'our barons who are against us'

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

3-6 May 1215 |

RC, 206b; RLP, 134b-5; RLC, i, 198b-9 |

||

7-9 May 1215 |

RC, 207; Cal.Chart.R. 1427-1516, 284-5; RLP, 135, 141; RLC, i, 199-9b, 204 |

Having met at Brackley in the previous week, the barons delivered their diffidation to the King before moving against the royal castle at Northampton. Their message to John was carried by a canon of West Dereham Priory in Norfolk sent first to Wallingford where he arrived on Sunday 3 May. The King, however, had left Wallingford the night before so that it was perhaps not until Tuesday 5 May, at Reading, that the baronial defiance was at last delivered.1 The barons now settled down to their siege of Northampton. The King had various options. The most obvious was for him to accept the baronial defiance and in turn to declare the barons to be his public enemies, cut off from all ties of fealty or lordly obligation. This was precisely what was to happen, fifty years later, in May 1264, when the barons came to diffidate John's son, King Henry III.2 In 1215, by contrast, John seems to have issued no matching defiance. Indeed, the chancery rolls avoid all mention of the rebels for at least a week after the delivery of their messages. The first that we hear of them from the King's own letters comes on Sunday 10 May, when they are referred to not as public enemies but as 'our barons who are against us' (barones nostri qui contra nos sunt), the possessive adjective here (nostri) implying that whatever the barons themselves might wish, the King most definitely had not divested himself of his claims to serve as their lord.3 Not for a further two days, until 12 May, were the rebels openly referred to as 'our enemies' (inimici nostri), in letters commanding the seizure of their lands.4

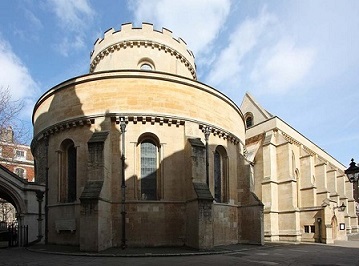

In the meantime, the chancery rolls supply only oblique evidence that the affairs of the realm had entered a new and more aggressive phase. Indeed, far from suggesting any new atmosphere of panic, the rolls for this week preserve by far the largest collection of routine royal charters issued since the previous autumn: eight instruments in all, including three charters of privilege for the Templars (no doubt in return for the hospitality that was afforded the King in the Temple precinct at London), a grant of trading privileges to the men of Swansea (the first of Swansea's borough charters), general confirmations to the monks of Welbeck and (William Brewer's Cistercian foundation at) Dunkeswell, and a routine exchange involving property in Nottinghamshire.5 The witness list to these charters show the King attended by three royalist bishops (Winchester, Worcester and Coventry), and at least three earls (William Marshal earl of Pembroke, William earl Warenne, William of Salisbury, and the would-be earl of Cornwall, Henry fitz Count). All of these men were involved, this week or the next, in attempts to forestall the coming storm.

On 5 May, the Marshal was sent into the country with letters to the constables of the bishop of Lincoln to admit him to their castles, the castle at Newark on Trent being perhaps the most crucial in communications between north and south. Similar letters were issued to royal constables elsewhere for the Marshal and the earls of Warenne and Salisbury.6 The Marshal was also crucial to the defence of the southern Marches, where he was empowered to collect two horn crossbows from the constable of Gloucester.7 Elsewhere, military preparations continued. On 4 May, the constable of Oxford, Ralph de Normanville, was called upon to leave his sons and other men in Oxford castle and to attend the King in person, whether for the King's defence or because Ralph's own loyalty was now suspect is not made clear.8 On the same day, and once again ignoring all claims by Hugh of Northwold to have been elected as abbot of Bury St Edmunds, the King commanded the knights of the abbey to take charge of the town of Bury and obey the King's own bailiff, John of Cornard. 9 The men of Norwich were likewise ordered to assist with the preparation of Norwich castle to resist attack.10 On the same day, 200 marks were commanded from the treasury to help the mayor and barons of London in the fortification of their city, timber was commanded for the defence of the castle at Old Sarum, and defensive measures were ordered for Marlborough.11 Orders were subsequently dispatched for the defence of Winchester castle under the supervision of Thierry the Teuton, constable of Berkhamsted, and for the renewal of the ancient custom whereby the men of Berkshire were deemed responsible for maintaining the moat of the castle at Wallingford.12 The town of Stafford was fortified, and perhaps most worryingly of all, instructions were sent for the provisioning of Geoffrey de Canville's castle at Launceston in Cornwall, from supplies then held at Bristol.13 This confirms the report of the Barnwell chronicler that trouble was now brewing in the south west, with a baronial siege about to be attempted against the city of Exeter.14

