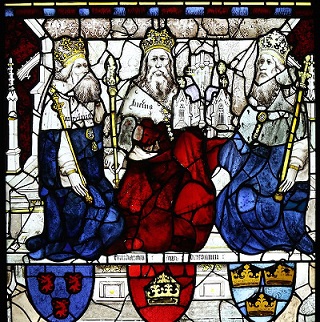

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris and Pope Eleutherius’ letter to Lucius, King of the Britons in the early thirteenth century

September 2015,

Katherine Har is a DPhil candidate in the History Faculty at Oxford University, researching legal writing in late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century England and the Leges Anglorum Londoniis Collectae. From 2014 to 2015, she was an intern in the Department of Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts at the British Library working on the Library's major temporary exhibition: Magna Carta, Law, Liberty, Legacy.

It has long been recognized that the London collection of laws, known as the Leges Anglorum Londoniis Collectae, contains a version of the so-called Leges Edwardi Confessoris that throws light upon contemporary interpretations of the relation between king and people in the years leading up to King John's issue of Magna Carta in 1215.1 In what follows, an attempt is made to point out the particular significance to this debate of a text interpolated into the London Collection's version of the Leges Edwardi: a letter supposedly issued in the name of Pope Eleutherius to Lucius ‘King of the Britons’.

Following a discussion of the development of murder fines and before an account of the extent of the king’s mercy, the standard text of the Leges Edwardi Confessoris states that, ‘The King, moreover, who is the vicar of the highest King, was established for this, that he rule and defend the kingdom and people of the Lord and, above all, the Holy Church from wrongdoers, and destroy and eradicate evildoers’.2 The text then looks back to the Merovingian and Carolingian past to provide precedents for this claim, citing correspondence from Pippin and his son Charles to Pope John,3 and the papal rescript in reply. The early thirteenth-century Leges Anglorum Londoniis Collectae compiler, when including the Leges Edwardi in his compilation of the laws of the kingdom, saw this passage as an opportunity to further expand on the idea of the responsibilities of a good, Christian king by employing an even older parallel which also provided a precedent closer to home – the British king Lucius and Pope Eleutherius.

Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica recounts how Lucius wrote to Pope Eleutherius requesting guidance on becoming a Christian and how ‘his pious request was quickly granted and the Britons preserved the faith which they had received, inviolate and entire, in peace and quiet, until the time of the Emperor Diocletian’.4 The story of Lucius’ role in the early British church and his letter to the Pope in Rome had first appeared in the Liber Pontificalis,5 one of the sources drawn on by Bede.6 It later circulated widely and appeared in Nennius’ Historia Brittonum7 as well as a range of later works including Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britannie8 and William of Malmesbury’s De antiquitate Glastoniensis ecclesie9. Geoffrey of Monmouth, in particular, elaborated on the story of Lucius’ role in the conversion of Britain with an account of Lucius welcoming two missionaries sent from Rome, Faganus and Duvianus, who converted the king and his people, the pagan priests, high priests, spiritual advisors, and temple-servants and then established the diocesan organisation of the kingdom.10

However, while there are many references to Lucius writing to Eleutherius seeking his advice, what is lacking in all of these is an account of the contents of or the text of a papal rescript to Lucius’ missive. It is this letter which is found in the Leges Edwardi Confessoris, as included in the Leges Anglorum compilation; there is no earlier version. Both the papal rescript received by Pippin and Charles and this additional text of Pope Eleutherius’ letter to Lucius are very clear that the actions of a king make him worthy of his royal title. This was a recurring motif widely borrowed during the medieval period from Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae. It reappeared, for example, in different forms, both in John of Salisbury’s Policraticus and in Gerald of Wales’ De Principis Instructione which discuss the distinction between king and tyrant.11 The Leges Edwardi’s account of Pippin and Charles concludes with a quote from the Books of Psalms, and correspondingly Eleutherius’ letter is replete with quotations from the Psalms, with its royal connotations, providing Old Testament commentary on Christian kingship. Alongside these are additionally quotes from the Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, and the Gospels of Luke and Matthew.

