The Magna Carta of Cheshire

May 2015,

Cheshire Local History Association, the umbrella organisation for the local history and heritage societies within the bounds of the former county palatine, has recently published The Magna Carta of Cheshire as its contribution to the 800th anniversary. This was a charter of liberties issued by Ranulf III earl of Chester, almost certainly in 1215, as a local counterpart to that granted by King John at Runnymede.

The booklet, which runs to just over 100 pages, includes both the Latin text of the charter and an English translation by Jonathan Pepler, chairman of the Association and former County Archivist. It also offers a detailed commentary by Graeme White, Emeritus Professor of Local History at the University of Chester and editor of the Association’s journal, Cheshire History. In the Feature which follows, Professor White provides a summary of the context and content of Earl Ranulf’s great charter, along with a copy of the translation.

On 30 March 1300, two days after the formal reissue of Magna Carta for what would be the last time, King Edward I confirmed a charter of liberties for Cheshire. He had been granted lordship of the county at the age of fourteen in 1254 and would go on, in 1301, to confer it upon his sixteen-year-old heir, this time with the title of earl. Edward had confirmed this charter once before, in the aftermath of his victory at the battle of Evesham, rewarding the community of Cheshire for its support in the perilous conflict and signalling the recovery of the county after a few months formally in the custody of Simon de Montfort.1 That confirmation had been dated 27 August 1265, some weeks after his father, King Henry III, had been coerced into reaffirming the 1225 Magna Carta at the height of baronial rebellion the previous March. So we have two confirmations by Edward for Cheshire, both closely associated in time with renewals of Magna Carta.

What of the original charter of liberties, with which Edward was evidently so concerned to identify himself? This charter, too, can be linked to Magna Carta, so much so that it is often dubbed the Magna Carta of Cheshire.2 Granted by the early-thirteenth-century earl of Chester, Ranulf III (Ranulf de Blundeville), it certainly bore a resemblance to the product of the Runnymede negotiations of June 1215, with the same concern to protect the interests of heirs and widows and an insistence that the beneficiaries should pass on the concessions to their own free men and tenants. The Cheshire charter also dates, significantly, to the closing phase of John’s reign, the outside limits being 4 March 1215, when the earl took the cross - an event alluded to in the document - and 19 October 1216, the king’s death, by which time one of the witnesses, Hugh de Pascy, had been killed.3 But there were important differences from the Runnymede Magna Carta as well. They tell us much about the exceptional status of Cheshire at this time, and about the aspirations of leading landholders in a relatively-poor and under-populated frontier county.

