'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

10 May 1215 |

RLP, 141 |

||

10-12 May 1215 |

RLP, 135-5b |

||

12-13 May 1215 |

RLP, 135b, 141; RLC, i, 199b, 204 |

||

13-14 May 1215 |

RLP, 135b-6; RLC, i, 199b-200 |

||

14-15 May 1215 |

RLP, 136, 141b; RLC, i, 200-200b |

||

15-16 May 1215 |

RLP, 136b, 141b; RLC, i, 200-200b |

This was a week of turmoil and uncertainty. As the King made his way from London as far west as Trowbridge, the barons settled down to the siege of Northampton whilst rebellion stirred in Devon. At Windsor, on the evening of Saturday 9 May, following his departure from London, John issued a charter promising to submit to adjudication by four 'of our barons of England from our side' to be chosen by the King, acting together with four others chosen by 'the barons who are against us'. The Pope was placed above them as arbiter. The intention here was to decide 'all questions and articles that the barons seek from us and propose, and to which we shall respond that we shall stand by the consideration (of the eight) and do that which they consider should be done between us on the aforesaid issues, provided that, before the consideration is made, we are not held to anything in these matters that have been discussed between us and that have been offered by us'.1 This was in effect both to hold out the hand of peace in accordance with the Pope's desire for mediation, and at the same time to withdraw any specific promises that the King might previously have made. The text of the King's charter, with its mixture of perfect and future tenses, is syntactically hesitant. Yet its individual words are carefully chosen. Rather than being addressed to the King's faithful men, it is directed to 'all of Christ's faithful', fidelity to John himself by this time being in short supply. The King places himself not 'under' ('sub') but 'upon' or 'above' ('super') the arbitration of his four representatives, thereby proclaiming that it was he, rather than the barons, the arbiters, or even the Pope, who retained ultimate authority in this process.

On the following day, 10 May, still at Windsor and still seeking compromise, the complaints both of Geoffrey de Mandeville, earl of Essex, over his fine for the marriage of the King's late wife, Isabella of Gloucester, and of Giles bishop of Hereford, over custody of the lands of his late father, William de Braose, were assigned by the King for resolution 'by judgment of our court'.2 At the same time, John issued letters promising 'our barons who are against us' a series of concessions. Pending the outcome of the 'consideration' ('consideratio') to be undertaken by four royalist and four baronial representatives under the supervision of the Pope, the King undertook that he would 'not take or disseise or go against' the barons 'by force or by arms, save by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers in our court'. Securities for these arrangements would be sought from the bishops of London, Worcester, Chester and Rochester and from the royalist, William earl Warenne.3

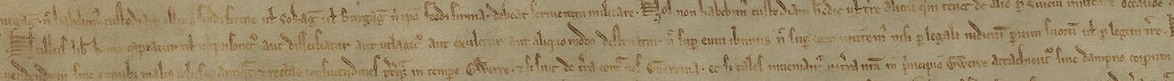

The references to judgments here are particularly notable. A similar reference to judgment by peers or the law of the land was in due course to be reworded for the purposes of clause 39 of Magna Carta ('Nullus liber homo capiatur, vel imprisonetur, aut dissaisiatur, aut utlagetur, aut exuletur, aut aliquo modo destruatur, nec super eum ibimus, nec super eum mittemus, nisi per legale iudicium parium suorum vel per legem terre'). It passed meanwhile through a series of drafts and editorial refinements. Thus, as clause 29 of the Articles of the Barons, sealed early in June 1215, it reoccurs in an undertaking that 'The body of a free man is not to be taken or imprisoned of disseised or outlawed or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will the King go or send against him by force, save by judgment of his peers or by the law of the land' ('Ne corpus liberi hominis capiatur nec imprisonetur nec dissaisietur nec utlagetur nec exuletur nec aliquo modo destruatur, nec rex eat vel mittat super eum vi, nisi per iudicium parium suorum vel per legem terre'). The 'law of our realm' of 10 May has hereby become the more generic, and less personal, 'law of the land'. Even so, our letters of 10 May reveal that the wording of Magna Carta was already beginning to crystalize, more than a month before the meeting at Runnymede. As we shall see, what is perhaps most surprising here is that the concept of judgment by peers or the law of the land/realm came into Magna Carta by a circuitous route that undoubtedly passed via the papal curia in Rome.