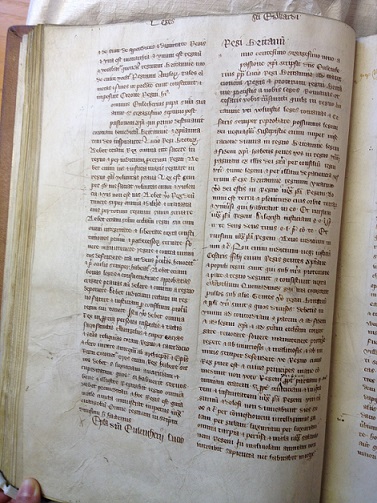

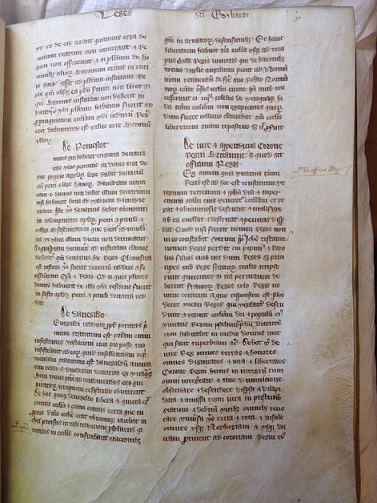

In constructing a chronological account of the laws of England extending back to the Anglo-Saxon period, the Leges Anglorum compiler drew on a compilation known as the Tripartita, made up of the Articles of William I, Version 3 of the Leges Edwardi Confessoris,12 and a genealogy of the dukes of Normandy and kings of England. In terms of length, the Leges Edwardi Confessoris make up the bulk of the Tripartita compilation and the standard 39-chaptered Version 3 of the Leges Edwardi text appears in the Leges Anglorum compilation in an extensively interpolated and reorganised form. As noted by Felix Liebermann, many of the lengthiest of the emendations and interpolations are to be found in this compilation. Here, what was Chapter 17 of the Leges Edwardi in Version 3 of the text appears earlier than expected. Promoted to follow a description of the Danegeld and a statement that the church was exempt from those payments; the new interpolations fill almost two full folios.

The compilation known as Leges Anglorum Londoniis Collectae is an early thirteenth-century legal compilation produced in London during the reign of King John. The volume was later separated into two parts, half currently residing at the John Rylands Library in Manchester (MS Latin 155 [Rs]) and half at the British Library (MS Additional 14252 [Ai]).13 The compilation begins for the most part with anonymous twelfth-century privately produced legal treatises organised chronologically: the Quadripartitus, the Tripartita, the Leges Henrici Primi, and Glanvill. This is followed by an assortment of texts providing an account of the laws and franchises of the city of London. This offers a more municipal focus with special emphasis on the unique liberties enjoyed by the city. Woven into this broad account of the legal past and present are additional texts of a more narrative nature, giving the overall impression of a narrative of legal heritage with a strong sense of continuity. The otherwise familiar legal texts are also interpolated with accounts which highlight both the antiquity and pre-eminence of the city of London and its citizens.

David Carpenter has suggested that the Leges Edwardi, and particularly its account of how Pippin and his son Charles received guidance from Pope John on good kingship, would have been familiar to Gervase of Howbridge,14 canon and chancellor of St Paul’s Cathedral. While the Leges Edwardi appears in the London Collection, there are no extant copies of the text which can be concretely tied to the cathedral community in the way, for example, that a twelfth-century list of St Paul's Cathedral estates in another legal collection, Corpus Christi College Cambridge MS 383, suggests that the Corpus collection of Anglo-Saxon legal material was either made at St Paul’s at the turn of the twelfth century or acquired by the community soon thereafter.15 However, such interests would certainly fit those of Gervase who was named as a key figure at St Paul’s responsible for urging the cathedral’s canons and Londoners to support Prince Louis of France against King John. He enjoyed close links to the baronial leader, Robert fitz Walter, procurator and banneret of the city of London and lord of Baynard Castle.16 It is also interesting that, given the Leges Anglorum’s interest in the Cornhill family,17 the church of St Peter upon Cornhill claimed to have been founded by Lucius as the site of the pre-Gregorian mission cathedral in London.18

Alan Smith’s study of the literary traditions surrounding King Lucius has argued that Bede’s depiction of the Augustinian mission to the Anglo-Saxons provided both form and content for Geoffrey’s expanded account of Eleutherius and Lucius.19 While Augustine continued to be depicted as chief agent of the mission to the Anglo-Saxons, the material was reworked to make Lucius central, taking the initiative and leading the narrative. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account of Lucius' conversion rendered the interpolations here into an excellent model of good, Christian kingship. In the hands of the London collector, this was further interpolated so as to offer comparison between the 'good old days' and the reign of King John.

Given the papal interdict on England from 1208 to 1213, the role of the Pope here gave further opportunity for comparison and contrast. The chosen passage of the Leges Edwardi where Pippin and his son Charles are informed that a king ought ‘to root out and eradicate and thoroughly destroy wrongdoers’ was also perhaps especially appropriate. It is reminiscent of Jeremiah 1:10, ‘See, I have set you this day over nations and over kingdoms, to root up and pull down, to destroy and overthrow, to build and to plant’, a verse whose imagery was used by Pope Innocent III (1198 – 1216) in his sermons and correspondence.20 In this vein, the Leges Anglorum interpolator expanded his materials, providing a church-sanctioned declaration of how a good Christian king ought to reign in the form of a letter purporting to have been issued by Eleutherius in reply to Lucius. Consider, for example, this statement in the text, previously noticed by J. C. Holt, that:

The king ought to reign with due observance and by the judgment of the nobles of the realm. That is to say ius and iustitia ought to reign in the realm rather than corrupt will: lex is always what makes ius, however will, violence, and force are not ius.

