Dating the Outbreak of Civil War, April-May 1215

April 2015,

Thus far, week by week, we have found the King, as late as Easter 1215 and beyond, garrisoning his castles and making provision against unrest, without as yet any firm indication that a state of war was assumed to exist. Beginning on 15 April we have notice of safe conducts for various unnamed but nonetheless perhaps baronial parties that first the bishop of Winchester, and then on 23 April Archbishop Langton, were expected to bring with them to meet the King, such safe conducts being extended on 23 April to last to the feast of the Ascension (28 May).1 This chronology, obtained principally from chancery sources, has now to be reconciled with that offered by the chroniclers. Here, the Crowland chronicler ('Walter of Coventry') and Roger of Wendover supply the most detailed accounts. Crowland (below no.1) refers to the King's taking the Cross on 4 March. Thereafter, the barons, hearing that the King had summoned foreigners to his aid, and despairing of the negotiations that since January 1215 had been timed to resume at Northampton on the Sunday after Easter (i.e. 26 April), met at an unspecified location and from there obtained an unsatisfactory response from the King. As a result, they returned to their homes to fortify their castles and prepare for combat.2 Only later, according to Crowland, did the barons reassemble at Stamford, in the week after Easter. Negotiations were held via go-betweens, with the King at this time established near Oxford. Papal letters were delivered both to the King and to Archbishop Langton in an attempt to secure peace. From their last conference at Brackley, the barons then rode back to Northampton, in arms and with banners, having diffidated the King and repudiated their homages. By such means was war declared.

Crowland's chronology here is plausible, but contains what appears to be at least one serious mistake. The papal letters to which he refers can be identified with those dated 19 March preserved on the dorse of the Patent Roll, on a membrane of the roll whose face records letters of 17-25 May, suggesting that they were received after, rather than before the baronial defiance.3 In confirmation of mid May rather than late April as the date of their publication, the King's response to these letters is dated 29 May, a full month later than Crowland might lead us to expect.4 In further and apparently definitive confirmation, the Pope himself, writing in August 1215 as part of his bull annulling the settlement agreed at Runnymede, set out a detailed narrative of events since 1213, including a lengthy account of the letters he had dispatched both to the King and the barons on 19 March. In this, he specifically states that the messengers carrying the letters of 19 March did not arrive in England until after the barons had thrown off their homage and declared war. The implication offered in August seems to be that the Pope's peace proposals of 19 March arrived in England after the baronial diffidation, but before the fall of London on 17 May. This supplies a chronology that fits very neatly with the copying of the letters of 19 March onto the Patent Roll, shortly after 17 May.5

There is an alternative possibility here. The papal letters may have been copied onto the Patent Roll in late May only because it was then that the King began to compose a response to them. They could in theory have been received several weeks previously. Certainly, the delay between their issue and their arrival in England - five weeks if we assume publication in the week beginning 19 April, a much less plausible nine weeks if we are to assume publication only around 20 May - was remarkably protracted. Could it have been that the Pope was deliberately misinformed as to the chronology, and that the baronial decision to go to war was indeed in part inspired by the papal letters of 19 March, in effect depriving the barons of any real hope that by keeping the peace, they might still expect support from Rome? This is just about possible. It nonetheless remains conjecture and very far from established fact.6