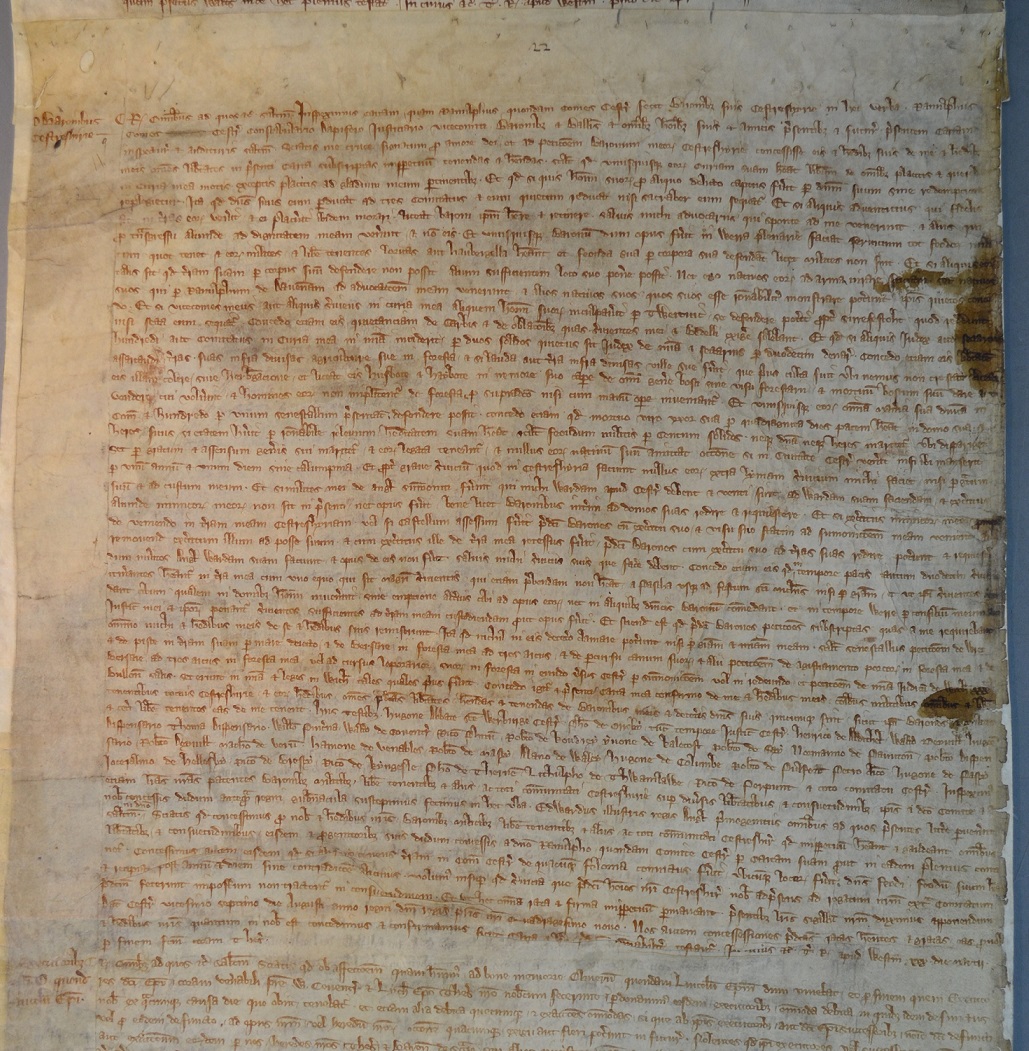

The 1300 confirmation of the Cheshire charter is preserved in a Patent Roll (TNA C66/120 m. 22) as an enrolled copy of an inspeximus, which provides us with the earliest surviving version of Earl Ranulf’s text. After reciting the earl’s charter, the roll refers briefly to Edward’s previous confirmation of 1265, adding further concessions made to the men of Cheshire on that occasion but treating them as distinct from the original charter. This offers reassurance that the text which has come down to us from 1300 is an accurate rendering of what Earl Ranulf actually granted: the community of Cheshire was adept at seeking further liberties - as it also did in 1249 with demands such as limits on penalties and the fixing of the justiciar’s court at Chester, both conceded by Henry III4 - but it did not try to intrude them into the clauses of the charter. A seventeenth-century transcription of the charter by the Cheshire antiquarian Randle Holme, who claimed to be basing it upon two sealed originals in front of him, is identical to the inspeximus text of 1300 save for minor variations of spelling.5

By the close of the twelfth century, Cheshire enjoyed considerable administrative autonomy and was clearly developing a separatist tradition. It would be almost another hundred years before we have evidence of its being described as a ‘palatinate’, but arrangements ultimately derived from William the Conqueror’s dispositions along the Welsh marches meant that there was no royal demesne in Cheshire, no taxes were levied here for the king and no itinerant justices crossed into the county. Until Cheshire was effectively annexed by the crown when the male line of Anglo-Norman earls died out in 1237, the county was consistently absent from the pipe rolls, except for the periods when Earls Hugh II and Ranulf III were minors and hence wards of King Henry II.6 In the 1190s, Lucian, a monk of St Werburgh’s abbey, Chester, described Cheshire as a ’province’ (provincia) separated from the rest of England by the wooded Lyme, an upland area identifiable today by such place-names as Audlem, Newcastle-under-Lyme and Ashton-under-Lyne, roughly corresponding to the county’s borders with Shropshire, Staffordshire, Derbyshire and Lancashire. Within this province, he wrote, ‘both by royal permission and by the virtues of its earls, Cheshire answers in its assemblies more to the sword of its prince than the crown of the king’.7 Indeed, it is clear from Ranulf III’s charters, including his so-called ‘Magna Carta’ for the county, that ‘pleas of the sword’ reserved to the jurisdiction of the earl or (usually, in practice) his justiciar of Chester, were deemed equivalent to ‘pleas of the crown’ elsewhere in the kingdom.8 Although there was to be nothing in King John’s Magna Carta specifically excluding Cheshire from its provisions, there was evidently a sufficiently-strong sense of independence among the county’s politically-aware elite to make the issue of a separate document a feasible proposition.

Ranulf III had succeeded to the earldom of Chester in 1181, attaining his majority in 1187. By the end of Richard I’s reign he was the richest of all the Anglo-Norman barons after the king’s brother John, with an estate which gave him a strategically-important geopolitical position across the Midlands and north of England, besides his continental holdings. The loss of his interests in Brittany and Normandy between 1199 and 1204 cost him heavily and (like many others) he was not fully trusted by King John. Nevertheless, he remained loyal, never more so than in the crisis of 1214-16 when he participated in the Poitou campaign and helped negotiate the concluding truce, was with the king on several occasions in the months before and after June 1215 (though apparently not at Runnymede itself) and played a leading role on the royalist side in the civil war. After John’s death in October 1216, he was a prominent member of the group of the late king’s executors which decided to reissue Magna Carta in the name of the boy-king Henry III. Thereafter, his continued campaigning helped to bring the war to a successful conclusion the following September, when he was among those ratifying the peace agreement. His subsequent career, as crusader, castle-builder and ally of Llywelyn prince of Gwynedd, revealed an independence of purpose which often set him at odds with Henry III’s government but never tipped him into open rebellion.9

