunini et cuiuslibet alterius venationis'), whence (calendar only) Calendar of Ormonde Deeds, ed. E. Curtis, vol. 1 (Dublin, 1932), 3-4 no.7. |

17 | For their introduction to Rome, apparently from the land of Colchis, on the south-eastern corner of the Black Sea, see G. Jennison, Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome (Manchester, 1937), 109-10. |

18 | For the partridge, see the sources assembled at The Medieval Bestiary. |

19 | For herons and cranes as the object of King John's interest, see N. Vincent, 'Feature of the Month: March 2015 - King John’s Lost Language of Cranes: Micromanagement, Meat-Eating and Mockery at Court '. |

20 | The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, ed. P. and I. Opie (Oxford, 1951), 122-3, drawn to my attention as part of the exceptionally informative Wikipedia entry <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Twelve_Days_of_Christmas_(song)>. |

21 | The Chronicle of the Election of Hugh Abbot of Bury St Edmunds and Later Bishop of Ely, ed. Rodney Thomson (Oxford, 1974), 50 ('proprius aduocauit dominum Wyntoniensem sub piro quadam'). The feminine noun 'pirus' denotes the tree rather than the fruit (neuter noun, 'pirum') of the pear, whence 'pirarium' (an orchard of pear trees). |

22 | Marjorie O'Rourke Boyle, Divine Domesticity: Augustine of Thagaste to Teresa of Avila (Leiden, 1997), 3-13, esp.pp.11-13, citing, amongst others, Chrétien de Troyes' Cligès, the Comoedia Lydiae (c.1175) and Chaucer's 'Merchant's Tale', as noted by P. Piehler, The Visionary Landscape: A Study in Medieval Allegory (London. 1971), 101; K.P. Wentersdorff, 'Imagery, Structure, and Theme in Chaucer's Merchant's Tale', Chaucer and the Craft of Fiction: Essays in Medieval Poetics, ed. L.A. Arrathoon (Rochester, 1986), 50-2, 6, n.55. |

23 | RLC, i, 168. |

24 |

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265