Baronial grievances aired at the New Temple

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

11 January 1215 - 17 January 1215

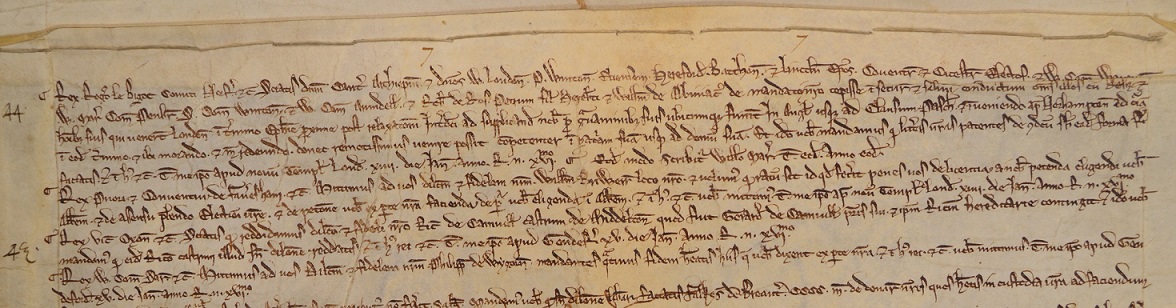

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

7-12, 14-15 Jan 1215 |

RC, 202b-3b, 204b, 205b; RLP, 126-7; RLC, i, 182b-3 |

||

14-19, 21 Jan 1215 |

RC, 203-3b, 204b-5; RLP, 126b-7b, 128; RLC, i, 183-4b, 187 |

The present week witnessed the final sessions of the council convened at the New Temple, followed by the King's departure for Guildford and ultimately for Winchester and Southampton. The discrepancy between the King's presence both in London and in Guildford on 14-15 January is presumably the result either of the misdating of writs on the chancery rolls, or of the simultaneous issue of letters by the King at Guildford, using a privy seal, and the chancellor with the great seal still at London. We have found the King, from 7 January onwards, established in council with his barons. It was as a result of this meeting that we receive our first clear proof that baronial discontent had begun to spill over into open resistance to the King. Letters recorded on the Patent Roll on Wednesday 14 January, at the close of the New Temple conference, represent our first ‘official’ notice that baronial grievances were being publicly aired. To the malcontents, on 14 January, the King granted letters of safe conduct, guaranteeing their safety until the close of Easter (26 April) when they would come to court at Northampton, the safe conducts to last until such time as the most distant of these men could return from Northampton to their proper homes.1 There are number of points of interest here. First and foremost, the safe conducts themselves were issued by the King acting in concert with a group of eight bishops, two bishops elect, four earls and three barons, seventeen men in all, headed by Stephen Langton as archbishop of Canterbury, said to have added their authority to the King’s safe conduct acting at the King’s command (de mandato nostro).

The names supplied here are themselves significant. William Marshal seems to have remained staunchly loyal to the King, as did others of the guarantors, including Peter des Roches bishop of Winchester, the earl Warenne and William earl of Arundel. Most of the guarantors however, were either neutral, such as the previously exiled archbishop, the bishops of London, Ely, Bath and Lincoln and the bishop-elect of Chichester (Richard Poer), or in due course were to be numbered amongst the leading rebels against the King: Giles bishop of Hereford, Roger Bigod earl of Norfolk, Saher earl of Winchester, Robert de Ros and William de Aubigny of Belvoir. In other words, by 14 January 1215 either there was no clear appreciation on the King’s behalf of the depth of baronial discontent, or the conspiracy of various of his leading courtiers, including the earls of Norfolk and Winchester, had already come into the open. This second possibility is perhaps the more likely, not least because our knowledge of the safe conducts granted to the malcontents comes from the King's letters to Roger Bigod and William Marshal, a paired malcontent and royalist, asking them to issue their own letters in accordance with the agreements made in London.