We know very little about Ranulf’s charter for Cheshire other than what can be gleaned from the document itself. There is no reference to it, for example, in the annals of Chester abbey, a useful source for local events, nor in any of the roughly-contemporary accounts of national affairs. As the charter makes clear, it was granted at a meeting of the county court in Chester castle in response to petitions submitted by the Cheshire barons, some of which the earl turned down. The whole exercise seems to have been conducted in muted fashion: the Cheshire barons could be counted on two hands10 and there is no hint of any armed confrontation. Within the dating limits already set out, it is not impossible that Ranulf’s charter precedes the grant of the Runnymede Magna Carta. However, it most probably belongs to the weeks following June 1215, prompted by the spectacle of copies of the king’s concessions being distributed across the kingdom and inquests being held into abuses committed by local officials. If so, it may be regarded as the first in a series of declarations of laws, customs or principles down the centuries, allegedly inspired - to a greater or lesser extent - by Magna Carta.

Such evidence as we have strongly suggests that no official copy of the 1215 Magna Carta reached Cheshire; it was not among the counties for which sealed copies were intended, as they appear on a list of those sent out in late June and July.11 However, the county’s barons were far from isolated from national affairs, since they held land elsewhere in the kingdom. Among their number was John de Lacy lord of Halton, a major tenant-in-chief and one of the ‘Twenty-Five’ of Magna Carta clause 61.12 So there may well have been an impression among the leading landholders of Cheshire that their county was ‘missing out’. If so, a date for the Cheshire charter in August or September 1215 is plausible. For the duration of the civil war, from autumn 1215 onwards, Earl Ranulf was rarely in Cheshire with an opportunity to meet his barons in the county court. But the late summer would have given time for petitions to be formulated and considered, while focusing the minds of earl and barons alike on the need to reach a settlement before the inevitable conflict began. Clause 10 of the charter, for example, reads like an agreement on what might imminently be required of the Cheshire barons in providing military support to their lord.

The Latin text which follows is reproduced by courtesy of the Council of the Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire from Charters of the Anglo-Norman Earls of Chester, c.1071-1237, ed. G. Barraclough, Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, CXXVI, 1988, no. 394, pp. 388-91, where notes are provided on minor textual differences between the various copies. Barraclough based his text primarily on Randle Holme’s seventeenth-century transcription.

Ranulfus comes Cestrie constabulario, dapifero, iusticiario, vicecomiti, baronibus et ballivis et omnibus hominibus suis et amicis presentibus et futuris presentem cartam inspecturis et audituris salutem. Sciatis me cruce signatum pro amore dei et ad peticionem baronum meorum Cestresirie concessisse eis et heredibus suis de me et heredibus meis omnes libertates in presenti carta subscriptas in perpetuum tenendas et habendas, scilicet:

1. Quod unusquisque eorum curiam suam habeat liberam de omnibus placitis et querelis in curia mea motis exceptis placitis ad gladium meum pertinentibus, et quod si quis hominum suorum pro aliquo delicto captus fuerit, per dominum suum sine redemptione replegietur, ita quod dominus suus eum perducat ad tres comitatus et eum quietum reducat, nisi sacraber eum sequatur.

2. Et si aliquis adventitius, qui fidelis sit, in terris eorum venerit et ei placuerit ibidem morari, liceat baroni ipsum habere et retinere, salvis mihi advocariis qui sponte ad me venerint et aliis qui pro transgressu aliunde ad dignitatem meam venerint, et non eis.

3. Et unusquisque baronum, dum opus fuerit, in werra plenarie faciat servicium tot feodorum militum quot tenet, et eorum milites et libere tenentes loricas aut haubergella habeant et feoda sua per corpora sua defendant, licet milites non sint. Et si aliquis eorum talis sit quod terram suam per corpus suum defendere non possit, alium sufficientem loco suo ponere possit. Nec ego nativos eorum ad arma iurare faciam, sed nativos suos, qui per Ranulfum de Davenham ad advocationem meam venerunt, et alios nativos suos, quos suos esse rationabiliter monstrare poterunt, ipsis quietos concedo.

4. Et si vicecomes meus aut aliquis serviens in curia mea aliquem hominum suorum inculpaverit, per thwertnic se defendere poterit propter sirevestoth quod reddunt, nisi secta eum sequatur.

5. Concedo etiam eis quietanciam de garbis et de oblacionibus, quas servientes mei et bedelli exigere solebant. Et quod si aliquis iudex aut sectarius hundredi aut comitatus in curia mea in misericordia inciderit, per duos solidos quietus sit iudex de misericordia et sectarius per duodecim denarios.

6. Concedo etiam eis libertatem assartandi terras suas infra divisas agriculture sue in foresta, et si landa aut terra infra divisas ville sue fuerit, que prius culta fuit, ibi nemus non crescat, liceat eis illam colere sine herbergacione, et liceat eis husbote et haybote in nemore suo capere de omni genere bosci sine visu forestarii, et mortuum boscum suum dare aut vendere cui voluerint. Et homines eorum non implacitentur de foresta pro supradicto, nisi cum manuopere inveniantur.

