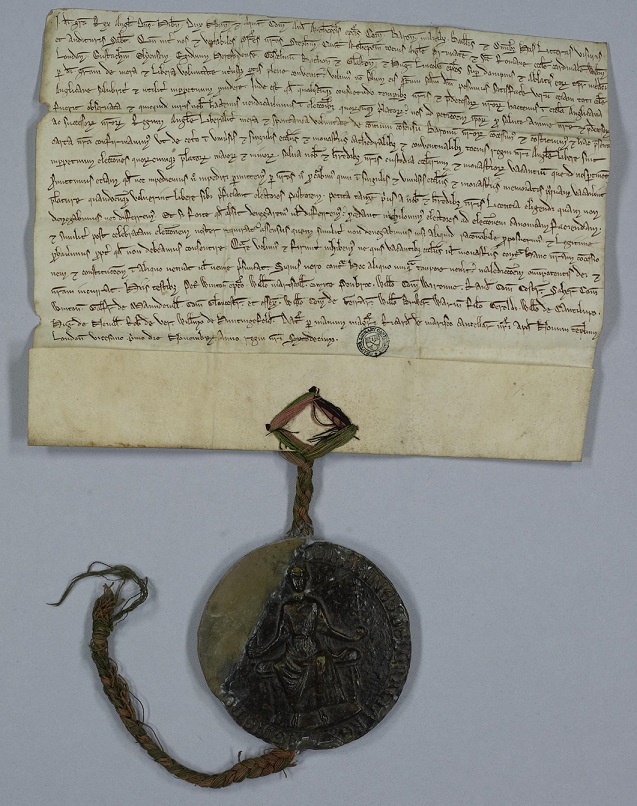

The Freedom of Election Charter

August 2014,

On 21 November 1214, seven months before Magna Carta was sealed at Runnymede, King John issued another charter of liberties. This charter, which promised freedom of election to the English Church, is less well known than its much-revered counterpart, but its modern-day obscurity should not be taken as an indication of its insignificance. In the early thirteenth century, the appointment of a new bishop was an act with real consequences for both church and state, and the manner in which such men were appointed had been the subject of fierce debate for many years.1

Indeed, John’s decision to grant the Freedom of Election charter can only be properly understood in the context of England’s post-conquest electoral history. Between 1066 and the early thirteenth century, English episcopal elections were dominated by the crown. Although it was acknowledged that bishops should be canonically elected, the idea was relatively ill-defined, and it was widely accepted that secular rulers would be heavily involved. Norman and Angevin kings took their powers over such appointments for granted; their voice in such matters was decisive, and they were rarely disappointed in their attempts to create a loyal episcopate made up primarily of king’s men.

The clearest indication of the extent of royal influence over episcopal appointments in the long twelfth century is to be found in the Constitutions of Clarendon (1164), which state that:

And when they come to provide for the church, the lord king must cite the chief persons of the church, and the election must take place in the chapel of the lord king himself, with the assent of the lord king, and the advice of the persons of the realm whom he shall have summoned to do this. And the person elected shall there do homage and fealty to the lord the king as to his liege lord for his life and limbs and earthly honour, saving his order, before he can be consecrated.2

Although this clause stopped short of asserting a direct right of appointment, and is broadly compatible with canon law, royal authority is unquestionably predominant throughout the electoral process as here described.3 The reality of the situation is nicely encapsulated in the writ Henry II allegedly sent to the monks of Winchester in 1173: ‘I order you to hold a free election, but nevertheless I do not wish you to accept anyone except Richard, my clerk, the archdeacon of Poitiers.’4

Nevertheless, the tide was beginning to turn, and over the next five decades electoral freedom became an increasingly significant issue in church–state relations. In 1168, Pope Alexander ordered Henry II to allow free elections to be held and to desist from making his own nominations.5 Four years later, the cardinal legates Albert and Theodwin secured an informal agreement from Henry II that he would permit free elections to take place,6 although this was soon broken by the king.7 St Hugh of Lincoln also had something to say on the matter, accusing Henry of ‘abusing the powers which his predecessors had usurped in connection with the appointments of bishops and abbots’, and arguing that he should ‘permit freedom of election in accordance with the rules of canon law’.8 The king was not the only target for such criticism: Pope Alexander III rebuked Archbishop Richard of Dover for confirming elections made in the king’s chamber.9