At this time, nonetheless, it may still have been supposed that the majority of the malcontents were, as the chroniclers subsequently proclaimed them, ‘Northerners’, from the furthest northern counties. Such an understanding might explain why the King’s letters lay such emphasis upon the ability of those dwelling at great distances from Northampton to return to their homes before the expiration of any truce. The term ‘Northerner’ to describe the malcontents is first recorded at about this time, in the records of the King’s law courts at Westminster. Here we find the Norfolk landowner, Roger de Cressy, unable to attend to warrant at Westminster ‘because Roger is one of those Northerners (unus ex Norensibus) who have the King’s peace until the close of Easter (26 April)’2

Quite what grievances were raised in the council of early January? Here we can turn first to the chroniclers. We have already found Roger of Wendover reporting the first stirrings of communal resistance amongst the barons, said to have emerged in the autumn of 1214 and then to have been postponed for further action 'after Christmas'. The vernacular French chronicle, known as the Histoire des ducs de Normandie, supplies only a vague chronology of events between October 1214 and April 1215, but nonetheless speaks of a 'parlement' at which the principal malcontents demanded that the King respect the liberties granted in the coronation charters of Henry I and King Stephen. The list of rebels supplied in the Histoire was drawn up in hindsight, so that we cannot be certain that all were already in public opposition as early as January 1215. Nonetheless, the Histoire names Robert fitz Walter, Saher de Quincy earl of Winchester, Gilbert de Clare (son of Richard earl of Hertford), Geoffrey de Mandeville earl of Essex, and then a group specifically set apart as 'Northerners' (Norois) 'because their lands lay towards the north': Robert de Ros, Eustace de Vescy, Richard de Percy, William de Mowbray ('as small as a dwarf, but large in valour'), and a man named here as Roger de 'Mongobori', presumably Roger de Montbegon.3

The writer whose work goes under the name of ‘Walter of Coventry’, subsequently identified as a ‘Barnwell’ chronicler, more recently reassigned to Crowland Abbey in Lincolnshire, supplies a detailed account of what was supposed to have taken place in early January.4 Having described the emergence of a group of ‘Northerners’ (Aquilonares), who in the previous year had refused either to pay scutage or to attend the King in Poitou, and having listed their demand, that the King uphold the terms of the coronation charter of Henry I, the chronicler reports their meeting the King at London 'around Epiphany' (6 January). Joined by several of the bishops, they were frustrated by the King who sought delays, fixing 26 April (a date confirmed elsewhere in our sources) as the occasion for a final response, the malcontents being offered letters of safe conduct in the meantime. From this time, the chronicler alleges, the coronation charter of Henry I became the subject of public debate (vulgata est). Alluding to Ezechial 13:5 and possibly to Ailred of Rievaulx's commentary on Isaiah 13:4-8, the chronicler emphasizes the unanimity that now bound the opposition party, here citing passages from scripture that, in the past, had been applied with particular force to the unanimity expected of crusaders. To this, the King responded with demands for 'something that had many times before been done, namely that fealty be sworn throughout England to stand with the King against all men, but with this further uncustomary clause added, "to stand against the aforesaid charter"'. This, the barons refused so strongly that the King backed down. The King nonetheless wrote to the Pope to complain that he was the target of a rebellion. He already knew, from informants amongst the conspirators, that this had been 'for a long time planned'. The barons, for their part, now appealed to the Pope against the King's unjust tyranny.5