7. Et unusquisque eorum omnia maneria sua dominica in comitatu et hundredo per unum senescallum presentatum defendere possit.

8. Concedo etiam quod, mortuo viro, uxor sua per quadraginta dies pacem habeat in domo sua. Et heres suus, si etatem habuerit, per rationabile relevium hereditatem suam habeat, scilicet feodum militis per centum solidos. Neque domina neque heres maritetur ubi disparigetur, set per gratum et assensum generis sui maritetur. Et eorum legata teneantur.

9. Et nullus eorum nativum suum amittat occasione, si in civitate Cestrie venerit, nisi ibi manserit per unum annum et unum diem sine calumpnia.

10. Et propter grave servicium quod in Cestresiria faciunt, nullus eorum extra Limam servicium mihi faciet, nisi per gratum suum et ad custum meum. Et si milites mei de Anglia summoniti fuerint, qui mihi wardam apud Cestriam debent, et venti sint ad wardam suam faciendam, et exercitus aliunde inimicorum meorum non sit in presenti, nec opus fuerit, bene licet baronibus meis interim ad domos suas redire et requiescere. Et si exercitus inimicorum meorum promptus fuerit de veniendo in terram meam in Cestresiria, vel si castellum assessum fuerit, predicti barones cum exercitu suo et nisu suo statim ad summonitionem meam venient ad removendum exercitum illum ad posse suum. Et cum exercitus ille de terra mea recessus fuerit, predicti barones cum exercitu suo ad terras suas redire poterunt et requiescere, dum milites de Anglia wardam suam faciunt et opus de eis non fuerit, salvis mihi serviciis suis, que facere debent.

11. Concedo etiam eis quod in tempore pacis tantum duodecim servientes itinerantes habeantur in terra mea cum uno equo, qui sit magistri servientis, qui etiam prebendam non habeat a Pascha usque ad festum sancti Michaelis, nisi per gratiam, et ut ipsi servientes comedant cibum qualem in domibus hominum invenerint, sine emptione alterius cibi ad opus eorum, nec in aliquibus dominicis baronum comedant. Et in tempore guerre per consilium meum aut iusticiarii mei et ipsorum, ponantur servientes sufficientes ad terram meam custodiendam, prout opus fuerit.

12. Et sciendum est quod predicti barones peticiones subscriptas, quas a me requirebant, omnino mihi et heredibus meis de se et heredibus suis remiserunt, ita quod nihil in eis de cetero clamare poterunt, nisi per gratiam et misericordiam meam; scilicet, senescallus peticionem de wrec et de pisce in terram suam per mare deiecto, et de bersare in foresta mea ad tres arcus, et de percursu canum suorum; et alii peticionem de agistiamento porcorum in foresta mea et de bersare ad tres arcus in foresta mea, vel ad cursus leporariorum suorum in foresta in eundo versus Cestriam per summonitionem vel in redeundo; et petitionem de misericordia iudicum de Wich triginta bullonum salis, set erunt misericordia et leges in Wich tales quales prius fuerunt.

13. Concedo igitur et presenti carta mea confirmo de me et heredibus meis communibus militibus omnibus et libere tenentibus totius Cestresirie et eorum heredibus omnes predictas libertates habendas et tenendas de baronibus meis et de ceteris dominis suis, quicumque sint, sicut ipsi barones et milites et ceteri libere tenentes eas de me tenent.

Hiis testibus Hugone abbate sancte Werburge Cestrie, Philippo de Orrebi tunc tempore iusticiario Cestrie, Henrico de Aldithelega, Waltero Deyville, Hugone dispensario, Thoma dispensario, Willelmo pincerna, Waltero de Coventria, Ricardo Phitun, Roberto de Coudrey, Ivone de Kaletoft, Roberto de Say, Normanno de Paunton, Roberto dispensario, Roberto Deyville, Matheo de Vernun, Hamone de Venables, Roberto de Masci, Alano de Waley, Hugone de Culumbe, Roberto de Pulfort, Petro clerico, Hugone de Pasci, Joceralmo de Helesby, Ricardo de Bresci, Ricardo de Kingesle, Philippo de Therven, Lithulfo de Thwamlawe, Ricardo de Perpunt, et toto comitatu Cestrie.

The following translation is by Jonathan Pepler and is reproduced with his permission.

Ranulf Earl of Chester, to the constable, steward, justiciar, sheriff, barons and bailiffs and all his men and friends, both present and future, who will see or hear this present charter, greeting. Know that I, being signed with the cross, have, for the love of God and at the petition of my barons of Cheshire, granted to them and their heirs, from me and my heirs, all the liberties written hereunder in this present charter, to be held and had in perpetuity, namely:

1. That each one of them may have his own court free from all pleas and complaints being moved in my court, except pleas pertaining to my sword, and that if any one of his men shall be taken for any offence, throughout his lordship, he may be reclaimed without ransom, so that his lord may bring him to three county [courts], and may take him back acquitted, unless a sacraber pursues him.