Growing ecclesiastical censure meant that the formal processes of election were usually observed, but both Henry II and Richard I managed to maintain strong personal control of English elections.10 At the time of John’s accession, therefore, the idea of the king offering pledges of electoral freedom would have been almost unthinkable, but the events of the next fifteen years changed that. During the early years of John’s reign the crown still controlled elections, but was increasingly subject to papal displeasure for doing so.11 In February 1203, Innocent III complained to John that ‘You are claiming for yourself power beyond your rights, you are applying the revenues of the churches to your own uses, you are attempting to prevent elections, and in the end by your unlawful persecution you are forcing the rightful electors to choose in accordance with your arbitrary decision.’ Innocent was particularly disturbed by John’s approach to the see of Lincoln, which had been vacant for over two years, and accused him of delaying the election for his own financial gain.12

When Hubert Walter, archbishop of Canterbury, died in July 1205, the simmering tensions between crown and papacy finally boiled over. An election was held at Canterbury, but produced a split result: some of the monks elected their sub-prior but others favoured the royal candidate, John de Gray, bishop of Norwich. Both parties sent delegations to Rome to seek confirmation of their choice, but Innocent rejected both candidates. A new election was held at the papal curia, resulting in the appointment of Cardinal Stephen Langton- a choice warmly endorsed by the pope.13

John, on the other hand, was less than impressed by the new archbishop. He refused to recognise the new archbishop, claiming that royal assent to the holding of an election had not been sought and that Langton was unknown to him. Faced with Innocent’s threats that he should ‘humbly agree with us’ or face ‘a difficulty from which he could not easily be freed’14, John remained bullish. He could not prevent the consecration of Archbishop Stephen, which took place in Italy in June 1207, but did prevent him from entering England, declaring Langton’s supporters to be public enemies and seizing the estates of the see.15 Deadlock had now been reached, and in March 1208 England was placed under interdict.16 If John was meant to be cowed by this measure, then it failed spectacularly, since he merely exploited the new financial opportunities it offered to him.17 He also continued to add ‘transgression to transgression’, by delaying and hindering free elections.18 In November 1209 he was excommunicated.

Only in July 1214, after England had become a papal fief, was the interdict formally lifted.19 The conduct of episcopal elections nevertheless continued to be a troublesome issue, largely due to the role played by Nicholas, cardinal-bishop of Tusculum, the papal legate in England during the period 1213-14. The legatine mission was aimed at reconciling John to the Roman Church, and royal control of elections was not seriously threatened by the legate’s presence. Nicholas’ policy was based on papal orders, which not only required him to respect the king’s right both to grant licence to elect and to give assent to the outcome, but also allowed him to pay considerable respect to the royal wishes. Suitable men were to be elected or postulated according to Nicholas’ recommendation, and a suitable man was defined as one who was ‘not only distinguished in life and learning, but also loyal to the king, profitable to the kingdom, and capable of giving counsel and help’.20 It was even suggested that ‘any honourable request of his which preserves the liberty of the church’ should be granted21 – a suggestion that says a lot about Innocent III’s desire to resolve the dispute with John, as well as undermining the traditional view that Innocent was aiming at world domination. Cathedral chapters were obliged to accept such legatine recommendations,22 and Nicholas’ respect for the king’s wishes soon prompted complaints to the papal curia. It was alleged that the legate was making too many concessions to the crown, even allowing royal proctors to attend elections, to the detriment of ecclesiastical liberties.23

Unsurprisingly, John was happy to comply with this form of bishop-making,24 but Archbishop Stephen was rather less pleased, complaining that Nicholas was appointing unworthy men, recommended by the king, to vacant churches.25 By January 1214, some form of agreement over the conduct of elections had been reached, probably with papal involvement; we know this because John wrote to Langton that ‘the form notified to us for the making of elections is acceptable to us saving in all things our right’. But even as John asserted that ‘there is no controversy between us’,26 the archbishop was canvassing the support of the other bishops, and sending proctors to both the legate and the pope to reassert his archiepiscopal rights.27 Legate Nicholas remained in England until November 1214, when he was recalled to Rome.28 But the conduct of episcopal elections remained the subject of considerable dispute between the king and the church. It was at this point, on 21 November, that John granted the Freedom of Election charter.