Thus far, we have evidence for the public debate of the coronation charter of Henry I, and that the King responded with demands for a general oath of fealty from the barons, consistent with oaths that he had previously extracted, most notably in 1209, when he had demanded that virtually the entire adult male population swear fealty to himself and his new-born son. In January 1215, further discussions were postponed to late April. In the meantime, appeals were made to the Pope, both by the King and the barons.6 We might be inclined to dismiss the further claim of the Crowland chronicler, that the King had demanded specific oaths from the barons 'against the charter' of Henry I, were it not for corroboration, at the Roman end of the story, from a letter sent back to England by the King's clerk, Walter Mauclerk. Mauclerk reports his arrival at Rome on 17 February, after delays caused by illness. Since the journey from England to Rome generally took three weeks or more, even at the fastest rate of travel, we must assume that he had set out by the second week in January, perhaps even earlier than this.7 Mauclerk reports the arrival in Rome, on 8 March, of John of Ferriby, clerk of Eustace de Vescy, and Osbert (of Seamer), chaplain of Richard de Percy. Both of these clerks were later to earn notoriety and excommunication for the part that were to play in the baronial diffidation of King John in May 1215.8 According to rumours that had reached Mauclerk from within the curia, these agents came on behalf of 'nearly all of the barons of England', including (but only as one subset) 'the northerners' (boreales). Their intention was to petition the Pope to uphold 'the ancient liberties' of the English barons as confirmed by charters granted by King John's ancestors and by John's own oath'. In Rome, the baronial envoys apparently complained that during their Epiphany meeting of early January 1215, the King had shown contempt for his obligations (perhaps here referring to the King's coronation oath), not least in demanding that the barons make promises and grant charters repudiating any future attempt to demand their ancient liberties (i.e. the coronation charter of Henry I). This demand by the King, Mauclerk reports, had been rejected by all save three courtiers: Peter des Roches, bishop of Winchester, the earl of Chester, and William Brewer. According to the rumours reported by Mauclerk, the baronial agents now insinuated to the Pope that whatever King John might have done to uphold the liberties of the Church (presumably via the charter of free elections issued in November 1214, reissued in January 1215) or to grant rents to the church of Rome (through his surrender of the realm as a papal fief) had been forced upon him under compulsion from the barons, the Pope's most loyal and valiant defenders.9

What is chiefly significant here is the confirmation that these letters supply of the Barnwell/Crowland chronicler's report of complaints raised by the barons, not only that the King had refused, at their January meeting, to confirm the liberties and ancient charters demanded by 'the northerners', but that John in turn had demanded letters and oaths from his critics repudiating all future attempts to secure such liberties. Mauclerk's letters are also significant for supplying the names of at least two of the baronial leaders already in opposition to the crown. Both of them were 'northerners' in the sense that they owned extensive northern property, albeit in association with land further south: Eustace de Vescy and Richard de Percy. The Pope's response, still pending when Mauclerk's letter was sent, came on 19 March in papal letters addressed 'to his beloved sons the magnates and barons of England', lamenting the differences that had arisen between barons and King, but utterly condemning those who 'dared form leagues or conspiracies against (the King) and presumed arrogantly and disloyally by force of arms to make claims which, if necessary, you should have made in humility and loyal devotion'. The Pope hereby denounced all 'leagues and conspiracies' (conspiraciones et coniuraciones) that had arisen since the beginning of the Interdict in 1208, demanding loyalty from the barons who should render their customary services to the King. To the King, the Pope wrote urging moderation and kindness, reminding him of the need for remission of his sins, and suggesting that reform might lead not only to peace but to greater devotion between King and subjects.10 On the same day, he wrote to Langton, rebuking him for his failure to mediate the disputes that had arisen, noting rumours that Langton himself favoured the opposition, and commanding him to excommunicate all conspirators.11 Ten days later, apparently in response to the arrival of further envoys from the King bearing a copy of the charter of free elections as issued at the New Temple on 15 January, the Pope issued formal confirmation of the King's charter, recited in full after a long and flowery preamble, full of scriptural references in praise of God's majesty and the virtues of peace.12 On 1 April, again in response to representations by King John, the Pope wrote to the magnates, barons and knights of England complaining of their failure to pay the scutage (scutagium) demanded since 1214 for the army of Poitou.13 As this suggests, not only had non-payment of scutage been the first warning sign of baronial discontent, but into 1215 it remained a bone of contention, cited by the King as proof of baronial disloyalty. The King's complaints here may have pursued a particular legal point, designed specifically to counter the charges laid against John by his barons. The papal letters of 1 April demand payment of scutage not least on the grounds that, 'without judgement' (absque iudicio), nobody should be deprived of right. Especially not the King who was himself prepared 'to show justice to petitioners' (postulantibus iustitiam exibere). Here, and not for the first time, we find the King and his councillors neatly deflecting baronial arguments, echoing charges made against the King by reversing them back against his critics. In this particular instance, it was the barons, not the King, who were accused of acting 'without judgement' (absque iudicio), even though it was the King's denial of justice (iudicium) that was one of the principal charges leveled against him, subsequently finding a prominent place in clauses 39 and 40 of Magna Carta.