2. And if a stranger, who is trustworthy, should come into their lands and wishes to stay there, it may be lawful for the baron to have and keep him, saving to me those avowers who may come to me of their own accord and others who on account of transgressions committed elsewhere may come to my dignity, and not to them.

3. And each one of the barons, when need may require in war, shall fully perform the service of as many knights’ fees as he holds, and their knights and free tenants shall have breastplates and haubergeons, and may defend their fees with their own bodies, even if they are not knights. And if there be any one of them such that he cannot defend his land with his own body, he may put another sufficient person in his place. Nor shall I make their villeins swear to arms, but I grant to them quit their villeins who came to my avowry through Ranulf de Davenham, and their other villeins whom they may reasonably show to be theirs.

4. And if my sheriff or any serjeant in my court shall have accused any one of their men, he may defend himself by 'thwertnic' on account of the 'sirevestoth' which they pay, unless the suit pursues him.

5. And I grant them quittance of sheaves and offerings which my serjeants and beadles were accustomed to demand. And that if any judge or suitor of the hundred or county should incur amercement in my court, a judge may be quit of the amercement for two shillings and a suitor for twelve pence.

6. And I grant them liberty of assarting their lands within the bounds of their husbandry in the forest, and if there should be land or territory within the bounds of their vills, which was formerly cultivated, and wood does not grow there, they may cultivate it without harbourage, and they may take ‘husbote’ and ‘haybote’ in their wood of all sorts of timber without view of the forester, and they may give or sell dead wood to whomever they wish. And their men may not be impleaded concerning the forest for the above mentioned, unless they are caught red-handed.

7. And each one of them may defend all his demesne manors in the county [court] and hundred [court] by one steward there present.

8. And I grant that, when a man dies, his wife may peacefully occupy his house for forty days. And his heir, if he is of age, may have his inheritance for a reasonable relief, namely a hundred shillings for a knight's fee. Neither the lady nor the heir shall be married where this would involve loss of rank, but by the favour and assent of their family. And their legacies shall be secured.

9. And none of them may lose his villein in the event of him coming into the city of Chester, unless he stays there for a year and a day without challenge.

10. And on account of the heavy service which they perform in Cheshire, none of them shall do service for me beyond the Lyme, unless of their own free will and at my expense. And if my knights from England who owe me ward at Chester are summoned, and have come to perform their ward, and the army of my enemies from elsewhere is not present, and there is no necessity, my barons may meanwhile freely return to their homes and rest. And if an army of my enemies should be prepared to come into my land in Cheshire, or if the castle should be besieged, the aforesaid barons will come immediately at my summons with their army and exertions, to remove that army as far as they are able. And when that army shall have retreated from my land, the said barons can return to their lands with their army, and rest, while the knights from England perform their ward and there shall be no necessity for them, save for the services which they must do for me.

11. And I grant to them that in time of peace only twelve itinerant serjeants may be kept in my land with one horse which is for the master serjeant, and which may not have provender from Easter until the feast of Saint Michael, except voluntarily; and that those same serjeants may eat such food as they may find in men's houses, without the purchase of other food for their use, nor may they eat in any of the barons' demesnes. And in time of war, on my advice or that of my justiciar and themselves [the barons], sufficient serjeants may be put in place to guard my land as the need may be.

12. And may it be known that the aforesaid barons have completely remitted to me and my heirs, on behalf of themselves and their heirs, the following petitions which they were asking from me, so that they can claim nothing in relation to them henceforth, unless by my grace and mercy: namely, the steward his petition for wreck and fish washed up on his land by the sea, and for shooting in my forest with three bows, and for hunting with his dogs; and others the petition for the agistment of pigs in my forest and for shooting with three bows in my forest, or for the coursing of their hares in the forest on the way to, or returning from Chester in response to a summons; and the petition for the amercement of the judges of Wich thirty boilings of salt, but the amercement and laws in Wich shall be as they were before.

13. I grant therefore, and by this my present charter confirm, for me and my heirs, to all common knights and free tenants of the whole of Cheshire and their heirs, all the aforesaid liberties, to be had and held of my barons and of their other lords, whoever they may be, just as the barons and knights themselves and other free tenants hold them of me.

These being witnesses: Hugh Abbot of Saint Werburgh Chester, Philip de Orreby at that time justiciar of Chester, Henry de Aldithlega [Audley], Walter Deyville, Hugh the dispenser, Thomas the dispenser, William the butler, Walter de Coventry, Richard Phitun, Robert de Coudrey, Ivo de Kaletoft, Robert de Say, Norman de Paunton, Robert the dispenser, Robert Deyville, Matthew de Vernun [Vernon], Hamo de Venables, Robert de Masci, Alan de Waley, Hugh de Culumbe, Robert de Pulfort [Pulford], Peter the clerk, Hugh de Pasci, Joceram de Helesby [Helsby], Richard de Bresci, Richard de Kingesle [Kingsley], Philip de Therven, Lithulf de Thwamlawe [Twemlow], Richard de Perpunt and the whole county [court] of Chester.