Debet etiam rex omnia rite facere in regno et per judicium procerum regni. Debet enim ius et iustitia magis regnare in regno quam voluntas prava: lex est semper quod ius facit voluntas vero et violentia et vis: non est ius.21

This appears directly applicable to grievances against John: that he had acted without the counsel of his barons, violently and forcefully imposing his own will.22 Comparing the statement ‘Debet iudicium rectum in regno facere et iusticiam per consilium procerum regni sui tenere’ in Pope Eleutherius’ letter with the more common reference to the ‘consilium baronum, episcoporum, etc.’, Walter Ullmann suggested that the phrase consilium regni may have found its way into Clause 12 of Magna Carta from this account.23 This statement is part of a larger descriptive account of the coronation oath which has been interpolated into the Leges Edwardi. While it is not part of the oath used in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Liebermann noted that the Leges Anglorum’s statement does appear in a French account of Edward I's coronation oath. Given its appearance in the Leges Anglorum, the impetus for the inclusion of consilium regni in the oath may have existed since at least this period.24 It is also intriguing that the papal rescript for Lucius appears to posit ‘iusticiam per consilium procerum regni’ as the more appropriate alternative to the Roman and imperial laws (leges Romanas et Caesaris) which Lucius had sought from the pope.25

As a further admonition and critique of current events, Eleutherius' letter is prefaced with the following:

He ought to consider everything in advance and this is the king's because ‘anger manages everything badly’, according to the Gospel, ‘every kingdom divided against itself will be forsaken’.

Omnia debet premeditari et hoc regis est quia male cuncta ministrat impetus. Iuxta euangelium omne regnum in seipsum diuisum desolabitur. Hec actenus.26

A quotation from Statius' Thebaid27 is paired with the verse from the Gospel of Luke, ‘Every kingdom divided against itself shall be brought to desolation; and house upon house shall fall’ (Luke 11:17). This is a common comparison in chronicles, and Richard of Devizes used the same imagery of Oedipus' sons in his Chronica when discussing the Angevin dynasty and the complications of shared rule and alternating kingship in the context of Richard I and John.28 Both seemingly make reference to the issues related to the instability in the realm while Richard was absent from England. Orderic Vitalis had used the same metaphor for the discordia cause by Robert of Normandy and Henry I. Statius was a popular work, copies were made at Carolingian Corbie and his works, except the Silvae, were copied regularly in the twelfth century.29 It circulated widely alongside commentary by Lactantius Placidus, and, as Statius was considered one of the Pagan authorities on morals and ethics, the medieval tradition of the Thebaid saw the text as a model to instruct rulers on good governance.30 Within the context of the Leges Anglorum more broadly, this allusion alongside Pope Eleutherius' letter provides building blocks for the ideology of kingship being constructed by the compiler. The allusion may have been picked up directly from Richard of Devizes or developed independently via the wide circulation of the Thebaid itself or within the context of more 'popular' texts like the Old French Roman de Thèbes.

In the Leges Anglorum, the interpolated letter of Pope Eleutherius is but one example of how the editorial choices of the compiler built a case against unjust kingship. Articulated through the statement of established laws and customs, such kingship was deemed unjust because it functioned without due forms of consent. In a similar vein, the compilation’s version of the Leges Henrici Primi is also adapted to emphasise the importance of the lex terre and the iudicium curie over the king’s will:

For nothing from anyone ought to be exacted or taken except by right and reason, according to the law of the land and justice and according the judgement of the court without deceit, just as was established with the greatest consideration of the noble and good predecessors of the whole realm and by the assiduous aggregation of the servants of God and approved by the good and wise of the whole kingdom.

Quia ni(hi)l a nullo exigi uel capi debe(a)t nisi de iure et ratione, per legem terre et iustitiam et per iudicium curie sine dolo, prout statutum est maxima consideratione procerum et bonorum predecessorum tocius regni et multa aggregacione seruorum Dei et bonorum partum et sapientum tocius monarchie approbatum.31

Like Eleutherius’ letter to Lucius, the copy of Prester John’s letter which appears later in the compilation32 seems to have been inserted as a further depiction of good Christian kingship and of a well-ordered, powerful kingdom. As such, it was intended to rebuke the pretentions of England's King John and to offer an aspirational model for the kingdom. Derek Keene has highlighted the fact that the repetition of specific genres and themes in the compilation’s components organises the compilation, with such repetition providing structural continuity to the compilation as a narrative. 33 The Leges Anglorum’s thematic structure reflects how London’s interests were pursued by its elite and understood within a broader historical and geographical context representative of the kingdom. For example, the inclusion in the Leges Edwardi of Pope Eleutherius' letter (Rs, f. 58r) and the quoted and attributed description of Britain from the Historia regum Britannie (Rs, f. 70r) parallel the inclusion later in the Leges Anglorum compilation of Prester John’s letter (Ai, f. 92r) and a French language description of Britain derived from Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum i.1-8 (Ai, f. 101r).