As to who else might already have come out into the open as a critic of John's government, we have seen already that the charters to churchmen reissued in January 1215 after their initial award in November were reissued with their witness lists unchanged. In other words, the witness lists to several royal charters of January 1215 cannot be relied upon as evidence for who, by this stage, was or was not still considered persona grata at court. Much more reliable as a list of those at court is a charter, copied onto the chancery Charter Roll only in an abbreviated form, but surviving in duplicate originals in the Derbyshire Record Office. Issued on 11 January, this confirms the liberties of the monks of Chester in Derbyshire, and is witnessed exclusively by courtiers (Peter des Roches, William Brewer, William de Cantiloupe, Richard Marsh) or by loyalist earls (Chester, Warenne, Arundel, Ferrers).14 Several of these men appear again in charters issued later that month, both in London and at Guildford, alongside others, however, whose allegiance was later to waver, including William de Aubigny of Belvoir, Richard de Canville, Simon of Kyme, and Henry fitz Count.15 This perhaps suggests a deliberate display of moderation on the King's behalf, and a desire at least to be seen to be dealing equitably with his critics.

Some courtiers were offered special favours during this period. Thus the earl Warenne and the earl of Arundel were both granted houses in the London Jewry.16 William Marshal, earl of Pembroke, received custody of the vacant Pembrokeshire bishopric of St David's.17 William Brewer's newly founded hospital at Bridgewater in Somerset was granted a royal confirmation charter.18 Thomas of Erdington received the honour of Montgomery pending rival claims to be answered in the King's court.19 The Templars, who had hosted the January council, received £10 of land in Buckinghamshire and a house in Northampton formerly belonging to the Jewish money lender, Aaron of Lincoln.20 All of these grants were by way of rewards for loyalists rather than attempts to buy back the allegiance of malcontents.

As for the opposition, besides Eustace de Vescy and Richard de Percy both named in the letters of Walter Mauclerk, we have already noted the position of Roger de Cressy, described as a 'northerner' in the rolls of the King's court in January or February 1215. Others named in the letters of safe conduct authorized on 14 January may already have come into the open as critics of the King: Roger Bigod, Saher de Quincy, Robert de Ros, and William de Aubigny. Two grants made on 15 January suggest attempts to buy back wavering support. Thus Robert de Ros received the Cumberland manors of Castle Sowerby, Carlton (in Penrith) and Upperby (in Carlisle), pending the restoration of the lands that, since 1204, he had been obliged to forfeit in Normandy. Ros was at this time himself sheriff of Carlisle. He was also promised the manor of 'Audeworth' (unidentified) in Yorkshire at its ancient farm, and as the King's 'faithful friend' received licence to take six deer from the northern forests.21 On the same day, the castle of Middleton Stoney in Oxfordshire was restored to Richard de Canville as his by right of his father, Gerard de Canville, a long-time supporter of King John from John's days as count of Mortain, before 1199.22 The mother of Geoffrey de Mandeville, Avelina widow of Geoffrey fitz Peter, was restored to an Essex wardship of which she claimed to have been deprived.23 There was also a settlement intended to regulate the family inheritance of Henry fitz Ailwin, late mayor of London.24

We have already found the King reissuing the charter of free elections for the English church and in general acting cautiously in his approaches to Langton and the bishops. In the present week, there were orders for the release of various of Langton's tenants wrongfully arrested for poaching.25 Throughout January, the former exiles William bishop of London and Jocelin bishop of Bath are named in regular attendance at court.26 Even so, there are signs here that the King continued, in practice, to do his best to wriggle out from the more onerous of the measures to which the charter of free elections had committed him. To Faversham Abbey in Kent he sent William Brewer to preside over a 'free' election.27 At Battle Abbey in Sussex, his interventions were even more direct. The charter of free elections implied (albeit without explicit provision) that elections should henceforth be held in situ, in monastic or cathedral chapter houses, rather than before the King in his own chapel. On 17 January, the King nonetheless asked the monks of Battle to send representatives to court in order to elect a new abbot, the pretext here being that the King wished to become better acquainted with the monastic community.28 A similar summons to court had already been issued to the canons of St David's Cathedral in Wales, recently placed under the custody of William Marshal.29 On 16 January, the King wrote (in distinctively ecclesiastical Latin) to Giles de Braose bishop of Hereford, asking that he assist efforts to secure the election of Hugh Foliot, archdeacon of Shropshire, as St David's new bishop, an effort that in due course was to be frustrated by local insistence upon a native Welsh bishop.30