On 5 May, the day on which news of the baronial defiance at last seems to have reached the King, the prior of Daventry was sent overseas as the King's envoy, perhaps to the Pope. Certainly, from his base in Northamptonshire, the prior would have had first-hand knowledge of the recent baronial muster.15 To the Pope, the King wrote in conciliatory terms on 7 May. An earlier attempt to secure the election as bishop of Durham of the King's half-brother, Morgan provost of Beverley, had been resisted by John. The King now wrote to announce that he had relaxed his objections and that, should the Pope approve it, the provost's election could now be confirmed.16 A flurry of orders concerning the affairs of Poitou and Gascony can perhaps be explained by the presence in England at this time of William archbishop of Bordeaux, on 8 May supplied with a ship for his passage home. 17 At the same time, we receive our first certain evidence of the fear, very shortly to be realized, that the barons had attracted the support not only of the King's Welsh enemies but of the King of Scots. On 6 May, Thomas of Erdington was promised repayment of the costs of supplying knights for at least seven castles on the Marches, including Shrewsbury and Clun.18 On the previous day, the King recorded gifts or loans of 30 marks to Robert de Brus, 300 marks to Alan of Galway, and 20 marks to Alan's brother Thomas, earl of Atholl.19 A list of the contents of the Scottish treasury archive in 1282 supplies invaluable proof of the written communications that passed between the barons and the King of Scots. It notes, for example, a 'confederatio' made between the English barons and the King of Scots, letters of the barons of England to the barons of Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmoreland (apparently demanding the surrender of these counties), letters of the mayor and burgesses of London, and letters of Robert de Ros and Eustace de Vescy. In no case, however, are these entries supplied with any firm evidence as to date.20 The best that can be said is that, by the time the barons came to meet with John at Runnymede, in early June 1215, the grievances of both the Scots and the Welsh had clearly already imposed themselves on the agenda for negotiation. Meanwhile, if the barons were now dealing with allies beyond the realm of England, then so too was the King. From Reading, on 6 May, the King issued safe conducts for William de Franchesnet coming to his service from overseas with his 'people' (gens).21 On 8 May, Anfred of Dean was sent to the Cinque Ports with unspecified messages, presumably pleading assistance for the King, and on the same day the mounted serjeants and infantrymen whom Gerard de Gravelines had been sent to recruit, presumably in Flanders, were promised that their wages would be paid from the moment they saw fit to depart for England.22 Although knights from Gascony and Poitou, summoned to England, had been discharged before their sailing, as long ago as 13 March, the King now settled the debts of up to 3100 marks he owed the Templars for this abortive muster, handing over an equivalent sum in gold, presumably from the King's own plate and treasure, with instructions that the Templars could do with this as they saw fit if the King had not redeemed it before January 1216.23 Pressure from the Templars might also explain an order, issued on 5 May, to ensure the prior of Acre, in the Holy Land, the tithes from Berkhamsted and Hemel Hempstead that he been promised when those places were in the custody of the late Geoffrey fitz Peter, earl of Essex.24