The vast wealth described in the marvellous description of Prester John’s kingdom was perhaps deliberately framed in contrast both to the extensive taxation undertaken in England and to the contraction of King John’s continental holdings. The utopian depiction of this foreign Christian kingdom enjoyed widespread popularity in the twelfth century, as described by Michael Uebel: ‘To the internecine strife characteristic of the twelfth-century political environment, the figure of Prester John offers an alternative: a society under the control of a Priest-King, who alone ... acts as the mythic guarantor of the order of things’.34 If its value as utopian literature contributed to its popularity, its depiction of a vast and peaceful kingdom ruled by a good Christian king could find continued relevance in early thirteenth-century England.

Extended account in Version 4 of the Leges Edwardi Confessoris on the law and appendages to the crown of the kingdom of Britain and what the king’s office is (c. 11, 1A) and Pope Eleutherius’ Letter to King Lucius (c. 11, 1B).

Rs = Manchester, John Rylands Library, Latin MS 155, ff. 57r-58v

K = London, British Library, Cotton MS Claudius D II, ff. 32rb-33rb

Or = Oxford, Oriel College MS 46, ff. 30rb-31ra

Co = Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 70, pp. 57-59.

Printed Edition Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen (3 vols., Halle, 1903-1916), i, pp. 635-637. Printed below from Rs.

De iure et de appendiciis corone regni Britannie et quod sit officium regis.

R35ex autem, quia uicarius summi regis est, ad hoc est constitutus: ut regnum terrenum et populum domini et super omnia sanctam eius ueneretur ecclesiam et regat et ab iniuriosis defendat et maleficos36 ab ea euellat et destruat et penitus disperdat. Quod nisi fecerit, nec37 nomen regis nomen38 in eo constabit, uerum papa Iohanne testante nomen regis perdit, cui Pinpinnus et Karolus filius eius, necdum reges set39 principes sub rege Francorum stulto, scripserunt querentes si ita permanere deberent Francorum reges, solo regio nomine contenti. A quo responsum est: ‘Illos decet uocari reges qui uigilanter defendunt et regunt ecclesiam Dei et populum eius’, imitati40 regem psalmigraphum dicentem: ‘Non habitabit in medio domus mee qui facit superbiam et cetera’ (Psalms 100:7).

Debet uero rex de iure41 omnes terras et honores et42 omnes dignitates et iura et libertates corone regni huius in integrum cum omni integritate et sine diminucione obseruare et defendere, dispersa et delapidata43 et ammissa44 regni iura in pristinum statum et debitum uiribus omnibus reuocare. Uniuersa uero terra et tota et insule omnes Occidentalis Occeani45 usque Norwegiam et usque Daciam pertinent ad coronam regni huius46 et sunt de appendiciis et de47 dignitate regis et regni48, et una est monarchia et unum est regnum, et uocabatur49 quondam regnum Britannie, modo enim uocatur regnum Anglorum. Tales enim metas et fines ut predicte sunt constituit et imposuit corone regni huius d50ominus Eleutherius51 papa sentencia sua, anno scilicet52 sexagesimo53 septimo post passionem Christi, qui primo destinauit coronam benedictam Britannie et Christianitatem, Deo inspirante, Lucio regi Britonum54. Debet eciam rex omnia rite facere in regno et per iudicium procerum regni. Debet enim ius et iusticia magis regnare in regno quam uoluntas praua: lex est semper quod ius facit55, uoluntas enim et uiolentia et uis non est ius. Debet uero rex Deum timere super omnia et diligere et mandata eius per totum regnum suum seruare. Debet eciam sanctam ecclesiam regni sui cum omni integritate et libertate iuxta constituciones patrum et predecessorum seruare, fouere, manutenere, regere et contra inimicos defendere, ita ut Deus pre ceteris honoretur et pre occulis56 semper habeatur. Debet eciam bonas leges et consuetudines approbatas erigere, prauas autem delere et omnino a regno deponere. Debet iudicium rectum in regno facere et iusticiam per consilium procerum regni sui tenere. Ista debet uero57 omnia rex in propria persona, inspectis et tactis sacrosanctis euangeliis58 et super sacras et sanctas reliquias coram regno et sacerdocio et clero iurare antequam ab archiepiscopis et ab59 episcopis regni coronetur. Tres enim rex habere debet seruos60: luxuriam, auariciam et cupiditatem, quos si habuerit seruos, bene et illustre in suo61 regnabit regno. Omnia debet premeditari et hoc regis est. Quia ‘male cuncta ministrat impetus’ (Statius, Thebaid X, 704-705), iuxta Euangelium62, ‘omne regnum in seipsum diuisum desolabitur63’ (Luke 11:17). Hec actenus.64

On the law and the appendages to the crown of the kingdom of Britain and what the king’s office is.

