John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

1 Mar 1215 |

TNA E 132/1/6 m.3 |

||

2-6 Mar 1215 |

Foedera, 127; RLP, 129-30; RLC, i, 188b-90, 192, 203; Walter of Coventry, ii, 219 |

Hardy, 'Itinerary', places the King at Windsor and then the Tower of London on 1 March. |

|

6 Mar 1215 |

RLP, 130; RLC, i, 190 |

||

6-7 Mar 1215 |

RLP, 130; RLC, i, 190-90b |

||

7-8 Mar 1215 |

Dugdale, Monasticon, v, 573-4; RLC, i, 190b |

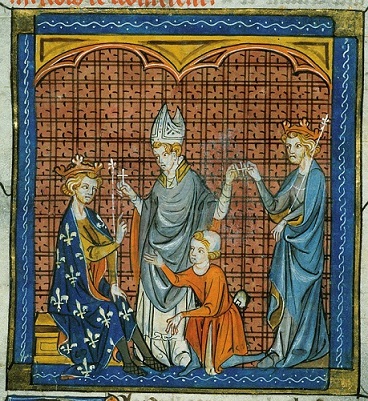

The principal event of this week took place on Wednesday 4 March, in London, when the King took vows as a crusader, administered by William bishop of London (discussed in March’s Feature of the Month). Sewing a white cross onto his outer garment, just as his brother and father had before him, John proclaimed himself not only a English crusader (the French traditionally wore red crosses) but acquired the protections that the Church traditionally extended to all pledged to defend the Holy Land.1 The solemnity of the event was heightened by its timing. It was deliberately staged on Ash Wednesday, the opening of the penitential season of Lent.2 John himself then encouraged others of his court to follow his example: the earls of Chester, Derby, Winchester, and John de Lacy constable of Chester are specifically named as taking the cross on this occasion.3 John de Lacy was rewarded, a day later, with a pardon for all his debts to the crown.4 The Crowland chronicler, followed by Roger of Wendover, reports that John was widely supposed to have acted here, not out of piety, but in order to outwit his political opponents.5 In his dealings with the Pope over the Anglo-French truce of October 1214, the King had already emphasized the needs of the Holy Land.6 From much this time, from October 1214, John can be found amassing a treasure in gold, a standard requirement of any lord hoping to transfer substantial resources to the East. The equipment of a ship, in January 1215, may supply our first certain proof that John was fully committed to the idea of a crusade. Certainly, whatever the sincerity of his vows, his crusader status was henceforth to ensure an added degree of papal protection in his dealings with the English baronage.

Other favours granted this week suggest a similar desire by the King to buy support amongst those whose loyalty remained in doubt, including David earl of Huntingdon, who was promised the third penny of pleas from Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire.7 With his close connections to the Scottish royal court, David was a crucial player in Anglo-Scots affairs. On 3 March, and despite earlier arrangements with the royalist Thomas of Erdington, the Marcher heir William fitz Alan of Clun and Oswestry was allowed to do homage for his father's barony.8 Since 1213, William had been unable to make any payment of the 10,000 mark fine levied against him by the King for his father's lands.9 Wardship of his lands and his marriage had been sold to Thomas of Erdington in 1214 for a further 5000 marks.10 William's appearance in March 1215 is the last sighting we have of him before his death, so that the present arrangements may suggest a deathbed attempt to atone for former royal extortion, perhaps as part of the King's wider settlement with the Lacy family and their kin.11 A day earlier, on 2 March, the King dispatched the bishop of Coventry and three other ambassadors to the Welsh Marches with messages for Llewelyn the Great of Gwynedd, and Gwenwynwyn of Powys, who were assured of the King's ongoing friendship.12 This suggests that fears were already expressed over what was to develop into a baronial alliance with both the Welsh and the Scots.

Although no charters from this week are recorded on the Charter Roll, at least three were issued. On 1 March, at Windsor, the King granted rights within Inglewood forest to the monks of Holm Cultram in Cumberland.13 A few days later, he granted market rights to the Hampshire knight, Aimery de Sacy, and at Ospringe, on 7 March, a general charter of confirmation to the monks of nearby Faversham Abbey.14 The witnesses to these charters, including Peter bishop of Winchester, William Brewer, Henry fitz Count, Philip de Aubigny and Fawkes de Breauté, suggest a court increasingly dominated by the King's friends, many of them aliens, with only limited representation by native bishops or earls.

