The Articles of the Barons and Runnymede

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

7 June 1215 - 13 June 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

8 Jun 1215 |

RLP, 142b; RLC, i, 214 |

||

8 Jun 1215 |

RLP, 143 |

||

9 Jun 1215 |

RLC, i, 214-14b |

||

9 Jun 1215 |

Chronicle of the Election of Hugh, 168-9 |

||

10 Jun 1215 |

Chronicle of the Election of Hugh, 170-1 |

||

10-14 Jun 1215 |

RLP, 142b-3; RLC, i, 214b; Chronicle of the Election of Hugh, 170-3 |

Once again, this was a week of momentous negotiations leaving very little written evidence on the chancery rolls. Writing from Odiham on Tuesday 9 June, the King specifically referred to his use of the privy seal in the absence of the great seal, itself presumably in the custody of Richard Marsh who this week, as last, may have been engaged in diplomatic activity away from court.1 Sunday 7 June was the feast of Pentecost. The celebration here opened with Venantius Fortunatus' great hymn 'Salve festa dies'. Once again, the liturgy, with its emphasis upon rebirth, the Lord's destruction of his enemies, and the privileges of discipleship, offered an ironic counterpoint to political events. The King himself had the 'Laudes', the celebration of Christian kingship, sung before him two of the clerks of his chapel.2 This liturgical echo continued throughout the week, with its special prayers and propers for each day through to Trinity Sunday (14 June 1215).3 It was perhaps as one amongst several gifts made at Pentecost that, on Monday 8 June, the King commanded silk robes for Walter de Beauchamp.4

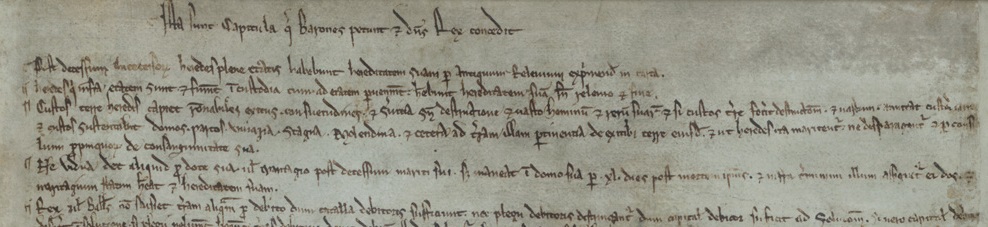

This was the background against which the King prepared to meet his baronial enemies. The King's own movements this week have never been properly traced. Having celebrated Pentecost at Winchester, on Monday 8 June, he headed not to Merton (as both Thomas Duffus Hardy and J.C. Holt supposed), but south to the manor of Merdon, now an outer suburb of Southampton, in the Middle Ages the site of a castle of the bishop of Winchester built in the reign of King Stephen but slighted since 1156.5 This progress into the south then halted. The King instead turned northwards for Odiham and Windsor, reaching Windsor on Wednesday 10 June. The reversal here is perhaps explained by letters issued at Merdon on 8 June, offering safe conducts to all who should come from the baronial side to Staines on Tuesday 9 June or remain there involved in the making of peace until Thursday 11 June.6 J.C. Holt and C.R. Cheney, the two principal modern authorities, agree that this supplies evidence that negotiations were approaching their climax and that both parties were now in a position to issue a statement of intent. Reduced to writing as the 'Articles of the Barons', a single-sheet document setting out the baronial demands that the King had conceded ('Ista sunt capitula que barones petunt et dominus rex concedit'), this can only have been sealed when the King was once more in possession of his great seal. Cheney suggested that the 'Articles' were sealed at Runnymede on 15 June.7 Holt, more plausibly, suggested 10 June, the date of the King's arrival at Windsor, and also the date on which the King dispatched letters prolonging the truce, originally set to expire on Thursday 11 June, through to the Monday afterwards, 15 June.8 It was this date, 15 June, that in due course appeared as the date of Magna Carta: a settlement devised after further discussion and revision of the terms set down in the 'Articles'. David Carpenter has offered convincing arguments to suggest that the 15 June date is to be taken at face value, as the occasion on which Magna Carta itself was first sealed and offered to the barons as the basis for a solid peace.9