The king, moreover, because he is the vicar of the highest king, was established for this: to honour and rule the earthly kingdom and the people of the Lord and above all else his holy church and to defend it from injury and to root out and eradicate and thoroughly destroy wrongdoers. Unless he does, the name ‘king’ will not agree with him and he loses the name ‘king’, as Pope John testifies, to whom Pippin and his son Charles, not yet kings but princes under the foolish king of the Franks, wrote asking if those content with only the name ‘king’ ought to remain kings of the Franks. To which was answered: ‘Those ought to be called ‘kings’ who vigilantly defend and rule the church of God and his people’, echoing the royal psalmist’s saying: ‘He who works pride will not dwell in the midst of my house etc.’ (Psalms 100:7).

Truly, the king ought to observe and defend, according to law, all lands and honours and all dignities and rights and freedoms of the crown of this kingdom in its entirety with all integrity and without abatement, to restore the kingdom's scattered and dispersed and lost laws to a pristine state and what is owed to all men. Truly, the universal and whole land and every island of the Western Sea all the way to Norway and all the way to Denmark pertain to the crown of this kingdom, and are of the appendages and dignity of the king and the kingdom, and is one monarchy and one kingdom, and was formerly called the kingdom of Britain, presently called the kingdom of the English. For such constitutes and establishes the metes and bounds, as are previously named, of the crown of this kingdom [wrote]65 the lord Pope Eleutherius, with his sentence, who in the sixty-seventh year after Christ’s passion first addressed the blessed crown of Britain and Christianity, by the inspiration of God, Lucius king of the Britons. Furthermore, the king ought to reign with due observance and by the judgment of the nobles of the realm. That is to say ius and iustitia ought to reign in the realm rather than corrupt will: lex is always what makes ius, for will, that is violence and force, is not ius. Truly, the king ought to fear and hold a special regard for God above all else and to preserve his mandates throughout his entire kingdom. Additionally, he ought to serve, maintain, preserve, rule and defend against all enemies the holy church of his kingdom with all integrity and freedom according to the constitutions of his fathers and predecessors, so that God is honoured before all others and is always before his eyes. Additionally, he ought to encourage good laws and appropriate customs, while expunging from the kingdom and dismantling altogether the false ones. He ought to make just judgements in the kingdom and maintain justice by the advice of the nobles of his kingdom. This in all respects the king ought personally to swear upon the sacred and holy relics before the kingdom and priesthood and clergy, the sacred holy gospels having been inspected and touched, before he is crowned by the archbishops and bishops of the kingdom. The king ought to have three slaves: luxury, avarice and lust, which if he holds as slaves he will reign well and illustriously in his kingdom. He ought to consider everything in advance and this is the king's because ‘anger manages everything badly’ (Statius, Thebaid X, 704-705), according to the Gospel, ‘every kingdom divided against itself will be forsaken’ (Luke 11:17). This is sufficient.

Epistola domini Eleutherii pape66 Lucio regi Britannie.

A67nno [centesimo]68 sexagesimo nono a passione Christi scripsit dominus Eletherius69 papa 70 Lucio regi Britonum71 ad correctionem72 regis et procerum regni Britannie: Pecistis a nobis leges Romanas et Cesaris uobis transmitti, quibus in regno Britannie uti uoluistis. Leges Romanas et Cesaris semper reprobare possumus, legem Dei nequaquam. Suscepistis enim nuper miseratione diuina in regno Britannie legem et fidem Christi, habetis penes uos in regno utramque paginam, ex illis Dei gratia per consilium regni uestri sume legem, et per illam Dei73 paciencia uestrum rege Britannie regnum. Uicarius uero Dei estis in regno iuxta psalmisatm regem: ‘Domini est terra et plenitudo eius orbis terrarum et uniuersi qui habitant in eo’ (Psalms 23:1), et rursum iuxta psalmistam regem: ‘Dilexisti iusticiam et odisti iniquitatem, propterea u[n]74xit75 te Deus, Deus tuus oleo leticie pre consortibus tuis76’ (Psalms 44:8). Et rursum iuxta psalmistam regem: ‘Deus iudicium tuum regi da et iusticiam tuam filio regis77’ (Psalms 71:2). Non enim dixit78 iudicium neque iusticiam Cesaris. Filij enim regis gentes Christiane et populi regni sunt, qui sub uestra79 protectione et pace in80 regno degunt et consistunt. Iuxta Euangelium81: ‘Quemadmodum gallina congregat pullos sub alis’ (Matthew 23:37). Gentes uero regni Britannie et populi pulli82 uestri sunt, 83 quos diuisos debetis in unum et84 concordiam et pacem et ad fidem et 85 legem Christi et ad sanctam ecclesiam congregare, reuocare, fouere, manutenere, protegere, regere et ab iniuriosis et malificis86 et 87 inimicis semper defendere. ‘[D] 88e regno, cuius rex puer est, et cuius principes mane comedunt89’ (Ecclesiastes 10:16), non uoco regem, propter paruam et 90 minimam etatem, set propter stulticiam et iniquitatem et insanitatem. Iuxta psalmistam regem: ‘Uiri sanguinum et dolosi non dimidiabunt91 dies suos et cetera’ (Psalms 54:24). Per commestionem intelligimus gulam, per gulam luxuriam, per luxuriam omnia turpia et peruersa et mala, iuxta Salomonem regem: ‘In maliuolam animam non introibit sapiencia nec habitabit in corpore subdito peccatis92’ (Wisdom 1:4). Rex dicitur a regendo, non a regno. Rex eris dum bene regis, quod nisi feceris, nec93 nomen regis 94 nomen95 in te constabit, et nomen regis perdes, quod absit. Det uobis omnipotens Deus regnum Britannie sic regere ut possitis cum Eo regnare in eternum, cuius uicarius estis in regno predicto, qui cum Patre et Filio et Spiritu Sancto uiuit et regnat Deus per infinita seculorum secula96. Hec actenus.97