Several of the clauses13 address issues familiar from Runnymede, but not in the same way. Nos. 1 and 4, for example, echo the concern of Magna Carta clause 34 that ‘a free man might lose his court’, since they deal with the rival claims of the earl’s (in a Cheshire context, the county) court and the barons’ courts to jurisdiction over those who dwelt on baronial estates. In no. 1, the earl acknowledges the barons’ entitlements but reserves the most serious offences, the ‘pleas of my sword’, to his own court, while in no. 4, accepting that the barons pay a due called ‘sirevestoth’ for the privilege, he affirms the right of those accused in his court to use the defence of ‘thwertnic’ (a blanket denial or ‘thorough no’) which carried with it release to the jurisdiction of one’s baronial lord. The concluding phrases of both these clauses, with their references to a ‘sacraber’ (or sacrabar, a private prosecutor) and a ‘suit’ (of witnesses) respectively, take us back to Magna Carta clause 38, with its prohibition of unsupported allegations by local officials.14

Among other clauses, no. 5 limits penalties imposed by the earl’s court, but almost certainly for the specific offence of non-attendance by judges and suitors, a far more restricted context than that envisaged in Magna Carta clauses 20 and 21. No. 6 grants various rights within the Cheshire forests, to assart, cultivate land and sell dead wood, but without the calls for disafforestation and the curbing of officials which characterised the ‘forest’ clauses of Magna Carta (44, 47 and 48). No. 8 duly protects widows and heirs but makes no specific mention of wardship, and the subject is tackled with a brevity which suggests that the outrage which lay behind Magna Carta clauses 2 - 8 had no parallel in Cheshire. By contrast, no. 10, which deals with limits to military service and the performance of castle guard, as in Magna Carta clauses 16 and 29, goes into a level of detail befitting a frontier county accustomed to threatened or actual attack from the Welsh. Significant points here include the treatment of the Lyme as a border beyond which Cheshire knights are not obliged to fight and the expectation that the garrisoning of Chester castle should fall primarily upon fees of the honour outside the county. No. 11, which places limits on the provisions which can be claimed by officials, bears some resemblance to Magna Carta clause 28, although the Cheshire charter focuses specifically upon the entitlements of the itinerant law-enforcement officers known as serjeants. The final clause, no. 13, provides the most important link to Magna Carta of all, with its insistence that ‘all common knights and free tenants of the whole of Cheshire’ should enjoy the same liberties in holding from the barons, as the barons would have in their holdings from the earl. The parallel here with clause 60 of Magna Carta, with its extension of the concessions to ‘all men of our realm’, is the strongest evidence we have that those who framed the Cheshire document were consciously seeking to replicate the king’s charter, suitably adapted to local circumstances.

There are other clauses, however, which bear no resemblance to the grants made at Runnymede. Nos. 2 and 3 refer to Cheshire’s ‘avowry’ system, whereby fugitive villeins from outside the county, including those fleeing justice, could find refuge on the estates of the earl or his barons, normally with an obligation that (alongside agricultural labour) the menfolk among them would provide a fighting force for their lord. The clauses suggest that the earl had been claiming too many of these ‘avowers’ for himself, apparently through the efforts of Ranulf de Davenham, presumably some sort of agent.15 No. 7 seems to be an innocuous confirmation for Cheshire of what was already established practice elsewhere. No. 9 raises an issue familiar from borough customs across the kingdom, whereby urban residence for a year and day would secure freedom from villeinage.16 This had not bothered the negotiators at Runnymede, probably because, in an age of burgeoning population, the loss of villeins to the towns could be borne with equanimity, and in places was welcomed. But migration from the countryside into Chester - prospering as a port in the wake of Henry II’s acquisitions in Ireland - was evidently of real concern to the Cheshire barons, who wanted their entitlements to reclaim their villeins spelled out.

Clause 12 of the Cheshire charter, another which has no counterpart in Magna Carta itself, is perhaps the most remarkable. It is clear that the baronial negotiators at Runnymede did not secure everything they wanted - a ban on service overseas being a good case in point - but King John’s charter did not advertise the fact. Earl Ranulf, however, seems to have been quite happy to itemise the petitions he had turned down, most of which seem to have related to the aspirations of particular individuals or interest-groups rather than the baronial community as a whole. His hereditary steward was Roger de Montalt, who as ‘baron of Mold’ held land on the south-west side of the Dee estuary; he would have been well placed to profit from mishaps to shipping using the port of Chester, had the earl been prepared to allow this. Other rejected petitions related to privileged use of the earl’s forests, especially for the stylised bloodsports associated with parks within the forests: shooting a fixed number of arrows at deer driven into the target area and watching hares being chased by dogs along a prepared course. The clause even suggests that the petitioners were hoping that sport would be laid on whenever they were summoned to Chester! Finally, the request concerning amercements in ‘Wich’ leads us to the special courts for the salt-making towns of mid-Cheshire, the peculiarities of which are described in Domesday Book. Whatever the precise request was - and it may have been only for more flexibility over the penalties which could be imposed - the earl preferred to leave well alone.