These developments should in theory be mappable both against the surviving drafts of Magna Carta, and against Roger of Wendover and the Crowland chronicler's detailed account of negotiations. According to the chroniclers, following their production of Henry I's coronation charter and demand for its renewal in January 1215, the barons met at Stamford and then at Brackley, late in April. According to Wendover, from Brackley and with Archbishop Langton as their go-between, the barons presented the King with a 'schedule' ('schedula') ... setting out the ancient laws and customs of the realm'. The individual 'chapters' ('capitula') of this were composed in part from the coronation charter of Henry I, in part from the 'laws of King Edward (the Confessor)'. The King, having heard these chapters, categorically rejected them.

On the basis of these accounts, it has been suggested that the text of Magna Carta was already more or less complete by late April 1215, with the meeting at Brackley producing a document similar or identical to that eventually sealed by the King at Runnymede.4 This is clearly an exaggeration. Alternatively, the 'Unknown' Charter, preserved in the French national archives, with its balancing off of the coronation charter of Henry I against a series of eleven or so clauses of 'consequentia' that the King was prepared to accept, might conceivably fit the circumstances of mid May 1215. With its specific statement that 'the King has conceded' various things, it can hardly come from the Brackley meeting, whose 'chapters' the King is said categorically to have refused. It has been assigned by one recent commentator to c.10 May, and to the 'consideratio' of disputes to which the King's letters of that date refer, brokered by four royalist and four baronial representatives with the Pope as arbiter.5 This is unlikely. The fact that the 'Unknown' Charter makes no reference to any promise to permit judgment by peers or the law of the land, the key innovation of King John's letters of 10 May, surely makes it hazardous to associate the 'Unknown' charter with the discussions of 9-10 May.6 It seems instead to come from a rather later stage of negotiations.

Meanwhile, the very fact that the King promised to secure a 'consideratio' under papal arbitration reveals that by 9-10 May, the King and almost certainly the barons had at last received the letters from the Pope issued on 19 March, two of which were copied onto the dorse of the Patent Roll. The Pope himself, in July and again in August 1215, reported that his letters of 19 March had arrived in England after the baronial diffidation of the King (3-5 May). At least three papal letters had been issued on 19 March, one to the barons, another to Langton and the English bishops, and a third to the King. Only the baronial and episcopal letters were copied onto the Patent Roll, on the dorse of a membrane that otherwise deals with business after 17 May.7 The contents of the third letter, to King John, have to be inferred from references to them contained both within the other two letters, and subsequently, in reports of them set out in papal letters of July and August 1215.8 What these reports specifically state is that the King was asked to supply the barons with safe conducts, so that baronial disputes might be settled in his court 'by their peers in accordance with the laws and customs of the realm'.

It is precisely such securities, and such a reference to judgment by peers and the laws and customs of the realm, that we find written into the King's letters of 10 May. In other words, judgment by peers or the law of the realm may have been an idea first expressed to the King in the Pope's lost letters of 19 March. Before being carried away here, we should remember that the Pope's phrasing itself very likely originated in England rather than in Rome. The papal chancery was a responsive operation, redrafting appeals from its many petitioners into the routine language of the curia. It could well be that a suggestion that the King allow judgment by peers or the law of the realm had been contained in one or other of the baronial petitions delivered to Innocent III before 19 March, thereafter transferred more or less word for word to the Pope's letters of admonition to the King. Be that as it may, as the King himself subsequently reported to the Pope, the papal instructions had been fully implemented. According to the King, it was the barons themselves who refused all attempts at mediation up to and including the King's offer (of 10 May) of justice 'in all their petitions by consideration of their peers' ('per considerationem parium suorum').9