The letter of the lord Pope Eleutherius to Lucius, king of Britain.

[One hundred and] sixty-nine years after Christ’s passion, the lord Pope Eleutherius wrote to Lucius, king of the Britons, for the correction of the king and the nobility of the kingdom of Britain: You asked us to send to you Roman and imperial law which you wished to use in the kingdom of Britain. The Roman and imperial laws we can always reject. God’s law we can by no means reject. Indeed you have recently received by divine mercy the law and faith of Christ in the kingdom of Britain. You hold under your control in your kingdom both scriptures [pagina]; from those by God’s grace, obtain law in accordance with the counsel of your kingdom and in accordance with that, by God’s patience, rule your kingdom of Britain. You are the vicar of the true God in the kingdom. According to the psalmist king: ‘The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness of it the world and all those who inhabit it’ (Psalms 23:1). And again according to the psalmist king: ‘You have loved righteousness and hated iniquity therefore God your lord has anointed you, your God with the oil of gladness above your associates’ (Psalms 44:8). And again according to the psalmist king: ‘O God give the king your judgment and your justice to the king’s son’ (Psalms 71:2). Indeed he did not say the judgment or justice of the emperor [iusticia Cesaris]. Indeed the king's sons and the people of the kingdom are Christian people who under your protection and peace carry on and remain in the kingdom. According to the gospel: ‘In the same way that a hen gathers [her] chicks beneath her’ (Matthew 23:37). Truly, the gentes and people of the kingdom of Britain are your chicks whom if divided you ought to bring together as one in concord and peace to the faith and law of Christ and to the holy church, to revive, to cherish, to hold by the hand, to protect, to reign and always to defend from injustices and evil things and enemies. Concerning the kingdom ‘whose king is a boy and whose princes eat in the morning’ (Ecclesiastes 10:16), I do not call him king because of his small and minimum age but also because of his stupidity and iniquity and unsoundness. According to the psalmist-king: ‘Men of blood and deceit halve their days etc.’ (Psalms 54:24). By consuming we understand appetite; by appetite luxury, by luxury all disgrace and perversion and ill. According to King Solomon: ‘Wisdom will not enter a malevolent spirit nor live in a body subordinated by sin’ (Wisdom 1:4). One is called king by ruling, not by a kingdom. You will be king while you rule well, but if you do not do this the name ‘king’ will not agree with you and you will lose the name ‘king’, God forbid. Omnipotent God grant you the kingdom of Britain so to rule in order that you may reign with Him in eternity, whose vicar you are in the aforementioned kingdom, who with the Father and Son and Holy Spirit lives and reigns God for infinite ages of ages. This is sufficient.

1 | I would like to thank Mary Blanchard, Kenneth Duggan, and Nicholas Vincent for their comments on earlier versions of this text and George Garnett for his comments on the same and on portions of my doctoral thesis from which this was derived. |

2 | Translation from B. R. O’Brien, God’s Peace and King’s Peace (Philadelphia, 1999), pp. 174-175 [c. 17]. |

3 | The Leges Edwardi has mistakenly attributed this to a Pope John. However, according to Ado of Vienne’s Chronicon this should be Pope Zacharias (r. 741-752). (O’Brien, p. 175, n. 59.) |

4 | Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, ed. B. Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors (Oxford Medieval Texts, Oxford, 1969), 1.iv, n. 2; J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People: A Historical Commentary (Oxford Medieval Texts, Oxford, 1988), p. 11. |

5 | The Book of Pontiffs (Liber Pontificalis): The Ancient Biographies of the first Ninety Roman bishops to AD 715, ed. R. Davis (3rd edn., Liverpool, 2010), pp. 5-6. |

6 | The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, trans. B. Colgrave, ed. J. McClure and R. Collins (Oxford, 2008), p. xxvi. |