Wendover's account (below no.2) supplies a slightly less complex chronology. Like the Crowland chronicler, Wendover reports that the barons met at Stamford in Easter week (20-26 April). At this time, he claims, the King was at Oxford. This is a mistake. In reality, the King was at Oxford from 7-13 April, where we have found him, on Palm Sunday (13 April), in company with Archbishop Langton and at least two of the future rebel leaders.7 By Easter week, he had moved to London, making no further visit to Oxford before July 1215. Wendover's narrative them passes to Monday 27 April, by which time the barons were at Brackley. Naming forty-four of the baronial leaders, Wendover claims that the King sent Archbishop Langton, William Marshal earl of Pembroke, 'and several others', in order to hear the baronial demands. The barons, who had acquired the support of Langton (a detail already implied in Wendover's account of events earlier in 1214), now presented a written schedule of their terms, including the restoration of ancient laws and customs whose refusal, they warned, would result in the violent seizure of the King's castles and lands. Langton duly reported these demands to the King, but was met with derision and fury. This despite the fact that the laws and liberties were not, as the King claimed, contrary to reason, but derived for the most part either from the coronation charter of Henry I or from the 'Laws of Edward the Confessor'. The barons, learning of this refusal, and appointing Robert fitz Walter as leader of their army, with the title 'Marshal of the army of God and Holy Church', then marched upon Northampton. Lacking siege engines, they wasted two weeks there in a fruitless attempt to seize the King's castle.

Thus far, we learn of baronial meetings, apparently before Easter (Crowland, referring to an unspecified location), then in Easter week at Stamford, and on 27 April at Brackley (Wendover). Negotiations with the King continued, according to Crowland, whilst the court was 'near Oxford'. Wendover, although misdating the King's visit to Oxford, confirms that Oxford, or at least the region between Brackley and the Thames, was central to negotiations. To this, the annals of Dunstable (below no.3) add a further detail, stating that the baronial diffidation of the King, agreed at Brackley, was delivered at Wallingford by 'a certain canon originating from Dereham' (de Derham oriundus). Here at last we can map the baronial negotiations on to the King's itinerary, since the King was undoubtedly at Wallingford from Thursday 30 April to Saturday 2 May, and thereafter at Reading from Saturday 2 to Wednesday 6 May. Wallingford, and for that matter Reading, are both sufficiently close to Oxford to correspond to the Crowland chronicler's reference to the King being at this time established 'circam Oxoniam'.

The Dunstable annalist's reference to the baronial diffidation being delivered at Wallingford (presumably between 30 April and 2 May) by a canon 'originating from Dereham' might incline us to invoke the name of Master Elias, the most famous son of West Dereham in Norfolk. Elias served as steward to Archbishop Langton and in due course as one of the most active figures both in the publication of Magna Carta and in the subsequent baronial alliance with Louis of France.8 By 1215, Master Elias was a canon of Lincoln Cathedral.9 Nonetheless, the Dunstable annalist's reference to 'a canon originating from Dereham' seems more likely to refer to a regular canon of either the Augustinian or Premonstratensian order, with a Premonstratensian canon of Dereham Priory as the most obvious fit. Here, the annals of Southwark (below no.4a), yet another piece in our jigsaw, supply two dates missing in other sources: the outbreak of war dated to 3 May, and the baronial diffidation, said to have been delivered at Reading (not Wallingford) on 5 May. This defiance, according to the Southwark annals, was pronounced 'by a black canon' (quendam canonicum nigrum). These same details, including the 'black canon', reappear in a London rewriting of the Southwark/Merton annals (below no.4b), from c.1270, adding further circumstantial details (some of them perhaps derived at second hand from Wendover), and demonstrating a particular interest in Geoffrey de Mandeville, here said to have been appointed as one of the marshals (plural) alongside Robert fitz Walter, as commander of the baronial army.10

This, I believe, settles the matter of Elias of Dereham. Certainly, to place Master Elias so firmly within the baronial camp as early as May 1215 would be to assume, in accordance with Wendover's claims, that Archbishop Langton, Elias's chief employer, was already by this time firmly identified with the baronial party. On the contrary, so far as can be established, Langton continued to be treated as a neutral mediator as late as Runnymede and into July 1215. Had it been Elias who delivered the baronial challenge to the King, it is difficult to imagine circumstances in which Elias, again as late as July 1215, could have been entrusted in chancery with the distribution of copies of Magna Carta, apparently still serving as an agent of the theoretically neutral Archbishop. As for the diffidation, delivery by a regular canon rather than by a clerk was more likely to guarantee the deliverer against future reprisals. We can perhaps square the accounts in Dunstable and Southwark/London by supposing that the canon arrived first at Wallingford on 3 or 4 May, but did not properly catch up with the King until Reading, on the 5th. There is, even so, one detail that is signally missing here. In 1264, when the barons of King John's son publicly diffidated King Henry III before the battle of Lewes, they were answered by a corresponding diffidation issued in the name of the King. In other words, there was a reciprocal declaration of war. In 1215, no such reciprocity can be assumed. Perhaps, even now, the King hoped that by withholding his acknowledgement of the baronial declaration of war, war itself might still be avoided.