It is tempting to suggest that Earl Ranulf welcomed the opportunity to issue the ‘Magna Carta of Cheshire’, as a demonstration of his standing in the county in place of the king. That would be wrong. If we are correct in dating the document to the late summer of 1215, it would have been issued at a time when the king’s friends and enemies alike saw Magna Carta as a humiliating constraint on royal authority, one which John was actively seeking to annul. There was nothing here with which the earl of Chester would have wished to associate his own government of Cheshire. Even on the three occasions during his lifetime when Magna Carta was reissued, in 1216, 1217 and 1225 - always with the intention of affirming rather than undermining the authority of the king - he chose not to renew his charter for Cheshire. Yet if Ranulf granted concessions to his Cheshire barons reluctantly, there was nevertheless some political capital to be gained from the exercise. The experience of the earl presiding over the county court, in order to make grants some of which were clearly modelled on those in Magna Carta, was striking testimony to a self-conscious sense of Cheshire’s independence from the rest of the kingdom. Moreover, the charter was carefully presented so as to minimise the impression that Ranulf’s power over the county was in any way diminished. Several of the clauses - nos. 1, 2, 3, 10 and 11 - specifically affirmed the earl’s entitlements as well as those of his barons. He openly asserted his right to reject some of the petitions. And the 29 witnesses largely comprised the earl’s trusted advisors and officers, along with a selection of those doing suit to the county court, with preference apparently given to those like Joceram of Helsby and Richard of Kingsley with a proven record of past service to Ranulf, as sheriff or forester.17 The message coming through loud and clear was that, notwithstanding his concessions, the earl remained in control.

What can we reasonably infer from the various clauses about Ranulf III’s regime in Cheshire? Given the circumstances in which the Runnymede Magna Carta was produced, the fact that there is a clause dealing with a particular issue repeatedly leads to the conclusion that the king must have been abusing his powers in this area. With the Cheshire Magna Carta, we cannot make an equivalent assumption. Occasionally, there is a pointed reference to a named individual (clause 3) or we are specifically told that there would be a change of practice (clause 5); in these cases, particular grievances must lie behind the statements. Wherever the earl’s officials are mentioned (as in clause 11), we may suspect that they had been over-reaching themselves and were being reined in. But much of the charter, especially where it is concerned with the maintenance of distinctive Cheshire customs, may have been rooted in the barons’ wish to secure a guarantee of their privileges by having them written down. We should not assume without further evidence that the earl had been causing serious offence. The barons’ chief anxieties stemmed partly from Cheshire’s position as an under-populated, under-resourced county on a vulnerable frontier, and partly - against this background of limited resources - from what they perceived as the unreasonable activities of the earl’s officers, who levied unfair exactions and took their men into custody: all this in a county where shortage of manpower prevented the full exploitation of arable land, curtailing income from estates, and where the demands of military service were liable to reduce that manpower even further. These were the main sources of friction between the earl and his Cheshire barons and - if we leave to one side clause 8 and the one immediately preceding it about stewards serving as representatives in court - all the clauses offering substantive concessions, from 1 to 11, can at least partly be read in this light.

So we encounter the barons’ concerns to ensure that, as far as possible, the residents of their estates should remain within the jurisdiction of their own courts, rather than the earl’s, so that they could retain some control over their fate (clauses 1, 4, 6); to assert their own rights - alongside those of the earl - to settle ‘avowers’ on their estates, as workforce and potential soldiers, and to reclaim villeins living in Chester (clauses 2, 3, 9); to remove restrictions on extending the cultivated area within the earl’s forests (clause 6); to define the limits of their military obligations to the earl (clauses 3, 10); and to curb the impositions of the earl’s officials (clauses 5, 6, 11). The promises which emerged from all this, laced with particulars such as ‘thwertnic’ and the significance of the Lyme, reinforced the distinctive county identity out of which the demands had arisen, deepening the sense of Cheshire’s ‘special status’ so that it outlasted the takeover by the crown in 1237. Some of the concessions were probably no more than confirmations of existing practice, others were certainly new. Among them were several which represented extensions to the baronial community at large of what had already been specially granted to a favoured few. For example, the earl’s sometime chancellor, Peter the clerk, had at different times specifically been given ‘his own court free from all pleas and causes, except for pleas pertaining to my sword’, freedom from the obligation to do suit to county and hundred courts, and release from the requirement to feed the earl’s itinerant serjeants (compare clauses 1, 5 and 11).18 There was a parallel here with King John’s Magna Carta, since a culture of selling privileges had developed following the accession of Richard I and the baronage of England had come to think, as Holt put it, ‘that what some could buy should be equally available to all’.19 Collectively, the various clauses in the Magna Carta of Cheshire, like its great Runnymede exemplar, offer an insight into the hopes and fears of the early-thirteenth-century landholding class - but here in a context away from the main centres of power and mostly below the ranks of the major tenants-in-chief.