In the meantime, on 10 June, the earl of Salisbury and ten others of the King's most trusted commanders were forbidden from attempting any violation of the truce.10 On the following day, 11 June, and as a further sign of his desire for reconciliation, the King commanded the keepers of the vacant abbey of Bury St Edmunds to recognize Hugh of Northwold as abbot.11 Thus, after four years, ended one of the most protracted, and certainly the best documented vacancies in English monastic history. The dispute's chronicler supplies a crucial piece of evidence here with his assertion that, having left Bury on 5 June, Abbot Hugh met with the King and Archbishop Langton at Windsor on Tuesday 9 June. There, Hugh was told to return to meet the King the following morning 'in the meadow between Windsor and Staines'. At this second meeting, on 10 June, the King not only granted Hugh the kiss of peace but invited him to dine that evening at Windsor. If we are to believe the chronicler, the dinner itself was a tempestuous affair, interrupted by a plea for mercy from Hugh's chief enemy, the sacrist of Bury, against whom the King swore a mighty oath 'By God's feet'.12 What is of particular significance, so far as the argument about the date of the 'Articles of the Barons' is concerned, is that the Bury chronicler enables us to place King John in 'the meadow between Staines and Windsor' on 10 June, the day of the prolongation of the truce extended to rebels and in all likelihood the day on which the 'Articles of the Barons' were sealed with the King's great seal. The negotiation of the 'Articles', indeed, might explain why Abbot Hugh was kept waiting for so long that morning, before the King was in a position to receive him.13

As for the choice of meeting place, we have seen that Staines, on the north bank of the Thames, was being touted as a suitable place for negotiations between Langton and the barons as early as 27 May.14 Shortly after this, c.30 May, a monk of Bury St Edmunds sent to Staines in the expectation of meeting the King instead met there with William Marshal, the royalist earl Warenne, and the King's former keeper of the Bury estates.15 A Westminster Abbey estate, part way between the King at Windsor and the barons in London, Staines was not only the site of a bridge convenient for communication between the Middlesex and the Surrey/Berkshire sides of the river, but lay at the junction of four counties (Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Middlesex, and Surrey). It was precisely the sort of liminal location traditionally favoured for peace talks.16

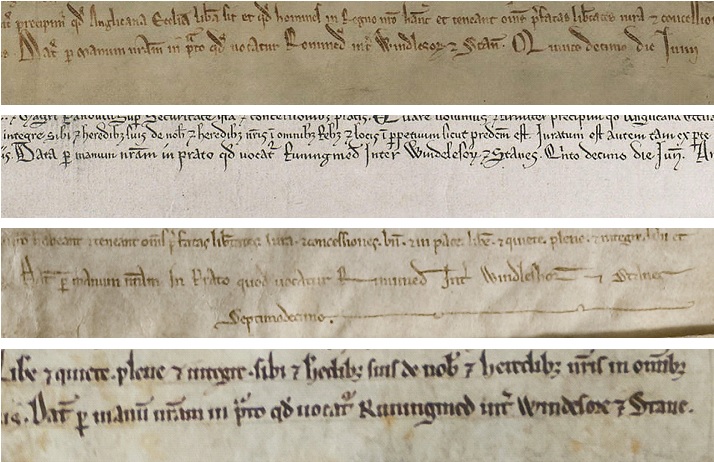

Neither quite land nor water, neither royal nor baronial, the meeting place is first specifically named on 15 June, in the dating clause to Magna Carta, where it is described as 'The meadow called Runnymede between Windsor and Staines'. Thereafter, through to the late thirteenth century, Magna Carta was far more frequently referred to in cartularies and statute books as 'Runnymede' or 'The Charter made at Runnymede', than it was as 'Magna Carta' ('The great charter).17 Even so, before June 1215, the name 'Runnymede' has no recorded existence. The Bury chronicler, for example, refers to it merely as 'Staines Meadow' or 'the meadow between Windsor and Staines'.18 Even to the scribes of Magna Carta, it was unfamiliar, two of them (Salisbury and Cotton Charter xiii.31a) preferring the form 'Runingmed', the other two (Lincoln and Cotton Augustus ii.106) preferring 'Runimed' or 'Ronimed'. A contemporary, translating Magna Carta into Anglo-Norman French, was so bemused by the name that he rendered it in the wholly unintelligible form ‘Roueninkmede’.19 The general assumption, apparently first proclaimed by the Reverend J.B. Johnston writing in the Times Literary Supplement for December 1917, thereafter taken up by Sir Frank Stenton and his colleagues in the standard guide to Surrey place-names, is that the name combines the Middle English 'runinge' ('taking counsel') and the Old English 'mæd' (or 'meadow'). As Stenton and his colleagues wrote, 'The name suggests that the mead had been the scene of earlier unrecorded assemblies, from which it had already earned this significant description'.20 This is possible. More plausibly, however, the name 'Runnymede' could have been newly minted in 1215 to describe precisely that 'meadow between Windsor and Staines' (in fact the water meadows lying between Cooper's Hill and the Thames, in the Surrey parish of Egham) where negotiations were held in May and June. In other words the 'runinge' in this 'mæed' was that of 1215, not some mythical 'runinge' of the Anglo-Saxon past. As this in turn would suggest, not only were the negotiations of June 1215 conducted in French, only later translated into Latin, but the place of negotiation was itself named in Middle English, subsequently translated into French and then into Latin. Truly, this was a cosmopolitan meeting.