7 | Nennius, Historia Britonum: The History of the Britons, ed. R. Rowley (Lampeter, 2005), pp. 26-27. |

8 | Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the kings of Britain: An edition of De gestis Britonum (Historia regum Britanniae), ed. M. D. Reeve, trans. N. Wright (Woodbridge, 2007), iv.72. |

9 | J. Scott, The Early History of Glastonbury: An Edition, Translation and Study of William of Malmesbury’s ‘De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesie’ (Woodbridge, 1981), pp. 47-51. |

10 | Geoffrey of Monmouth, iv.72. |

11 | Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, Book IX, iii, 4. [PL 82.342]; John of Salisbury, Policraticus: of the frivolities of courtiers and the footprints of philosophers, trans. C. J. Nederman (Cambridge, 1990), p. 193 [Book viii]; Gerald of Wales, De Principis Instructione in Giraldi Cambrensis Opera, ed. J. S. Brewer, J. F. Dimock, G. F. Warner (8 vols., Rolls Series 21, 1861-1891), viii, p. 54; J. C. Holt, Magna Carta, rev. by G. Garnett and J. Hudson (3rd edn., Cambridge, 2015), p. 99; W. Parsons, ‘The Mediaeval Theory of the Tyrant’, The Review of Politics 4 (1942), pp. 129-143; |

12 | On the relationship between the two authorial versions and two subsequent revisions see O’Brien, pp. 137-138, Appendix (pp. 205-206). |

13 | The production of three later manuscripts have been connected with Andrew Horn, city chamberlain in London from 1320 to 1328, which are currently held in parts across three institutions: Manuscript 2: Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 70 + 258; Manuscript 3: London Guildhall MS Liber Custumarum, ff. 103-72, 187-284 + Oxford, Oriel College MS 46, ff. 1-108 + BL Cotton MS Claudius D II, ff. 116-123; and Manuscript 4: Liber Custumarum, ff. 1-102, 173-86 + BL Cotton MS Claudius D II, ff. 1-24, 30-40, 42-115, 124-35, 266-77 + Oriel College MS 46, ff. 109-211. (N. R. Ker, ‘Liber Custumarum, and Other Manuscripts Formerly at the Guildhall’, Guildhall Miscellany, 3 (1954), pp. 37-43.) |

14 | Magna Carta (London, 2015), p. 278 |

15 | P. Wormald, The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, I: Legislation and its Limits (Oxford, 2001), pp. 230-234. Codicological and palaeographic evidence suggests that St Paul's as the site of the manuscript's production may be more tenuous than generally considered. (T. J. Gobbitt, The Production and Use of MS Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 383 in the Late Eleventh and First Half of the Twelfth Centuries (University of Leeds PhD Thesis, 2010), pp. 48-64. |

16 | L’Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), p. 171-172 ; Holt, pp. 20-23, 244; London 1189-1228, ed. D. P. Johnson (English Episcopal Acta 26, 2003), p. lvii; Rotuli litterarum clausarum in turri Londoniensi asservati, ed. T. Duffus Hardy (2 vols., London, 1833-4), i, p. 165b. |

17 | While the interest manifests itself a few times through the compilation, it is clearest in the inclusion of a genealogy listing various members of the Cornhill family, through the three sons of Hubert of Caen: Alan, Gervase, and William Blemund. (Ai, f. 127v) |

18 | The most thorough discussion of this claim is to be found in J. Clark, ‘The King Lucius tabula in St Peter Upon Cornhill church, London’, April 2014, https://www.academia.edu/6553953/The_King_Lucius_tabula_in_St_Peter_Upon_Cornhill_church_London. |

19 | Bede, 1.xxiii; A. Smith, ‘Lucius of Britain: Alleged King and Church Founder’, Folklore 90 (1979), pp. 29-36, at pp. 34-35. |

20 | The sermon is the one associated with his consecration (Sermo III. In Consecratione Pontificis in Patrologia Latina [PL] 217: 653-660) and examples in Innocent III’s correspondence from the first five years of his papacy: PL 214:319-320 (no. CCCXLV), PL 214:356 (no. CCCLXXVI), 214:391-392 (no. CCCCXIII), 214:481 (no. DXXV), 214:481-482 (no. DXXVI), 214:750-751 (no. CCII), 214:903-906 (no. XIV), 214:977-979 (no. XXVI), 214:979-980 (no. XVII). For discussion and further examples see: J. C. Moore, Pope Innocent III (1160/61-1216): To Root up and to Plant (Leiden, 2003), pp. 26-30, 126-129, 183-184, 215, 217, 256, 264-277. |

21 | Rs, f. 57v. |

22 | Holt, pp. 102-103. |

23 | ‘On the influence of Geoffrey of Monmouth in English History’, in Speculum Historiale: Geschichte im Spiegel von Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtsdeutung Johannes Spörl dargebracht, ed. C. Bauer, L. Böhm and R. Müller (Freiburg, 1965), pp. 258-263, at p. 261. |