Other business this week concerned ongoing arrangements for the ransoming of prisoners taken in 1214. From Guildford, on 15 January, the King wrote to his half-brother, William earl of Salisbury, informing him of the dispatch of Philip of Worcester as a trustworthy envoy.31 William had been a prisoner of the French since the battle of Bouvines in July 1214. The intention was now that he be exchanged for Robert of Dreux, the most significant of the French prisoners taken by John during his expedition to the Loire. To this end, Robert was to be removed from custody at Gloucester and brought under close guard to Winchester.32 Fawkes de Bréauté, the King's Norman mercenary captain sent to supervise these arrangements, was to receive money from the King's treasure at Marlborough in order to pay the wages of other mercenary serjeants.33 As this suggests, John's encounter with the discontented barons had reinforced the urgent need for preparations to meet rebellion should it arise. Thus, in the present week, there were orders for the purchase of crossbows, and for the munitioning of Colchester castle, itself an indication that trouble was anticipated from East Anglia, not just from the far north, and that it was the northern approaches to London that were most closely watched.34

On a less contentious note, at some time during the conference at the New Temple, a man named William Gruel fined 100 marks to have the land and office of Laurence, hereditary user of the King's Exchequer together with the wardship of Laurence's heir and widow.35 From some years before this, we possess an impression of Laurence's seal, one of several such seals surviving for minor court officials. Laurence's seal shows a standing figure clutching a round object, perhaps either David with the head of Goliath, or Perseus with the head of Medusa.36 As I have argued elsewhere, such seals are an important source of evidence for our knowledge of humour at court, in this instance suggesting an official's obligations to grapple with the 'giants' seeking access to the King's Exchequer, or perhaps more plausibly, to cut through the serpentine coils of bureaucracy that surrounded the King.37

1 | RLP, 126b, with full translation as a Feature of the Month. Note that there is an uncustomary error of transcription in the printed version in RLP, corrected in the Feature. |

2 | Curia Regis Rolls, vii, 315, an undated entry from a fragment of the court roll for the Hilary term, whose first datable entry (p.312) clearly predates 2 March 1215. |

3 | Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 145-6. |

4 | For the recent reattribution to Crowland, thanks to work by Christian Ispir, see D. Carpenter, Magna Carta (London, 2015), 86-7. |

5 | Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols. (London, 1872-73), ii, 217-18, with full translation as a Feature of the Month. |

6 | For the events of 1209, J. R. Maddicott, 'The Oath of Marlborough, 1209: Fear, Government and Popular Allegiance in the Reign of King John', English Historical Review, cxxvi (2011), 281-318. |

7 | For trans-Alpine communications at this period, see Y. Renouard, Etudes d'histoire médiévale, 2 vols. (Paris, 1968), ii, 677-718. For specific timings from England, see P. Chaplais, English Diplomatic Practice in the Middle Ages (London, 2003). |

8 | See the letters of the papal commissioners, September 1215, in English Episcopal Acta IX: Winchester 1205-1238, ed, N. Vincent (Oxford, 1994), 82-6 no.100. |

9 | Diplomatic Documents, ed. Chaplais, 28-30 no.19, also in Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 120, with full English translation in the Feature of the Month. |

10 | Selected Letters of Pope Innocent III concerning England (1198-1216), ed. C.R. Cheney and W. H. Semple (London, 1953), 194-5 no.74, from the dorse of the Patent Roll (Grave gerimus et molestum, 19 March 1215). |

11 | Ibid., 196-7 no.75, again from the dorse of the Patent Roll (Mirari cogimur et moveri, 19 March 1215). |