It is clear, then, that the Freedom of Election charter was the product of a point in time when the ever-present gulf between royal and ecclesiastical approaches to the filling of episcopal vacancies had become untenably wide. What exactly did John concede in November 1214? Superficially, the answer is straightforward: he pledged that, henceforth, ‘the elections of all prelates whatsoever … be free forever’. The simple fact that John had acknowledged this right was a major triumph for both the English Church and the papacy. Whereas the Constitutions of Clarendon provided a vigorous statement of the crown’s rights over the electoral process, John’s charter renounced ‘the custom in our times and of our predecessors’ and emphasizes the limits of royal power. The chapter had to seek licence to elect from the crown, but the king would not ‘deny or defer’ its issue; if he did so, the election might go ahead regardless, and thus it was no longer possible for the crown to prevent elections by withholding the licence. This licence having been granted, the king ‘will neither hinder not suffer nor procure to be hindered by our ministers that … the electors should, whenever they will, freely set a pastor over them’. Although the chapter must seek royal assent to the outcome of their election, this could only be refused if the king can ‘put forth some reasonable excuse and lawfully prove it’. Edward II would later recall, somewhat wistfully, that ‘before the time of King John, all his ancestors, kings of England … freely conferred bishoprics without any contradiction’;29 henceforth, because of this charter, it would never again be so. Through the concessions made in 1214, John ceded the direct personal control over ecclesiastical elections his predecessors had enjoyed.

And yet, these concessions were perhaps not as extensive as they initially appear when one reads the charter for the first time. In a typically controversial passage, Richardson and Sayles argued that the charter was essentially worthless to the church, being little more than ‘an empty concession’.30 This is clearly an overstatement, yet there is some truth in their assertion, for John retained considerable powers over the electoral process – both official and unofficial. The right to grant the congé d’élire was, in many ways, a symbolic one, since it could no longer be denied – but the symbolism of the king allowing the chapter to hold an election was nevertheless important. It would henceforth be impossible for a king to prolong vacancies deliberately for financial gain by refusing licence – a practice for which the Angevins had become notorious. However, the reassertion of the custom of regalian right31 – the holding of the episcopal temporalities by the crown during a vacancy – was not without value, partly because even a relatively brief vacancy could bring the king substantial amounts of extra revenue, but also because the threat of damage to these properties could prove a powerful incentive to elect the king’s candidate. Similarly, the statement that royal assent could only be withheld if ‘reasonable excuse’ could be found was open to considerable exploitation. The complexities of canon law were such that it was almost always possible to find a flaw in the conduct of an election or the quality of an elect if one were inclined to do so.

If what the charter said is significant, what it did not say may be even more important. Although it was no longer possible for the king to impose his wishes on the chapter, he could still indicate his wishes to the electors. In fact, there was no formal rejection of the traditional practice of holding elections in the royal presence – although this was clearly at odds with the spirit of the charter, and does seem to have stopped – or of the practice that replaced it, the sending of royal proctors to the electors. Based on the contents of this document, there was no reason why elections should not continue to take place as they had throughout Nicholas’ time as legate, not directly under royal control but still heavily influenced by royal wishes.

If the charter did little to change the status quo, then why was it issued? Answers to this question have traditionally focused on the political difficulties John faced during the last years of his reign. His position, it is argued, had already been weakened by the protracted dispute with the church, and by the manner in which this dispute was ended. When John returned to England from the continent in October 1214, his kingship had been further undermined by defeat at Bouvines. Domestic opposition to his rule was rapidly growing.32 In a desperate attempt to contain dissent, John granted the Freedom of Election charter, hoping to detach the English Church from the rebellious barons.33

This interpretation makes a great deal of sense, since John certainly faced significant political difficulties in late 1214. The bishops, and in particular Archbishop Stephen, were known to be dissatisfied with various aspects of his rule, including his perceived lack of respect for electoral liberties.34 John was clearly engaged in settling his differences with the church at this time (he made a series of grants made to senior churchmen on or around 21 November35) and granting a charter that pledged electoral freedom was certain to please the clergy, serving as a form of compensation for the difficulties of the past decade.36 It is therefore hard to escape the conclusion that the Freedom of Election charter was granted as part of a campaign to conciliate the episcopate.