On 12 May, within two days of the offer of arbitration, throwing off the promises made on 9-10 May, the King wrote from Wallingford to all of his sheriffs commanding the seizure, county by county, of the lands 'of our enemies' ('terras inimicorum nostrorum').10 What provoked this reversal of policy? We must either assume here that the King was acting on 12 May duplicitously, in direct contradiction of the securities that he had promised on 10 May, or that in the meantime the balance had swung from compromise to confrontation, most likely through a baronial rejection of the terms proposed on 10 May. If the barons by this time had read the papal letters of 19 March, then this might explain their refusal of all terms from either King of Pope. The Pope's letters were unequivocal in their demand that the barons return to obedience and give up all attempt at compulsion against the King. Their petitions in future should be made respectfully, in the hope that humility would win for them what violence could never achieve.11 According to the King's letters of 29 May, the barons refused the King's offer of judgment by peers, just as they refused all his other efforts to restore peace.12

Two days after the orders for the seizure of rebel lands, on Thursday 14 May, by which time the King had reached Trowbridge, we begin to receive our first information on specific seizures. The lands of Robert fitz Walter in Cornwall and of Robert de Vere in Devon were granted respectively to Henry the King's bastard son, and to Reginald de Vautorte. Fees of the honour of Trowbridge, forcibly recovered from the lordship of Henry de Bohun earl of Hereford, were conferred upon William earl of Salisbury, the King's half-brother.13 Henry fitz Count, the King's cousin, was to have the fees previously held from him in Devon by William de Mandeville. Another of William de Mandeville's properties was to pass to Ralph de Raleigh, and John de Harcourt was promised a Hampshire manor previously held by William of Huntingfield.14 The land of Henry of Braybrooke was to be seized by the alien, Geoffrey de Martigny, constable of Northampton, and Henry's houses and property were to be laid waste.15

Taken together with the grievances referred to on 10 May, these orders supply our first proper list of the barons, known as early as 14 May to be in open rebellion against the King: Geoffrey de Mandeville earl of Essex, William his brother, Henry de Bohun earl of Hereford, Robert de Vere earl of Oxford, Giles de Braose bishop of Hereford, Robert fitz Walter, William of Huntingfield, and Henry of Braybrooke. Five of these men were later amongst the twenty-five barons of Magna Carta: the earls of Essex, Hereford and Oxford, Robert fitz Walter, and William of Huntingfield. None of them, it should be noticed, was a 'Northerner' in the true sense of the term.

There are hints, even here, that these seizures were still provisional and undertaken only with caution and unease. The honour of Trowbridge had long been disputed between the earls of Hereford and Salisbury, so that Salisbury's success here could be interpreted as an act of royal justice rather than of vengeance.16 Reginald de Vautorte was a ward of Peter des Roches, bishop of Winchester, and perhaps himself still under age.17 The defenceless were thus to be rewarded from the estates of the disobedient.

On 15 May, having heard that the bailiffs of Hubert de Burgh in Norfolk were in a position to seize the wife and son of the rebel sheriff of Norfolk, Roger de Cressy 'our enemy' ('inimicus noster'), the King authorized the seizure of the son, but not of Roger's wife whose sex, apparently, ensured her more chivalrous treatment.18 Meanwhile, on Wednesday 13 May, writing from Marlborough, and apparently still acting in accordance with the truce agreed on 10 May, the King demanded the release of William de Montacute, a rebel baron taken captive by Peter de Maulay, constable of Corfe, to be released under pledges from William's friends.19 Even on 15 May, when the King assigned the lands of the bishop of Hereford to Henry fitz Count, his orders were confined to that part of the bishop's estate 'pertaining to our crown' ('que pertinet ad regale nostrum'), a form of words that suggests a continuing imperative to excuse actions that even the King considered extreme.