To judge by the 'Articles of the Barons', and assuming that the date 10 June is correct for their sealing, already five days before 15 June, the King had agreed to the majority of the substantive clauses of Magna Carta. Not only this, but it had been agreed both that a 'committee' of twenty-five barons would be appointed to enforce the charter's terms, and that the archbishop, the bishops and Pandulf, the papal envoy, would issue written securities undertaking, on the barons' behalf, that the King would seek nothing from the Pope whereby these 'conventions' ('conuentiones') might be revoked or impaired.21 In other words, give or take a clause or two (including the highly significant clause 1 of Magna Carta on the liberties of the Church), and allowing for infelicities both of arrangement and phrasing, the 'Articles', as early as 10 June, rehearsed the vast majority of what was to be rehearsed more fully and felicitously five days later.22

As for other business this week, and here bearing in mind the later claims of the St Albans chroniclers that Magna Carta (in reality the draft or unofficial version of the charter known to Roger of Wendover) contained a clause demanding that oaths be taken to the twenty-five barons by the castellans of Northampton, Kenilworth, Nottingham and Scarborough, it is worth speculating whether these four castles remained under the threat of baronial siege.23 Certainly, Northampton had been besieged in May, and the King had recently spent time at Kenilworth, perhaps preparing for attack.24 That Scarborough remained of particular concern is shown in the present week by complicated calculations intended to ensure the payment of Geoffrey de Neville's garrison there - 59 serjeants, 10 crossbowmen and 10 knights - whose wages had in some cases remained unpaid since as long ago as 18 April. This money was to be supplied from the receipts of the vacant bishopric of Durham.25 Peter de Chanceaux, constable of Bristol, was commanded to pay the wages of seven knights and six serjeants, including two knights 'from Normandy who attend upon the King'.26 Despite the truce between King and barons, on 12 June custody of the lands of the late Hugh de Auberville was granted in such a way as to deprive the previous custodian, William of Eynsford, apparently himself now with the rebels.27 Other grants of land this week seem to have been routine, in one case intended to reward the loyalty of Hugh de Neville, the King's chief forester.28

Even so, we should be in no doubt that this remained a period of open war. In the far west, we receive our first indication from the chancery rolls of events unfolding in Wales. The Welsh chroniclers supply a detailed account of attacks made by Llywelyn ap Iorweth against Shrewsbury. Meanwhile, as early as 1 May, Giles de Braose, bishop of Hereford, is said to have attacked the castles of Pencelli, Abergavenny, White Castle, Grosmont and Skenfrith, all of which were taken. From here, the bishop proceeded via Radnor, Hay, Brecon, Builth and Blaenllynfi.29 In Dyfed, after c.27 May, there was an attack by Rhys Ieuanc (d.1222), the son of Gruffudd ap Rhys (d.1201) by his wife, Matilda de Braose (bishop Giles' sister), against Cemais and the Marshal lands in the far west, burning Kidwelly and various castles of Gower and Morgannwg. 30 It was apparently in response to this that, on 13 June, the King ordered William Marshal to secure the release of Rhys Gryg ap Rhys (d.1233, also known as Rhys Fychan), son of the Lord Rhys (d.1197) and uncle of Rhys Ieuanc, held prisoner since his capture at Carmarthen in 1213. Rhys Gryg was to be freed in return for surrendering two of his sons, and the sons of three of his closest allies, as hostages.31 Far from proving a reliable royal supporter, however, he in due course allied himself to Llywelyn.

Not only was the meeting at Runnymede a cosmopolitan affair, conducted in a mixture of Latin, French and possibly English, but the issues debated here extended both to greater Britain (Scotland, Ireland and Wales) and to ongoing fears over the attitude of the King of France. King John came to Runnymede attended by his Norman, Gascon and Flemish mercenaries. The barons and bishops included men from all parts of France (Brittany, the Touraine, Poitou) and from as far away as southern Italy (Master Pandulf). In this 800th anniversary year, it is well that we recall that Magna Carta was never a purely English achievement. Today, as the celebrations on 15 June 2015 will no doubt demonstrate, it belongs not just to England but to the world.