Nevertheless, to explain the charter solely in such terms is overly simplistic. To do so is to imply that John came to an agreement with the English Church only when he was backed into a corner; that it was a document granted with the sole aim of pleasing the church; that John had nothing to gain from such an agreement. The reality is rather more complex, for electoral disputes were not just an English problem. Whilst Stephen Langton was undoubtedly much concerned by the question of electoral freedom, his interest was matched by that of Innocent III, whose pontificate was characterized by his insistence on the importance of ecclesiastical liberties. Significantly, John was not the only European ruler to grant electoral freedom to the local church during Innocent’s pontificate; similar concessions were made in Sicily, the Romano-German Empire, Austria and Aragon. These continental parallels reaffirm the notion that such grants were seen as a source of political capital for embattled rulers, but they also show that debates about electoral procedure were not limited to England, and suggest that this charter was more than a result of the tensions between John and Langton. Instead, it was about the nature of the relationship between regnum and sacerdotium as it was being defined and developed in the early thirteenth century.

A common theme in all of these agreements was papal involvement; such promises pleased not only the English Church, but also the pope. This charter was issued in the wake of England’s conversion into a papal fief, and John is known to have skilfully exploited his position as a papal vassal; Cheney described his decision to take the cross in March 1215 as ‘a shrewd move’.37 The charter might be described in similar terms, for it was sure to enhance John’s standing in papal eyes. There is certainly strong evidence of papal influence over the contents of the charter. In particular, a comparison of its contents with a letter sent by Innocent III to Legate Nicholas in late 1213 or very early 1214 is extremely suggestive. Both texts require the electors to seek licence to elect from the crown; both anticipate the holding of the election away from court; both emphasise the need for royal assent, which will not be delayed. It seems impossible that those involved in drafting the charter did not have this papal letter in mind. Amongst their number must surely have been its recipient, the Legate Nicholas who, like John, would have been aware of the impact this grant would have in Rome. It is even possible (although entirely unprovable) that Nicholas had been tasked with securing such an agreement during his mission to England.

To date, historians have almost unanimously assumed that, whilst the charter was pleasing to both the English Church and to Rome, it was utterly distasteful to John. Undoubtedly he would have preferred to enjoy the same control over elections that his predecessors had exercised. And yet, he must also have been able to see the charter’s potential value, for it brought long-term benefits to the crown, as well as serving as a ploy to stave off trouble in the short term. In a climate in which royal control of elections appeared to be under threat – and this was certainly the case during John’s reign – having one’s rights outlined in a charter confirmed by the pope was no bad thing. The need to secure such a charter became all the more pressing in November 1214, when Legate Nicholas was suddenly recalled to Rome.38 From John’s perspective, this changed everything. With the legate gone, Archbishop Stephen once again became the most powerful churchman in England- and his stance on elections was well known. It was surely not a coincidence that John decided to issue this charter only weeks before his ally left England.

The Freedom of Election charter was the product of a short-term crisis, but it had a long afterlife. It was almost immediately reissued, on 15 January 1215, shortly after the Epiphany great council. The reasons for this reissue are obscure, since the text and witness list of the two versions are identical, but perhaps relate to the dispatch of the charter to Rome. The party responsible sending the document to the papal curia is also unknown. Cheney argued that it must have been carried by archiepiscopal proctors; he could not credit the possibility that John was responsible, and even thought that the king may have appealed against the charter.39 But the possibility that John sent the charter to Rome, or that he cooperated with its sending, cannot be discounted. At some point in March 1215, an English delegation, which had been preparing for departure since mid-November, arrived in Rome. The party carried with them letters of credence to the pope and cardinals, given to them by John.40 Were they also carrying the charter? The timescale fits: the charter received papal confirmation on 30 March.41 Matthew Paris certainly thought that John had a hand in its dispatch to the papal curia, stating both that the king entreated the pope to confirm it and that the confirmation was sought by the king, magnates and prelates.42 In the opening clause of Magna Carta, John himself claimed that ‘we … obtained confirmation of this from the Lord Pope Innocent III’.43

Whoever sent the charter to Rome, it arrived before the end of March 1215, when it was confirmed by a papal letter of grace.44 Its value was greatly strengthened by this papal confirmation, and was further reinforced in June, when it was summarized in the first clause of Magna Carta.45 Its inclusion is usually attributed to Langton, and there is no reason to doubt this – although, again, it may not have been as repugnant to John as has often been supposed. Its association with Magna Carta was, however, to be short-lived, for this section of the clause was removed from all subsequent issues. Its deletion in 1216 should be understood as a response to political circumstances, since at this time it might confer not freedom from royal intervention, but freedom to elect supporters of Prince Louis.46