Meanwhile, having rejected all royal efforts at peacemaking, the barons remained outside Northampton Castle, unable to press home their siege for lack of machinery. This did not prevent them from obtaining the assistance of various of the townsmen, who attacked and killed members of the royalist garrison deputed to the custody of the vill. In revenge, Geoffrey de Martigny, the constable, burned a large part of the town.20 Fearing that rebellion might spread, the King sent William de Harcourt to the nearby castles of Rockingham and Sauvey, en route for Nottingham.21 Fawkes de Breauté was likewise sent into the Midlands, and William earl of Salisbury to strengthen the garrisoning of London.22 Measures were taken for the defence of Wallingford where, on 12 May, the King issued safe conducts for yet another Flemish mercenary, Henry de Balliol, to come into England on the royal payroll.23 At Corfe, Peter de Maulay was joined by the Templar knight, Alan Martel, and commanded to send fifty horn crossbows to Marlborough, with as many crossbow bolts as they could spare.24 The King's own siege engines were put in a state of readiness, with cords and carriages prepared in Southampton, and a mangonel and a petrary sent from Gloucester to Corfe.25 Armour and eleven more crossbows were delivered to Marlborough from the King's arsenal at Bristol, from which wine and further supplies were sent to Marlborough, Devizes, and to Launceston in Cornwall.26 Twelve of the leading citizens of Bristol were summoned to meet with the King at Marlborough on 17 May, in order that he could explain his business to them, and so that they might deliver wine.27 At Bristol itself, the castellan, Peter de Chanceaux, was told to go with four trustworthy men to the King's treasury, where the locks were to be broken and replaced. Having taken out part of the treasure, 500 marks of which were commanded for Engelard de Cigogné at Gloucester, Peter was to have the new keys carefully kept, sealed up by the four men who had witnessed his withdrawal.28

Winchester Castle was released to Savaric de Mauléon and his Poitevins.29 The Queen, together with Henry, the King's eight year-old son and heir, was brought under custody of knights of the bishop of Winchester, from Winchester to Marlborough.30 The Breton courtier, Philip d'Aubigny, was sent into Shropshire to assist with the defence of Bridgnorth, itself now committed to the keeping of Robert de Courtenay and Walter de Verdun.31 In the far west, the county of Devon was committed to Henry de la Pommeraye and John of Earley, a close associate of William Marshal, the joint appointment to a single sheriffdom revealing the depth of the King's anxiety that rebellion had now spread to the west. Eudo de Beauchamp was ordered to surrender the castle at Exeter to the new sheriffs, and the knights of the county were summoned to attend the King at Marlborough.32 According to the Crowland chronicler, these orders came too late to prevent an attack upon Exeter, whereafter the rebels dispersed 'into the moors', presumably to Dartmoor and beyond.33 The anonymous of Béthune describes the seizure of Exeter by the 'Northerners' ('Li Norois'), the King's orders to William earl of Salisbury and his Flemish mercenaries to proceed to Sherborne and from there to Exeter, the earl's decision to seek out the King (who he found at Winchester, presumably around 19-20 May), and the subsequent flight of the rebels from Exeter, faced with an assault by Robert of Béthune.34

It is a striking fact that, despite what the chroniclers and papal letters suggest was his central role in negotiations between King and rebels, Stephen Langton makes virtually no appearance in royal letters after mid-March 1215.35 In the present week, we receive our first hint of what was shortly to develop into a major rift between Langton and the King, following the promotion of the archbishop's brother, Master Simon Langton, to the vacant see of York. This was first explicitly forbidden by the King in June 1215, and definitively quashed by the Pope that August.36 However, the dispatch to Rome on 13 May of an embassy headed by two canons of York, Master Walter of Wisbech and Master William of Cave, and a letter to the York chapter appealing against any attempt to elect an archbishop 'suspect' to the King, surely suggest that, as early 13 May, Master Simon's name had already entered the lists.37

After a week of frantic preparations and failed peace initiatives, it is still clear that the King remained hopeful that the storm would pass, and his authority be restored. Why else would he have written, as he wrote to Geoffrey de Martigny, castellan of Northampton, and other Midland constables, on 16 May, commanding that they observe a truce that Archbishop Langton was expected to make with the barons, set to last to 21 May or even longer?38 The barons, having abandoned the siege of Northampton, were perhaps viewed by the King as a busted flush. How misguided this view was we shall learn next week.