1 | RLC, i, 214-14b. |

2 | Expenses eventually audited in July: RLP, 150; RLC, i, 222. |

3 | Sarum Missal, ed. Wickham Legg, 161-9. |

4 | RLP, 214. |

5 | D.J. Cathcart King, Castellarium Anglicanum, 2 vols (New York, 1983), i, 191. Duffus Hardy ('Itinerary' in RLP, followed by J.C. Holt, Magna Carta (2nd edn., Cambridge, 1992), 243, and D.A. Carpenter, Magna Carta (London, 2015), 309, was clearly in error to suppose that the Mererton' of RLP, 142b-3 was Merton in Surrey. |

6 | RLP, 142b-3, also in Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 129. |

7 | C.R. Cheney, 'The Eve of Magna Carta', Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, xxxviii (1956), 311-41. For the 'Articles' themselves, the standard edition is now Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 432-40. |

8 | Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 243-4, 431-2, following in essence the outline of an argument first advanced by Holt, 'The Making of Magna Carta', English Historical Review, lxxii (1957), 401-22, an argument also accepted by Carpenter, Magna Carta (2015), 342. |

9 | Carpenter, 'The Dating and Making of Magna Carta', in Carpenter, The Reign of Henry III (London, 1996), 1-16, and most recently (following criticism by George Garnett and John Hudson), Carpenter's forthcoming 'Feature of the Month'. |

10 | RLP, 143, also in Foedera, 129. |

11 | RLP, 142b. |

12 | The Chronicle of the Election of Hugh Abbot of Bury St Edmunds and Later Bishop of Ely, ed. R.M. Thomson (Oxford, 1974), 168-73. |

13 | As noticed by Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 243-4. |

14 | RLP, 142, and cf. King John’s Diary and Itinerary for 24-30 May. |

15 | Chronicle of the Election of Hugh, ed. Thomson, 168-9. |

16 | For instances here, see J.E.M. Benham, ‘Anglo-French Peace Conferences in the Twelfth Century’, Anglo-Norman Studies, xxvii (2005), 52-67; D.E. Thornton, ‘Edgar and the Eight Kings, AD 973: Textus et Dramatis Personae’, and J. Barrow, ‘Chester’s Earliest Regatta? Edgar’s Dee-Rowing Revisited’, Early Medieval History, x (2001), 49-79 and 81-93. |

17 | Carpenter, Magna Carta (2015), 6-7. |

18 | Chronicle of the Election of Hugh, ed. Thomson, 170 ('in prato de Stanes ..... in prato sito inter Wyndlesoure et Stanes'). |

19 | J.C. Holt, 'A Vernacular French Text of Magna Carta', English Historical Review, lxxxix (1974), 364, reprinted in Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government (London, 1985), 257. For the forms favoured in the royal chancery, see 'Runemed' (RLP 143b), 'Runimed' (RC, 210b; RLP, 144, 180b; RLC, i, 215b-16; Rot.Ob., 553), and 'Runyngemed' (RLC, i, 216). |

20 | The Place-Names of Surrey, ed. J.E.B. Gover, A. Mawer and F.M. Stenton in collaboration with Arthur Bonner, English Place-Name Society xi (1934, new edn. 1982), 124. |

21 | Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 432-40, esp. p.40. |

22 | For a full comparison between the 'Articles' and the text of Magna Carta, see a forthcoming paper by John Hudson. In the meantime, see Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 285-91, and especially Carpenter, Magna Carta (2015), 342-61. |

23 | Roger of Wendover, Flores Historiarum, ed. H.O. Coxe (4 vols., London, 1842),, iii, 317 (Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard (7 vols., Rolls series, 1872–83), ii, 603), as noted by Carpenter (Magna Carta (2015), 367), perhaps reflected in the belief of the author of the Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, (ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 150), that it was agreed at Runnymede that no royal bailiff was to be appointed save through the twenty-five. |

24 | See King John’s Diary and Itinerary for 29 March-4 April, 3-9 May, 10-16 May. |

25 | RLC, i, 214. |

26 | RLC, i, 214-14b: 'duobus militibus qui nobiscum sunt de Norm(annia)'. |

27 | RLC, i, 214, and cf. RLP, 195b; RLC, i, 216b, 295, for restoration to William, a fortnight later, himself by September 1216 apparently a rebel ransomed from the King's prison. |

28 | RLC, i, 214, including the grant to Hugh of the former royal demesne manor of Somerton in Somerset. |

29 | Brut Y Tywysogyon or the Chronicle of the Princes: Peniarth MS. 20 Version, ed. T. Jones (Cardiff, 1952), 90; Brut Y Tywysogyon or the Chronicle of the Princes: Red Book of Hergest Version, ed. T. Jones (Cardiff, 1955), 202-3. |

30 | Brut: Peniarth Version, 90; Brut: Red Book Version, 202-3. |

31 | RLP, 143, where Rhys Gryg is referred to as Rhys 'Boscan'. His release is noticed by Brut: Peniarth Version, 91; Brut: Red Book Version, 204-5, where it is said to have been made in return for his surrendering his son and two other hostages, and for the capture of Rhys Gryg in 1213, Brut: Peniarth Version, 88; Brut; Red Book Version, 198-9. For the relationships and native politics here, see The Acts of Welsh Rulers 1120-1283, ed. Huw Pryce and Charles Insley (Cardiff, 2005), pp.l (table 3), 9-10. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)