Less easily explained is the fact that although Magna Carta and the Forest Charter were both regularly confirmed during the course of the thirteenth century, the reference to elections in the former was never restored, and the Election Charter itself was never reconfirmed by an English king. The most obvious explanation for this is that it was not in the interests of the crown to do so. In addition, it had in some ways been superseded by the canons of the Fourth Lateran Council, issued in 1215, which included the ruling that any election resulting from the abuse of secular power was invalid.47 Furthermore, the charter was very much a product of its age – an age in which a trio of extremely forceful men had clashed over a debate which began to change once they were removed from the scene. Both Innocent III and King John died in 1216. Stephen Langton outlived them by over a decade, dying in 1228, and it is unlikely to be a coincidence that the charter received papal reconfirmation in January of that year;48 the elderly archbishop may well have requested that this be done, in a last attempt to protect the ecclesiastical liberties for which he had fought so hard.49 But by this stage, on many levels, the crisis had passed; electoral disputes continued, but elections were, for the most part, no longer the political minefield they had been fifteen years earlier.

More specifically, disputes over electoral practice increasingly focused on detailed disagreements over specific elections and the relative rights of the various parties involved. Partly as a result of John’s charter, the principle of electoral freedom became deeply entrenched in the national consciousness. By the 1270s, even the crown was confidently asserting that ‘elections ought to be free’.50 A hundred years earlier, it would have been unthinkable for a king to talk in such terms, but it had since become unremarkable. As a consequence of this shift in attitudes, some of the worst abuses of royal power – the things that had so enraged the church in the twelfth and very early thirteenth centuries – died out. Chapters were no longer denied licence to elect, so the lengthy vacancies that had occurred under the Angevins – most outrageously at Carlisle, which lacked a bishop for almost fifty years51 – were a thing of the past. Furthermore, elections were no longer held in the king’s chapel, instead taking place away from court in the cathedral chapter of the vacant see.

Of, course, John, Henry III and indeed all subsequent medieval kings of England still enjoyed a great deal of influence over episcopal appointments, but this does not mean that the charter was an empty concession with no subsequent importance. Inevitably, the clergy still complained about the conduct of elections. Intriguingly, they never seem to have pressured Henry to reconfirm the charter, but it was intermittently mentioned within the context of such disputes, and used a standard against which royal failings could be measured and condemned. For example, when the bishopric of Hereford fell vacant in 1240, Robert Grosseteste feared that the election would be characterized by ‘the oppressive malady of terror, threats, violent intimidation and bribery’; to prevent this, he recommended the clear and public exposition of John’s charter, and its papal confirmation.52 The charter was produced in 1253, during the negotiations leading up to the reconfirmation of Magna Carta.53 It was mentioned again at the 1257 council of the Canterbury province, which complained that Henry was seeking to control elections in a manner ‘contrary to the charter on elections which his father granted’,54 whilst a list of grievances that oppressed the land of England (1264) complains that the king frequently deprived the clergy of ‘the right of free election which by law they ought to have’.55

Even during the fourteenth centuries, as papal provision became the dominant, and eventually only, form of episcopal appointment, the charter retained some importance. It continued to be copied and cited: Edward II used the charter to defend his rights against the threat of papal provision,56 and as late as the early fifteenth century it was copied onto the close rolls of Henry IV.57 Even if the charter was initially a declaration of ecclesiastical liberties, in less than a century it had been completely subverted into a prop for royal rights over the English Church. As such, it was surely, one of John’s more useful legacies to his heirs – and certainly caused them far less trouble than Magna Carta.

Dr Katherine Harvey is the author of Episcopal Appointments in England, c.1214-1344: from episcopal election to papal provision (Farnham, 2014). She was awarded her PhD at King’s College London in 2012 and is now Associate Lecturer and Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London. Her current research, funded by a Society for Renaissance Studies Postdoctoral Fellowship, explores ‘Medicine and the Bishop in England, c.1350-c.1550’.