Evidence of an attempt to appease the mercantile community emerges, with the release of hostages surrendered by the men of Dunwich, previously guarded in London and Angoulême, and with a string of trading licences to particular foreign merchants.15 The debts of the merchants of Ypres to William earl of Salisbury, late commander of the King's expeditionary force to Flanders, remained a preoccupation, as did attempts made by the bishop of Winchester, in the previous year, to arrest chattels belonging to merchants from Denmark.16 Messages were sent to Durham, presumably over the ongoing election dispute in the bishopric, and the King intervened to appeal any attempt by the monks of Glastonbury to persuade papal judges delegate to release them from their subjection to Jocelin bishop of Bath.17 For this latter intervention, several versions of the King's letters were prepared, with the choice as to which to use being left to the royal envoy, Henry de Vere.18 On 5 March, the King presented Robert de Neville to the church of Wigborough in Essex.19 Although at this time only a very minor royal clerk, by 1220 Robert was to emerge as the very first of a long succession of officials named as Chancellors of the Exchequer, distant ancestors to the present chief financial officers of modern English government.20

From London, on Friday 6 March, the King travelled into Kent along Watling Street, via Sutton at Hone, Rochester and Ospringe, making ultimately for Dover, where negotiations had been put in train for the release of his half-brother, William earl of Salisbury, held captive by the French since the battle of Bouvines.

1 | The fullest account is that of the Crowland (alias 'Barnwell') chronicler, in Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols. (Rolls Ser., 1872-73), ii, 109, an account which in turn seems to supply the basis for the paraphrase by Wendover/Paris, in Matthaei Parisiensis , Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard, 7 vols. (Rolls Ser., 1872–83), ii, 584-5. Translations of both accounts are given in March’s Feature of the Month. |

2 | That this was Ash Wednesday is specifically mentioned by the Crowland/Barnwell chronicle, and by the annals of Tewkesbury and Winchester (Annales Monastici, ed. H.R. Luard, 5 vols. (Rolls Series, 1864-69), i, 61, ii, 82). The annals of Canterbury, Oseney/Thomas Wykes refer to it merely as the fourth Nones of March (Annales Monastici, iv, 58; The Historical Works of Gervase of Canterbury, ed. W. Stubbs 2 vols. (Rolls Ser., 1880), ii, 109). Ralph of Coggeshall supplies no date (Radulphi de Coggeshall Chronicon Anglicanum, ed. J. Stevenson (Rolls Ser., 1875), 171). Roger of Wendover, followed by Matthew Paris, misdates the event to 2 February, the feast of the Purification (Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. Luard, ii, 584-5). |

3 | Canterbury annals, in Gervase of Canterbury, ed. Stubbs, ii, 219. |

4 | RLP, 129b. |

5 | Walter of Coventry, ed. Stubbs, ii, 219. |

6 | Selected Letters of Pope Innocent III concerning England (1198-1216), ed. C.R. Cheney and W. H. Semple (London, 1953), 192 no.72. |

7 | RLC, i, 189b. |

8 | RLP, 129b, and cf. Diary and Itinerary 6-12 July 1214. |

9 | PR 16 John, 121; 2 Henry III, 4; 3 Henry III, 6. |

10 | Rot.Ob., 531. |

11 | I. J. Sanders, English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086-1327 (Oxford, 1960), 71, 113y. |

12 | RLC, i, 203 A. Clark and F. Holbrooke, eds., Rymer’s Foedera (new edn., Record Commission, 1818), i, part i, 127. |

13 | A charter noticed in The Register and Records of Holm Cultram, ed. F. Grainger and W.G. Collingwood, Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society vii (1929), 76 nos. 217-18, of which copies survive as TNA E 132/1/6 m.3; C 47/12/8 no.65; BL mss. Harley 3891 fo.18r-v, and Harley 3911 fos.14v-15r, and cf. RLC, i, 189b, |

14 | Sir William Dugdale and Roger Dodsworth, Monasticon Anglicanum, ed. J. Caley, H. Ellis and B. Bandinel, 6 vols in 8 (London, 1846), iv, 573-4 no.4, and for the charter for Aimery de Sacy, known only from a reference in the Close Roll, RLC, i, 189b. |

15 | The men of Dunwich, RLP, 129; RLC, i, 189b, and cf. above 13-19 July 1214. Trading licences, RLP, 130 |

16 | RLC, i, 189b-90. |

17 | Durham, RLC, i, 190b, and cf. RLP, 130. |

18 | RLP, 129b. |

19 | RLP, 129, 129b-30. |

20 | N. Vincent, 'The Origins of the Chancellorship of the Exchequer', English Historical Review, cviii (1993), 105-21, esp. pp.110-14. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)