There remain a few further details to Wendover's narrative that demand clarification. Wendover names forty-four men as 'principal inciters' of rebellion (described by Wendover as 'this plague'). His list was copied by Matthew Paris, with virtually no changes save that Paris tones down 'plague' to 'presumption' and adds a further, forty-fifth name, that of Conan son of Elias. Wendover's list includes nineteen of the future twenty-five barons of Magna Carta (Robert fitz Walter, Eustace de Vescy, Richard de Percy, Robert de Ros, Saher de Quincy, Richard de Clare, Henry de Bohun (here misidentified as H. earl of Clare), Roger Bigod, William de Mowbray, Robert de Vere, William Malet, William Marshal the younger, Roger de Montbegon, John fitz Robert, Richard de Montfichet, William de Lanvallay, Geoffrey de Mandeville and William of Huntingfield, and John de Lacy). It nonetheless omits the names of six others who in due course appear in lists of the twenty-five (William de Forz count of Aumale, Gilbert de Clare, the mayor of London, Geoffrey de Say, William d'Aubigny of Belvoir and Hugh Bigod).11 Apart from the mistaken identification of Henry de Bohun as 'H. earl of Clare', Wendover's list includes at least two names that seem to be misplaced: O. fitz Alan, and G(?eoffrey) constable of Melton. Geoffrey, of Melton Constable in Norfolk, hereditary constable of the bishops of Norfolk, is nowhere else recorded as a rebel and, indeed, appears in receipt of instructions from the King even at the height of civil war. His name has perhaps been included here by mistake for that of William d'Aubigny, constable of Belvoir.12 'O. fitz Alan' makes no other appearance in the records, and may be assumed to be either a mistaken identification or a recopying of the name of John fitz Alan, undoubtedly a rebel, who appears elsewhere in Wendover's list.

To sum up, then, from our various sources, we arrive at the following chronologies for King and barons:

20-26 April King at London 20-23 April moving thereafter via Kingston-Alton-Clarendon

Barons meet at Stamford

27 April Barons at Brackley.

News of their meeting communicated to the King

28 April-2 May Shuttle diplomacy between Brackley and the King's court, itself at Corfe (27-28

April), moving via Clarendon and Marlborough (28-30 April) to Wallingford (30

April-2 May)

2-6 May King at Reading

3 May Barons defy the King and move against Northampton. Messengers sent to the King

at Wallingford

3-c.15 May Baronial siege of Northampton

5 May Baronial defiance delivered to the King at Reading by a canon of Dereham

c.16 May Barons move south via Bedford and Ware

17 May Baronial seizure of London. At about this time, the arrival of the papal letters of 19

March attempting mediation, now overtaken by events

1. The Crowland Chronicler's report of the outbreak of civil war.

The Crowland/Barnwell chronicler, in Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols. (London, 1872-73), ii, 219-20.