1 | For a more detailed account of the significance of the Freedom of Election charter and of episcopal elections in thirteenth and fourteenth-century England, see Katherine Harvey, Episcopal Appointments in England, c.1214-1344: From Episcopal Election to Papal Provision (Farnham, 2014) |

2 | English Historical Documents Vol. 2: 1042-1189, ed. D. C. Douglas & G. W. Greenaway (London, 1953), p. 721. |

3 | Anne Duggan, ‘Law and Practice in Episcopal and Abbatial Election before 1215: with special reference to England’ in Corinne Péneau (ed.), Élections et Pouvoirs Politiques du VIIe au XVIIe Siècle (Bordeaux, 2008). pp. 51-2. |

4 | Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France, ed. M. Bouquet et al., new edn directed by L. Delisle (19 vols, Paris, 1869-80), XVI, p. 645. The writ itself does not survive; the allegation that it was sent was made in writing by the Young King at the time of his rebellion against his father. |

5 | Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, ed. J. C. Robertson and J. B. Sheppard (7 vols, RS, 1875-85), VI, pp. 503-5. |

6 | Radulfi de Diceto Decani Lundoniensis Opera Historica, ed. W. Stubbs (2 vols, RS, 1876), I, p. 367. |

7 | Duggan, ‘Law and Practice’, pp. 53-5. |

8 | Magna Vita Sancti Hugonis, ed. D. L. Douie & H. Farmer (2 vols, London, 1961), I, pp. 71-2. |

9 | Christopher Cheney, From Becket to Langton: English Church Government 1170-1213 (Manchester, 1956), p. 23. |

10 | Ralph Turner, ‘Richard Lionheart and English Episcopal Elections’, Albion, 29 (1997), pp. 1-13. |

11 | For a detailed analysis of elections in England during the reign of King John, see Christopher Cheney, Pope Innocent III and England (Stuttgart, 1976), pp. 121-78. |

12 | Selected Letters of Pope Innocent III concerning England (1198-1216), ed. C. R. Cheney and W. H. Semple (London, 1953) [hereafter SLI], pp. 50-51 (no. 17). |

13 | For a fuller account of the election, see David Knowles, ‘The Canterbury Election of 1205-6’, EHR, 53 (1938), pp. 211-20. |

14 | SLI, pp. 86-90 (no. 29). |

15 | Memoriale Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs (2 vols, RS, 1872-73), II, p. 199; RLP, I, p. 74. |

16 | SLI, pp. 102-3 (no. 34). |

17 | W. L. Warren, King John (London, 1978), pp. 166-9; Christopher Harper-Bill, ‘John and the Church of Rome’ in Stephen Church (ed.), King John: New Interpretations (Woodbridge, 1999), pp. 289-315, at pp. 306-7. |

18 | SLI, pp. 115-16 (no. 38). |

19 | Warren, John, pp. 206-11. |

20 | SLI, pp. 166-7 (no. 62). |

21 | The Letters of Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) Concerning England and Wales: A Calendar, ed. C. R. Cheney and M. G. Cheney (Oxford, 1967) [hereafter CLI], no. 939. |

22 | CLI, nos. 938, 939. |

23 | CLI, no. 968; Memoriale Walteri de Coventria, II, p. 216; CM, II, p. 571. |

24 | Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum in Turri Londinensi asservati, ed. T. D. Hardy (2 vols, London, 1833-44), I, pp. 160a, 162a. |

25 | Matthæi Parisiensis, Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora, ed. H. R. Luard, RS, 57 (7 vols, London, 1872-83) [hereafter CM], II, p. 571; Maurice Powicke, Stephen Langton (Oxford, 1928), p. 105. |

26 | RLC, I, p. 160a. |

27 | Roger Wendover’s Flowers of History, ed. J. A. Giles (2 vols, London, 1849), II, pp. 292-30. |

28 | RLC, I, pp. 177b, 181b; Councils and Synods, with Other Documents Relating to the English Church (II: A.D. 1205-1313), ed. F. M. Powicke and C. R. Cheney (2 vols, Oxford, 1964) [hereafter C&S], I, p. 21. |

29 | The Register of the Diocese of Worcester during the vacancy of the see, usually called ‘Registrum sede vacante’, ed. J. Willis Blund, Worcestershire Historical Society, (Oxford, 1897), p. 105. |

30 | Henry Richardson and George Sayles, The Governance of Mediaeval England from the Conquest to Magna Carta (Edinburgh, 1963), p. 381. |

31 | ‘Saving to us and our heirs custody of vacant churches and monasteries which belong to us’. |

32 | Warren, John, pp. 224-6. |

33 | Everett Crosby, The King’s Bishops: The Politics of Patronage in England and Normandy, 1066-1216 (New York, 2013), p. 105. |