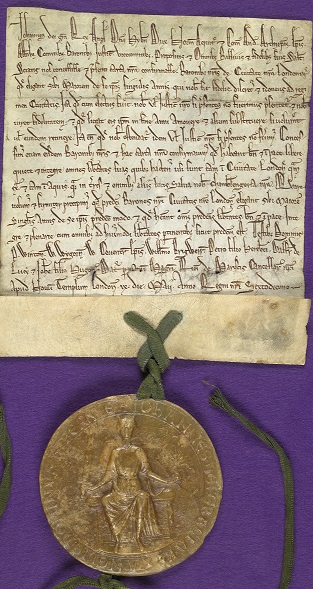

On 5 May, the King had instructed the mayor and sheriffs of London to allow Thomas de Neville the house of a Jew in London, so that Thomas could sit at the Exchequer. Similar instructions were issued to Eustace de Greinville, an Anglo-Norman knight closely associated with Peter des Roches, bishop of Winchester, now addressed as constable of the Tower, presumably acting there as deputy to des Roches, the King's justiciar.25 Four days later, on the eve of his departure from London for Windsor, the King issued the most significant of all the charters granted during this week. For the past twenty years the men of London had been served by a mayor, acting as a 'headman' to adjudicate disputes and to represent the city oligarchy in negotiations with the crown.26 On Saturday 9 May 1215, the barons of the city were granted the right to an annual election of all future mayors, provided only that the successfully elected candidate present himself to the King or the justiciar to swear fealty. At the same time, they were confirmed in 'all their liberties that they have here before made use of'.27 This charter, still perfectly preserved in the London Corporation Archives, marked a significant step along the road to London's self-government. It was issued in a last ditch bid to buy the city's support for the King. Almost exactly a week later, and regardless of the King's attempts at bribery, the Londoners were to open their gates to a rebel army.

1 | The delivery of baronial grievances by a clerk 'who spoke very well to the King' features in the Histoire des Ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 146, but as part of an account of the emergence of baronial resistance that allows for no certain chronology and that may instead refer to exchanges from as early as the autumn of 1214. |

2 | Amongst the various copies of the diffidations of May 1264, see those preserved at Pershore, whence the copy in Flores Historiarum, 3 vols., ed. H.R. Luard (London, 1890), ii, 492-4, with a discussion of their correct date by David Carpenter, The Battles of Lewes and Evesham 1264/5 (Keele, 1987), 19-20. |

3 | RLP, 141. |

4 | RLC, i, 204. |

5 | RC, 206b-7, with a further fragment of the damaged Charter Roll 16 John published in Cal.Chart.R. 1427-1516, 284-5. |

6 | RLP, 135. |

7 | RLC, i, 199. |

8 | RLP, 134b. |

9 | RLP, 135. |

10 | RLP, 135, and cf. RLC, i, 199, for the purchase of 120 pigs by Robert of Kent, the sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk. For the sheriffdom, held until c. 19 April by John fitz Robert, whereafter it was claimed by Roger de Cressy, John's step-brother, acting on behalf of the rebels, see the account in Pipe Roll 17 John, 10, and cf. J.C. Holt, The Northerners: A Study in the Reign of King John, 2nd edn. (Oxford, 1992), 62-3. |

11 | RLC, i, 198b-9. |

12 | RLC, i, 199-9b. |

13 | RLC, i, 199b. |

14 | Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols. (London, 1872-73), ii, 220, with further details supplied by the Histoire des Ducs, ed. Michel, 147-9, suggesting that the siege of Exeter can be dated to c. mid May, after the rebel seizure of London. |

15 | RLC, i, 199. |

16 | RLC, i, 204. For Morgan, a bastard son of Henry II, sent to the Durham monks as the King's envoy on 7 March 1215, his election subsequently refused by the Pope on the grounds of illegitimacy, see RLC, i, 190b; Historiae Dunelmensis Scriptores Tres, ed. J. Raine, Surtees Society ix (1839), 35 |

17 | RLC, i, 199b, and for the concerns of Poitou and Gascony, including the transfer of rents at Niort from a client of Savaric de Mauléon, and the archbishop of Bordeaux's own estate, see RLP, 135; RLC, i, 198b. |

18 | RLC, i, 199. |

19 | RLC, i, 198b. |

20 | Edinburgh, National Archives of Scotland RH5/8/1, whence printed in Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part 2 (London, 1816), 615-17; The Acts of the Parliament of Scotland, ed. T. Thomson and C. Innes, 12 vols. (Edinburgh, 1814-75), i, 107-10; (brief calendar) J. Bain, Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, 4 vols. (1881-), ii, 68-9 no.225. I intend that this be made a Feature of the Month in due course. |

21 | RLP, 135. |

22 | RLP, 135, 141. |

23 | RLP, 135, 141; RLC, i, 198b |

24 | RLC, i, 198b. |

25 | RLC, i, 198b. |

26 | The best account of the emergence of the mayoralty remains that by C.N.L. Brooke and Gillian Keir, London 800-1216: The Shaping of a City (London, 1975), 245-48. |

27 | RC, 207, with an original surviving as London Metropolitan Archives COL/CH/01/10, with near-perfect seal impression in natural wax. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)