24 | F. Liebermann, Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen (3 vols., Halle, 1903-1916), i, p. 635. |

25 | Ullmann, p. 261; Liebermann, Über die Leges Anglorum saeculo XIII. Ineunte Londoniis collectae (Halle, 1894), p. 42. |

26 | Leges Edwardi, c. 11, 1 A 10. |

27 | Statius, Thebaid, X.704-705. |

28 | J. Martindale, 'Perceptions of the Angevin Dynasty', unpublished. (IHR Earlier Middle Ages Seminar, 20 November 2013). |

29 | L. D. Reynolds and N. G. Wilson, Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature (4th edn., Oxford, 2013), pp. 99, 113. |

30 | D. Battles, The Medieval Tradition of Thebes: History and Narrative in the OF Roman de Thèbes, Boccaccio, Chaucer, and Lydgate (London, 2004), pp. 2, 6. |

31 | Rs, f. 84r. This passage was previously pointed out by Ullmann in his Principles of Government and Politics in the Middle Ages (London, 1961), p. 165. |

32 | Ai, ff. 92r-97v. The text found in the Leges Anglorum is complete except for the last four sections (§97-100), which were not included, and is part of recension B, which is distinguished from earlier versions by its inclusion of an expanded account of the pepper forest and a long description of Prester John’s second palace. (B. Wagner, Die ‘Epistola presbiteri Johannis’, lateinisch und deutsch: Überlieferung, Textgeschichte, Rezeption und Übertragungen im Mittelalter (Tübingen, 2000), p. 167.) |

33 | ‘Text, Visualisation and Politics: London, 1150-1250’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 6th series, 18 (2008), pp. 69-99, esp. at p. 84. |

34 | Ecstatic Transformation: On the Uses of Alterity in the Middle Ages (Basingstoke, 2005), p. 95. |

35 | R: Omitted [for decorated capital] Or |

36 | maleficos: Gap [scraped away text before next word which begins on a new line] K |

37 | nec: Omitted Or Co |

38 | nomen: non K Or Co |

39 | set: sed Or Co |

40 | imitati: imitatis K Co |

41 | rex de iure: de iure rex K Or Co |

42 | et: Omitted K Or Co |

43 | delapidata: dilapidata K Or Co |

44 | ammissa: amissa Or Co |

45 | Occidentalis Occeani: omnes K Omitted Or Co |

46 | huius: eius K Or Co |

47 | de: Omitted K Or |

48 | et regni: Omitted K Or Co |

49 | uocabatur: uocabitur K |

50 | D: Omitted [for decorated capital] Or |

51 | Eleuterius: Euletherius K Co |

52 | scilicet: Omitted Co |

53 | centesimo [Interlinear addition in later hand] K |

54 | Britonum: Bretorum K Or Co |

55 | facit: faciat K Or Co |

56 | occulis: oculis K |

57 | debet uero: uero debet Or Co |

58 | euangeliis: ewangeliis Or Co |

59 | ab: Omitted Or Co |

60 | debet seruos: seruos debet scilicet K Co seruos debet Or |

61 | in suos: Omitted K Or Co |

62 | Euangelium: Ewangelium K |

63 | desolabitur: Omitted K Co |

64 | actenus: hactenus K Co |

65 | Potential word missing from original text, follows use of scripsit in the opening of the following section. |

66 | Eleutherii pape: Euletherii K Co |

67 | A: Omitted [for decorated capital] Or |

68 | Omitted Rs |

69 | Eleutherius: Euletherius K Co |

70 | a K |

71 | Britonum: Britannie K Or Co |

72 | correctionem: porectionem Co |

73 | Dei: de Or |

74 | Omitted Rs |

75 | odisti iniquitatem, propterea unxit: o. i pp. u. K Or Co |

76 | oleo leticie pre consortibus tuis: o. l. p. co. te. K Or Co |

77 | regi da et iusticiam tuam filio regis: et cetera K Or Co |

78 | dixit: Omitted Or Co |

79 | uestra: nostra K Or Co |

80 | in: et Or Co |

81 | Euangelium: Ewangelium K Or Co |

82 | pulli: Omitted Or Co |

83 | et Or |

84 | et: ad K Or Co |

85 | ad Or Co |

86 | malificis: maliciosis K Co |

87 | ab Co |

88 | U Rs K Co Omitted [for decorated capital] Or |

89 | comedunt: commedunt K Co |

90 | aut Or |

91 | dimidiabunt: dimidicabunt K dimiciabunt Or |

92 | nec habitabit in corpore subdito peccatis: Add in the margin Rs |

93 | nec: Omitted K Or Co |

94 | et Or |

95 | nomen: non K Co |

96 | et Filio et Spiritu Sancto uiuit et regnat Deus per infinita seculorum secula: et cetera K Or Co |

97 | Hec actenus: Omitted K Or Co |

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265