Igitur in hebdomada Paschali conuenerunt in manu valida ex condicto apud Stamforde et quoniam ex Aquilonaribus partibus pro parte maiori venerant, vocati sunt adhuc Aquilonares. Inde profecti sunt Norhamtonam, nihil quidem adhuc hostile gerentes, preter solum apparatum bellicum. Iunxerunt autem se eis Egidius episcopus Herefordensis, Gaufridus de Mandeuilla, Robertus filius Walteri et plures alii, et hii potissimum qui aliquid aduersum regem habebant. Interim rex eos per plurimos internuncios reuocare studebat, habitaque sunt inter eos colloquia multa per archiepiscopum, episcopos et alios magnates, rege circa Oxoniam commorante. Ibi presentate sunt littere domini pape pro baronibus regi in quibus monebatur eorum iustas audire petitiones, et alie pro rege archiepiscopo in quibus precipiebatur omnes conspirationes vel coniurationes contra regem factas auctoritate apostolica cassare, et ne de cetero fierent alique eadem auctoritate inhibere. Ultimo autem colloquio, quod erat non longe a Brackele, regem diffiduciantes per internuncios, et hominia sua reddentes, reuersi sunt Northamptonam armati, et aciem ordinatam precedentibus vexillis.

Therefore in Easter week, as agreed, they gathered in strength at Stamford, with a majority coming from the northern parts, known already as 'The Northerners'. Thence, they set out for Northampton, thus far without any of them showing open hostility, save only for their warlike equipment. Giles bishop of Hereford, Geoffrey de Mandeville, Robert fitz Walter and many others joined them, and those who had powerful grievance against the King. Meanwhile, the King, using several go-betweens, sought to win them back, and many discussions were held between the parties via the archbishop, the bishop and other magnates, the King at this time staying near Oxford. Here were presented the letters of the Pope addressed to the King on behalf of the barons in which he was advised to listen to their just requests, and other letters to the archbishop on behalf of the King in which he was commanded to quash by apostolic authority all conspiracies or cabals made against the King and by the same authority to forbid any such in future. However, from their last meeting held near Brackley, diffidating the King by messengers and renouncing their homage, the barons returned in arms to Northampton, in military order and with banners going before them.

2. Roger of Wendover's account of these same events.

Wendover, Flores Historiarum, ed. H.O. Coxe, 4 vols. (London, 1842), iii, 297-9. Here noting the principal variants from Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard, 7 vols (London, 1872–83), ii, 585-6. The translation is my own, although with occasional glances at that by J.A. Giles, Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History (London, 1849), ii, 305-6.

De principalibus exactoribus legum et libertatum:

Per idem tempus, in hebdomada Pasche, conuenerunt apud Stamford magnates sepedicti cum equis et armis, qui iam in sui fauorem uniuersam fere totius regni nobilitatem attraxerant, et exercitum inestimabilem confecerunt <eo maxime quod rex exosum semper se omnibus exhibuit>. Estimati sunt namque in exercitu illo duo millia militum, preter equites, seruientes et pedites, qui armis erant variis premuniti. Fuerunt autem principales huius pestis incentores: Robertus filius Walteri, Eustachius de Vesci, Richardus de Perci, Robertus de Ros, Petrus de Bruis, Nicolaus de Stuteuilla, Saerus comes Wintoniensis, R(icardus) comes de Clare, H. comes Clarensis, Rogerus comes Bigod, Willelmus de Munbray, Rogerus de Creissi, Ranulphus filius Roberti, Robertus de Ver, Fulco filius Warini, Willelmus Mallet, Willelmus de Monte Acuto, Willelmus de Bellocampo, S(imon) de Kime, Willelmus iuuenis Mareschallus, Willelmus Maudut, Rogerus de Monte Begonis, Iohannes filius Roberti, Iohannes filius Alani, G(ilbertus) de Laual, O. filius Alani, W(illelmus) de Hobregge, O(liuerus) de Vallibus, G(ilbertus) de Gant, Mauritius de Gant, R(icardus) de Brackele, R(icardus) de Muntfichet, W(illelmus) de Lanualei, G(aufridus) de Mandeuilla comes Essexie, Willelmus frater eius, Willelmus de Huntingefeld, Robertus de Greslei, G. constabularius de Meautum, Alexander de Puinter, Petrus filius Iohannis, Alexander de Sutuna, Osbertus de Bobi, Iohannes constabularius Cestrie, Thomas de Mulutune, <Conanus fitz Elias> et multi alii. Isti omnes (Paris supplies communes) coniurati et confederati, Stephanum Cantuariensem archiepiscopum capitalem consentaneum habuerunt. Erat autem rex eo tempore apud Oxoniam magnatum exspectans aduentum. Igitur die Lune proxima post octauas Pasche barones memorati in villa de Brackeleia pariter conuenerunt, quod cum esset a rege compertum, misit ad eos archiepiscopum Cantuariensem et Willelmum Mareschallum comitem de Penbroc cum aliis quibusdam viris prudentibus, sciscitans ab eis que essent leges et libertates quas querebant. At illi nuntiis prelibatis schedulam quandam porrexerunt que ex parte maxima leges antiquas et regni consuetudines continebat, affirmantes quod, nisi rex illas incontinenti concederet et sigilli munimine confirmaret, ipsi per captionem castrorum suorum, terrarum et possessionum, ipsum regem compellerent, donec super premissis sibi satisfaceret competenter. Tunc archiepiscopus cum sociis suis schedulam illam ad regem deferens, capitula singula coram ipso memoriter recitauit. Rex autem cum capitulorum tenorem intellexisset, cum indignatione maxime subridens ait: "Et quare cum istis iniquis exactionibus barones non postulant regnum? Vana sunt", inquit, "et superstitiosa que petunt, nec aliquo rationis titulo fulciuntur". Affirmauit tandem cum iuramento furibundus, quod nunquam tales illis concederet libertates, unde ipse efficeretur seruus. Capitula quoque legum et libertatum que ibi magnates confirmai querebant, partim in charta regis Henrici paulo superius scripta sunt, partimque ex legibus regis Edwardi antiquis excerpta, sicut sequens historia suo tempore declarabit.

De obsidione castelli de Norhantona facta a baronibus:

Cum itaque archiepiscopus et Willelmus Mareschallus regem ad consensum inducere nullatenus potuissent, ad iussionem regis ad barones reuersi, omnia que a rege audierant per ordinem retulerunt, que cum magnates cognouissent constituerunt Robertum filium Walteri principem militie sue, appelantes eum "Mareschallum exercitus Dei et sancte ecclesie", et sic singuli ad arma conuolantes, versus Norhantunam acies direxerunt. Quo cum peruenissent, illico castrum obsidione vallauerunt, cumque per dies quindecim inaniter ibidem moram protraxissent, et paru(u)m, immo nihil, omnino profecissent, castra inde mouere decreuerunt, nempe absque petrariis et aliis bellicis instrumentis aduenientes non sine confusione, infecto negotio, ad castrum de Bedefordt perrexerunt, veruntamen in obsidione predicta vexillifer Roberti filii Walteri cum quibusdam aliis, capite spiculo baliste terebrato, non sine dolore multorum interiit.