1 | RC, 209b, whence J.C. Holt, Magna Carta, 2nd edn. (Cambridge, 1992), 492 no.3, and the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, no.4. |

2 | RLP, 141, and , and the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, no.6. |

3 | RLP, 141, whence Holt, Magna Carta, 492-3 no.4, , and the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, no.5. |

4 | Such is the claim of the Wikipedia entry, accessed 8.v.15, for 'Brackley', clearly a product of local enthusiasm. |

5 | RLP, 141. The 'Unknown' Charter is unequivocably assigned to 10 May by David Starkey, Magna Carta: The True Story Behind the Charter (London, 2015), 40-2. Like much else in Starkey's account, speculation is here repackaged as certain fact. |

6 | For detailed but in the end inconclusive discussion of the date of the 'Unknown' Charter, see Holt, Magna Carta, 420-3 |

7 | See the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, nos 1-2. |

8 | See the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, no.3. |

9 | Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae et Acta Publica, ed. T. Rymer, new edn., vol. I, part i, ed. A. Clark and F. Holbrooke (Record Comm., 1816), 129, letters of 29 May 1215, with text and translation in the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, no.7. |

10 | RLC, i, 204. |

11 | See the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, no.1. |

12 | See the forthcoming Feature of the Month for May, no.7. |

13 | RLC, i, 200. For Henry the bastard son of King John, see C. Given-Wilson and A. Curteis, The Royal Bastards of Medieval England (London, 1984), 47, 130; RLC, i, 161. |

14 | RLC, i, 200. |

15 | RLC, i, 200, including a grant of Henry's lands at Horsenden (Buckinghamshire) to Philip of Perry. |

16 | I.J. Sanders, English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086-1327 (Oxford, 1960), 91-2; Holt, Magna Carta, 206-7. |

17 | N. C. Vincent, Peter des Roches: An alien in English politics, 1205-1238 (Cambridge, 1996), 72-3, 130n., and for his coming of age, dated to 1217, see Sanders, English Baronies, 91. |

18 | RLP, 141. |

19 | RLP, 135b. |

20 | Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols. (London, 1872-73), ii, 220-1. |

21 | RLP, 135b. |

22 | RLP, 135b, 136b. |

23 | RLP, 135b; RLC, i, 199b. |

24 | RLP, 135b-6. |

25 | RLC, i, 200b. |

26 | RLP, 136; RLC, i, 199b. |

27 | RLC, i, 200. |

28 | RLP, 136b, also in RLC, i, 200b, and for the money commanded for Engelard five days earlier, RLP, 135. |

29 | RLP, 135, 136b, and at the same time Savaric was granted custody of the Dorset manors of Wareham and Cranbourne: RLP, 136. |

30 | RLP, 136, and for the Queen supplied with firewood at Winchester, RLC, i, 199b. |

31 | RLP, 136b. Robert was rewarded with custody of the Buckinghamshire manor of Waddesdon, to which his family had a hereditary claim (VCH Buckinghamshire, iv, 108-9), and cf. the grant of the land of Joscy de Bayeux in Somerset to Henry de Courtenay, RLC, i, 200-200b. Ingelram de Préaux and his men were also to be received at Bridgnorth: RLC, i, 200. |

32 | RLP, 135b-6; RLC, i, 199b-200. |

33 | Walter of Coventry, ed. Stubbs, ii, 220, 'occupata Exonia primum, postea in nemoribus se occuluerunt'. |

34 | Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 147-9. |

35 | See King John’s Diary and Itinerary for the weeks of 15-21 February and 22-28 February, 15-21 March, and 12-18 April. |

36 | RC, 207b; The Letters of Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) concerning England and Wales: a calendar with an appendix of texts, ed. C. R. Cheney and M. G. Cheney (Oxford, 1967), no.1017. |

37 | RLP, 141 (where in the letter to York for 'vobis sit suspectus' read 'nobis sit suspectus'), and for Walter and William as canons of York, see J. Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300, ed. D. E. Greenway (London, 1999), vi (York). |

38 | RLP, 136b, sent to Geoffrey de Martigny and also to John of Bassingbourne, Fawkes de Breauté, Hugh de Boves and Hugh de Balliol. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)