34 | CM, II, p. 571. |

35 | RLC, I, p. 179; Rotuli Litterarum Patentium in Turri Londinensi Asservati, ed. T. D. Hardy (London, 1835), I, p. 124; Rotuli Chartarum in Turri Londinensi Asservati, ed. T. D. Hardy (London, 1837), p. 202b; The Registrum Antiquissimum of the Cathedral Church of Lincoln, ed. C. Foster and K. Major, Lincoln Record Society, 27-9, 32, 34, 41-2, 46, 51, 62, 67-8 (10 vols, Hereford, 1931-75), I, p. 143. |

36 | For the prominence of the idea of compensation in the charter, see Cheney, Innocent III and England, p. 363. |

37 | Cheney, Innocent III and England, p. 262. |

38 | In late October, he was summoned to attend a great council on ecclesiastical affairs, which was to be held at Reading shortly after Christmas (RLC, I, p. 176), but by 16 November he had been recalled (RLC, I, pp. 177b, 181b; C&S, I, p. 21). |

39 | Memorials of St Edmund’s Abbey, ed. T. Arnold (3 vols, RS, 1890-96), II, p. 125; Cheney, Innocent III and England, pp. 364-5. |

40 | RLP, p. 123b; Rotuli Chartarum, 202b, 204b; Cheney, Innocent III and England, p. 365 n. 45. |

41 | SLI, pp. 198-201 (no. 76). |

42 | CM, II, pp. 606-7. |

43 | James Holt, Magna Carta, 2nd edn (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 448-51 (c. 1). |

44 | SLI, pp. 198-201 (no. 76). |

45 | Holt, Magna Carta, pp. 448-51. |

46 | David Carpenter, The Minority of Henry III (London, 1990), p. 23. |

47 | Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, ed. N. P. Tanner (2 vols, London, 1990), I, pp. 246-8 (cc. 23-6). |

48 | Concilia Magnae Brittanniae et Hiberniae, ed. D. Wilkins (4 vols, London, 1737), I, p. 621. |

49 | The literature on Langton’s contribution to Magna Carta is too extensive to cite in full here, but for recent discussions, see John Baldwin, ‘Master Stephen Langton, Future Archbishop of Canterbury: The Paris Schools and Magna Carta’, EHR, 123 (2008), pp. 811-46; Nicholas Vincent, ‘Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury’ in Louis-Jacques Bataillon, Nicole Bériou, Gilbert Dahan and Riccardo Quinto (eds), Étienne Langton: Prédicateur, Bibliste, Théologien (Turnhout, 2010), pp. 51-123; David Carpenter, ‘Archbishop Langton and Magna Carta: His Contribution, His Doubts and His Hypocrisy’, EHR, 126 (2011), pp. 1041-65. |

50 | ‘First Statute of Westminster’, c. 5 in The Statutes of the Realm (11 vols in 12, London, 1810-28), I, p. 28. |

51 | 1156/7-1203. Paulinus of Leeds was elected in 1186, at the request of Henry II, but refused. Bernard of Ragusa’s appointment was probably the result of papal intervention. See EEA 30: Carlisle, 1133-1192, ed. D. M. Smith (Oxford, 2005), pp. xxxv-xxxviii, for the exceptional circumstances behind this uniquely long vacancy. |

52 | The Letters of Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, ed. F. A. C. Mantello and J. Goering (Toronto, 2010), pp. 283-5 (letter 83). |

53 | Cronica Johannis de Oxenedes, ed. H. Ellis (RS, 1859), pp. 196-7. The Chronica Majora, on which Wallingford’s chronicle was based, omits this detail; see CM, V, p. 377. For the relationship between the two chronicles, see R. Vaughan, ‘The Chronicle of John of Wallingford’, EHR, 73 (1958), pp. 66-70. |

54 | C&S, I, pp. 539-40. |

55 | Documents of the Baronial Movement of Reform and Rebellion, 1258-67, ed. R. F. Treharne and I. J. Sanders (Oxford, 1973), p. 271. |

56 | Reg. Sede Vacante, pp. 104-7. |

57 | CCR 1405-1409, p. 410. |

Referenced in

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta (Features of the Month)

John grants freedom of election (The Itinerary of King John)

John's fears of French invasion abate (The Itinerary of King John)

The matter of episcopal elections (The Itinerary of King John)

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265