Concerning the principal demanders of laws and liberties: At this time, in Easter week, the aforesaid magnates gathered at Stamford13 with horses and arms, having attracted to their cause almost all of the nobility of the whole realm, making an army of inestimable size <doing this, above all, because the King had always shown them such hatred>. For there were judged to be in that army two thousand knights, not counting horse soldiers, serjeants and infantrymen, variously equipped with weapons. The principal inciters of this plague14 were Robert fitz Walter, Eustace de Vescy, Richard de Percy, Robert de Ros, Peter de Brus, Nicholas de Stuteville, Saher (de Quincy) earl of Winchester, R(ichard) earl of Clare, H. earl of Clare (?recte H(enry de Bohun) earl of Hereford)15, Roger Bigod earl (of Norfolk), William de Mowbray, Roger de Cressy, Ranulph fitz Robert, Robert de Vere, Fulk fitz Warin, William Malet, William de Montacute, William de Beauchamp, S(imon) de Kyme, William Marshal the younger, William Mauduit, Roger de Montbegon, John fitz Robert, John fitz Alan, G(ilbert) de Laval, O. fitz Alan (sic), W(illiam) of Howbridge, O(liver) de Vaux, G(ibert) de Gant, Maurice de Gant, R(ichard) of Brackley, R(ichard) de Montfichet, W(illiam) de Lanvallay, G(eoffrey) de Mandeville earl of Essex, William (de Mandeville) his brother, William of Huntingfield, Robert de Gresley, G(?eoffrey) constable of Melton, Alexander of Pointon, Peter fitz John, Alexander of Sutton, Osbert of Boothby, John (de Lacy) constable of Chester, Thomas of Moulton, <Conan son of Elias> and many others. Bound together by oaths, they had as their chief collaborator Stephen archbishop of Canterbury. The King was at this time at Oxford, expecting the arrival of the magnates. Therefore on the Monday after the octaves of Easter (27 April 1215), the said barons met together in the vill of Brackley. Learning of this, the King sent to them the archbishop of Canterbury and William Marshal earl of Pembroke together with other wise men, seeking to learn from them what laws and liberties they sought. The barons handed over a certain schedule to the aforesaid messengers, for the most part setting out the ancient laws and customs of the realm, affirming that unless the King immediately acknowledged these and confirmed them under the authority of his seal, they would compel the king through the seizure of his castles, lands and possessions, until he had adequately satisfied their demands. The archbishop, together his associates, brought that schedule to the King and recited each of its chapters learned by heart before the King. However, the King, having understood the contents of each chapter, replied, derisively and with the greatest indignation: "And since the barons seek such unjust demands, why don't they ask for the kingdom itself? These things that they seek are vain and make-believe, unentitled to any claim by reason". And at length he declared, with a furious oath, that he would never concede such liberties whereby he himself would be rendered a slave. Nonetheless, the chapters of laws and liberties that the magnates here sought confirmed were taken partly from the charter of King Henry I, set out above, partly from the ancient laws of King Edward, as the following history will show in due time.

Concerning the siege of Northampton Castle undertaken by the barons:

Following the failure of the archbishop and of William Marshal to persuade the King to agree, the King sent them back to the barons to whom they recounted everything that they had heard from the King. When the barons learned this, they appointed Robert fitz Walter as leader of their army, calling him "Marshal of the army of God and Holy Church". And so, with each of them rushing to arms, the barons directed their force towards Northampton. There, they at once lay siege to the castle. But having lingered there for fifteen days pointlessly, achieving little or nothing, they determined to move their camp. For having come without petraries or other war machines, with their purpose unachieved, they proceeded to Bedford Castle. In the aforesaid siege (of Northampton), the standard bearer of Robert fitz Walter died, alongside various others, pierced through the head by a crossbow bolt, to the grief of many.

3. The Account of these events in the Dunstable Annals.

Annales Monastici, ed. H.R. Luard, 5 vols. (London, 1864-9), iii (Dunstable), 43.

Eodem anno barones Norenses cum Galensibus et Scotis conquerentes de nimia regis oppressione conspirauerunt contra regem, et in ebdomada Paschae conuenerunt apud Norhamtone, sed castrum volentes capere non profecerunt. Inde per conniuentiam quorundam, Dominica ante festum sancti Dunstani totam ciuitatem Londoniarum occuparunt preter turrim .... Tandem apud Runnymede conuenerunt, et die Geruasii et Protasii facta est ibidem pax inter regem et barones, que paruo tempore optinuit. Et recepit ibi rex homagia que barones ei in principio guerre reddiderant, in diffidatione facta apud Walingefort per quendam canonicum de Derham oriundum.

In the same year, the northern barons, together with the Welsh and the Scots, complaining against the King's harsh oppression, conspired against him, and in Easter week they gathered at Northampton, but were unable to take the castle as they had hoped. Thereafter, with the connivance of others, on the Sunday before the feast of St Dunstan (17 May) they occupied the whole city of London save for the Tower .... At length, they met at Runnymede, and on the feast day of SS Gervasius and Protasius (19 June) peace was made there between the King and the barons, that endured only briefly. And the King received there the homage that the barons had repudiated at the start of the war, in the diffidation made at Wallingford via a certain canon originating from Dereham.