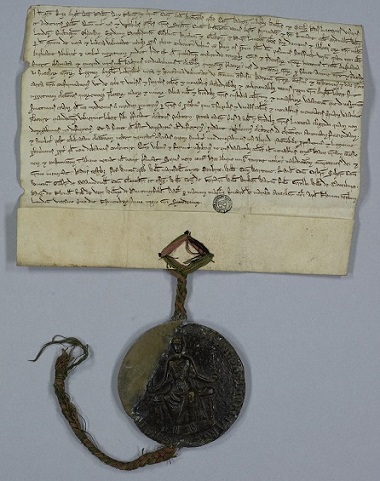

12 | Ibid., 198-201 no.76, from the original, now TNA SC 7/19/17 (Dignis laudibus attolimus, 30 March 1215). |

13 | Ibid., 202 no.77, from the original, now TNA SC7/19/15 (Significavit nobis carissimus, 1 April 1215). |

14 | Matlock, Debyshire Record Office D779B/T123-4, supplying details missing in the enrolment, RC, 202b-3, 204b. |

15 | RC, 203-3b. |

16 | RC, 203, and for the charter to William earl of Arundel, granted on 22 January, see the original now Truro, Royal Institution of Cornwall, Courtney Library ms. HZ/1/24, not enrolled on the Charter Roll, also granting earl William 84 acres of land at Havering in Essex confiscated from a convicted felon. |

17 | RLP, 126; RLC, i, 182b |

18 | RC, 204b. |

19 | RC, 203b, also from another source, in Oxford, Bodleian Library ms. Dugdale 15 p.267, and cf. RLP, 127; RLC, i, 184, suggesting that the date of the charter, left unspecified on the Charter Roll, should be 18 January. |

20 | RC, 203-3b; RLC, i, 187, and cf. RLC, i, 183b-4. |

21 | RLP, 128; RLC, i, 183, 187, and for Ros in general, see J.C. Holt, The Northerners: A Study in the Reign of King John, 2nd edn. (Oxford, 1992), 24-6. |

22 | RLP, 127. |

23 | RLC, i, 187. |

24 | RLC, i, 187. For other such orders that may reflect grievances dealt with on a piece-meal basis, see the instructions benefitting Hugh Peverel of Sanford (in Cornwall), Hugh de Beauchamp (also in Cornwall), Robert de Vaux (in Suffolk), and Nicholas de Verdun (in Lincolnshire); RLC, i, 182b-4. |

25 | RLC, i, 187. |

26 | RC, 203-3b, 204b, and for orders specifically benefitting bishop Jocelin, see RLC, i, 187. |

27 | RLP, 127, and cf. the assent given to an election held at Keynsham Abbey, RLC, i, 187. |

28 | RLP, 127, 'cum domus vestre persone nob(is) penitus sint ignote'. |

29 | RLC, i, 182b. |

30 | RLC, i, 203; John Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300, ix, The Welsh Cathedrals, ed. M.J. Pearson (London, 2003), 47. Hugh Foliot in due course succeeded the rebellious bishop Giles as bishop of Hereford: Le Neve, Fasti, viii, Hereford, ed. J.S. Barrow, 5-6, 26-7. |

31 | RLP, 127, and for Philip's embassy, see also RLC, i, 183. |

32 | RLP, 126b; RLC, i, 183.. |

33 | RLP, 126b, repeated p.127, and for Fawkes at court, at Guildford on 17 January, see RC, 204b. |

34 | RLC, i, 182b. |

35 | RLC, i, 187, undated but appearing amidst a miscellaneous selection of letters patent and other commands issued at the New Temple, inserted out of place in a later membrane of the Close Roll. |

36 | Cambridge, St John's College Archives D.19.142, a grant of property by Laurentius domini re(gis) de s(c)accar(io) hostiarius, witnessed by William of Ely as King's treasurer et ceteris baronibus de scaccar(io). Small vesica-shaped seal in green wax, a standing figure in left-facing profile, carrying a round object in its right hand and an indeterminate ?weapon in its left, legend: SIGILL' <LA>URENTII FIL' GALFRID<I +>. |

37 | For the proliferation of serpentine imagery at the courts of Henry II and his sons, see N. Vincent, 'The Seals of King Henry II and his Court', Seals and their Context in the Middle Ages, ed. Phillipp R. Schofield (Oxford, 2015). |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)