1 | On the circumstances, see J.R. Studd, ‘The Lord Edward’s Lordship of Chester, 1254-72’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol. 128 (1979), pp. 1-25, at pp. 15-16. |

2 | E.g. B.E. Harris, ‘Ranulph III Earl of Chester’, Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, vol. 58 (1975), pp. 99-114, at p. 112; Charters of the Anglo-Norman Earls of Cheshire, c.1071-1237, ed. G. Barraclough (Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol. 126, 1988: hereafter CEC), p. 388; Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004), vol. 46, p. 57; cf. D. Carpenter, Magna Carta (London, 2015), pp. 147, 152, 306. An inquest into military service due from Cheshire in 1288 declared that it was to be done ‘secundum proporttum magne communis carte Cestrisire’, i.e. ‘according to the tenor of the great common charter of Cheshire’ (Calendar of County Court, City Court and Eyre Rolls of Chester, 1259-1297, ed. R. Stewart-Brown, Chetham Society, new series, vol. 84, 1925, pp. 109, 113). |

3 | Annales Cestrienses, ed. R.C. Christie (Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol. 14, 1887), pp. 50-51. |

4 | Calendar of Close Rolls, 1247-51 (London, 1922), pp. 185-86. |

5 | CEC, pp. 388-91; the text of 1300 was used as the basis for the edition of the charter which appears (with clauses numbered differently) in Chartulary or Register of St Werburgh, Chester, ed. J. Tait, vol. 1 (Chetham Society, new series, vol. 79, 1920), pp. 101-107. |

6 | 1158-62 and 1181-87: Cheshire in the Pipe Rolls, ed. R. Stewart-Brown (Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol. 92, 1938), pp. 1-25. |

7 | Liber Luciani de Laude Cestrie, ed. M.V. Taylor (Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol. 64, 1912), p. 65. A helpful map indicative of the extent of the Lyme appears in N.J. Higham, The Origins of Cheshire (Manchester, 1993), p. 120. |

8 | CEC, nos. 282, 374; D. Crouch, ‘The Administration of the Norman Earldom’ in A. T. Thacker, ed., The Earldom of Chester and its Charters (Chester, 1991), pp. 69-95, at pp. 72-73. |

9 | The most convenient summary of Earl Ranulf III’s career is that by Richard Eales in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004), vol. 46, pp. 56-59. There are also two full-length biographies, both with subtitles which hint at interpretations which court controversy: J.W. Alexander, Ranulf of Chester: a Relic of the Conquest (Athens, Georgia, 1983) and I. Soden, Ranulf de Blondeville: the First English Hero (Stroud, 2009). |

10 | Conventionally there were eight large estates regarded as ‘baronies’ in Cheshire, although a few other major landholders may have been involved in negotiations: Calendar of County Court, City Court and Eyre Rolls of Chester, 1259-1297, ed. R. Stewart-Brown (Chetham Society, new series, vol. 84, 1925), pp. xlvi-xlvii; Victoria County History: Cheshire, vol. 1 (1987), pp. 306-14. |

11 | J.C. Holt, Magna Carta (2nd edn., Cambridge, 1992), pp. 494-95; cf. Carpenter, Magna Carta, pp. 375-79. |

12 | See e.g. J.C. Holt, The Northerners (2nd edn., Oxford, 1992), pp. 1, 26. |

13 | There is a detailed commentary on the various clauses, and on the charter generally, in a recent publication available from Cheshire Local History Association via Cheshire Archives and Local Studies: G.J. White, The Magna Carta of Cheshire (with a translation of the Charter by J. Pepler). |

14 | On ‘thwertnic’ and ‘sacrabar’, cf. J.M. Kaye, ‘The Sacrabar’, English Historical Review, vol. 83 (1968), pp. 744-58. |

15 | R. Stewart-Brown, ‘The Avowries of Cheshire’, English Historical Review, vol. 29 (1914), pp. 41-55; G. Barraclough, ‘Some Charters of the Earls of Chester’ in P.M. Barnes and C.F. Slade, ed., A Medieval Miscellany for Doris Mary Stenton (Pipe Roll Society, new series, vol. 36, 1962 for 1960), pp. 25-43, at pp. 35-37. |

16 | A. Ballard, British Borough Charters, 1042-1216 (Cambridge, 1913), pp. 103-105. |

17 | CEC, p. 169; G. Ormerod, History of the County Palatine and City of Chester (rev. edn. by T. Helsby, London, 1882), vol. 2, pp. 62, 72, 87, 90. |

18 | CEC, pp. 281-82, 285. |

19 | Holt, Magna Carta, p. 51. |

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265