4a. The Account of these events in the Annals of Southwark (and Merton).

BL ms. Cotton Faustina A viii (Southwark Annals) fo.140r (139r, p.199), whence M. Tyson, 'The Annals of Southwark and Merton', Surrey Archaeological Collections, xxxvi (1925), 49. Here supplied from the manuscript, using the printed edition only for the Merton variants.

Hoc anno orta est guerra inter Iohannem regem Anglie et barones Norrenses circa festum Inuencionis Sancte Crucis quia noluit16 iura sua que promiserat firmiter persoluere. Hunc etiam regem diffid(ar)e fecerunt per quendam canonicum nigrum apud Rading' in vigilia sancti Iohannis ante Portam Latinam.

In this year (1215), war broke out between John King of England and the northern barons around the feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross (3 May), because the King refused firmly to uphold their rights which he had promised. Here moreover, the barons diffidated the King via a certain black canon at Reading on the vigil of the feast of St John before the Lateran Gate (5 May).

4b. The Account of these events in the closely related London Annals (by Arnold FitzThedmar, c.1270)

London, Metropolitan Archives CLA/CS/01/001/001 fo.37v, whence De Antiquis legibus liber. Cronica maiorum et vicecomitum Londoniarum, ed. T. Stapleton, Camden Society xxxiv (1846), 201. Below printing in smaller type the words merely repeated from Southwark. For Ian Stone's comments on this rewriting of Southwark, see above n.8.

Eodem anno orta est gwerra inter ipsum regem et barones suos circa festum Inuencionis Sancte Crucis, quia ipse noluit permittere eos uti libertatibus suis quas habuerunt per cartas predecessorum suorum regum Anglie. Qui vero barones, licet fuissent de diuersis partibus regni Anglie, tamen omnes fuerunt vocati Norenses, qui in vigilia sancti Iohannis ante Portam Latinam diffidare fecerunt eundem regem per quendam canonicum nigrum apud Redinges. Ipse autem fecerunt Robertum filium Walteri et Galfridum de Mandeuile marescallos exercitus eorum, quem exercitum ipsi vocauerunt exercitum Dei.

In this year (1215), war broke out between the aforesaid King and his barons around the feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross (3 May), because the King refused to allow them to enjoy their liberties which they had by charters of his predecessors, the kings of England. And these barons, despite coming from various parts of the realm of England, were collectively called 'the Northerners', and they diffidated the King via a certain black canon at Reading on the vigil of the feast of St John before the Lateran Gate (5 May). They also made Robert fitz Walter and Geoffrey de Mandeville marshals of their army, which army they named "the army of God".

1 | RLP, 133, 134. |

2 | Translated in the Feature of the Month, 'The King Takes the Cross'. |

3 | For the papal letters here, both of 19 March, see Selected Letters of Pope Innocent III concerning England (1198-1216), ed. C.R. Cheney and W. H. Semple (London, 1953), 194-7 nos 74-5, as noted above 11-17 January (Sophie supply cross reference), the letters to the King here being known only from their mention in corresponding letters to the barons. For their enrolment, RLP, 141, whence Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 127. |

4 | Foedera, 129, from the dorse of the close roll, RLC, i, 268b, from a membrane (m.32, whence RLC, i, 213b-14b) that does indeed report royal letters of 27 May to 16 June. |

5 | Innocent's bull 'Etsi karissimus' of 24 August, as in Foedera, 135-6 ('Verum antequam nuncii cum hoc prouido et iusto mandato rediissent, illi iuramento fidelitatis omnino contempto ...... vassalli contra dominum et milites contra regem publice coniurantes, non solum cum aliis sed sum eius manifestissimis inimicis presumpserunt contra eum arma mouere, occupantes et deuastantes terras ipsius, ita quod ciuitatem quoque London' que sedes est regni proditorie sibi traditam inuaserunt. Interim autem prefatis nunciis reuertentibus, rex obtulit eis ... iusticie plenitudinem exhibere'). |

6 | Much of the preceding discussion is informed by discussion with David Carpenter. The King did indeed write to the Pope in the week beginning 19 April. But his letters take the form of a learned defense of Master Alexander of St Albans, and make no mention of the receipt of any recent papal bull denouncing conspiracy or urging the King to do justice: RLC, i, 203-3b, the subject of a forthcoming feature by Julie Barrau. The failure here to refer to something as important as the papal letters of 19 March would surely be remarkable if the letters had indeed already been received and published. |

7 | See Diary and Itinerary for the weeks 5-11 April and 12-18 April. Wendover's account here seems to have misled Kathleen Major ('Itinerary', in Acta Stephani Langton Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi AD 1207-1228, ed. K. Major, Canterbury and York Society l (1950), 165) into supposing that Langton shuttled between Brackley and the King at Oxford, on or after 20 April. In reality, this shuttle diplomacy should be redated on and after 27 April. |

8 | For his career in general, see Nicholas Vincent, 'Master Elias of Dereham (d.1245): A Reassessment', The Church and Learning in Later Medieval Society: Essays in Honour of R.B. Dobson, ed. C.M. Barron and J. Stratford (Donnington, 2002), 128-59. |

9 | John Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300, revised edition by D.E. Greenway (London, 1968-), iii, 73. |

10 | I owe to Ian Stone, who is presently re-editing this London chronicle, the knowledge that this section of the London annals is written in the hand of Arnold FitzThedmar, confidently dated to 1270. Mr Stone points out that Arnold's newly inserted reference to charters of John's ancestors might reflect the particular interests of the Londoners in such charters, just as Arnold's determination to specify that the 'Northerners' were by no means all truly northern chimes with his emphasis upon the role of the local baronial leaders, Robert fitz Walter and Geoffrey de Mandeville. |

11 | For lists of the twenty-five, see C.R. Cheney, ‘The Twenty-Five Barons of Magna Carta’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, l (1968), 280–307; J. C. Holt, Magna Carta (2nd ed., Cambridge, 1992), 479, and the article by Matthew Strickland, ‘Enforcers of Magna Carta (act.1215–1216)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, Oct 2005; online edn., Sept 2014 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/theme/93691, accessed 26 April 2015]. |

12 | For instructions to G(eoffrey) constable of Melton, from July 1217, see RLC, i, 314, 322. |

13 | As noted in Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. Luard, ii, 585 n.2, Paris subsequently substituted Brackley here, in his Historia Anglorum. |

14 | Paris here substitutes the word 'presumption' (presumptionis) for Wendover's 'plague' (pestis). |

15 | The correction here was first suggested by Luard (Paris, Chronica Majora, ii, 585 n.4) |

16 | The closely related Merton Annals, as noted by Tyson (p.49n.), here supply a slightly different form of words: 'noluit reddere eis iura sua sicut eis firmiter promiserat. Qui fecerunt diffidere ipsum regem per ...' |

Referenced in

Papal Letters of 19 March (Features of the Month)

Papal Letters of 19 March (Features of the Month)

The Outbreak of War (The Itinerary of King John)

'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers' (The Itinerary of King John)

'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers' (The Itinerary of King John)

'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers' (The Itinerary of King John)

'our barons who are against us' (The Itinerary of King John)

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

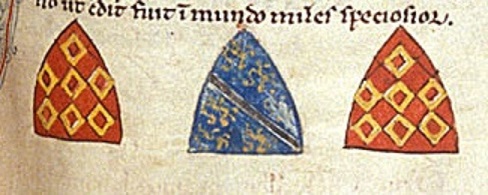

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265