The rebels seize London

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

17 May 1215 |

RLP, 136b-7, 141b |

||

17-19 May 1215 |

RLP, 137-7b |

||

19-20 May 1215 |

RLP, 137b, 141b |

||

21-22 May 1215 |

RLP, 137b-8 |

||

22-23 May 1215 |

RLP, 138 |

||

23-24 May 1215 |

RLP, 138 |

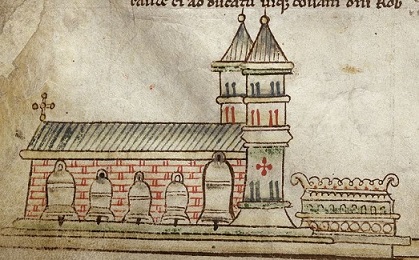

This week, no charters were copied on to the Charter Roll, and the Close Roll peters off into illegibility after 16 May.1 As a result, we depend upon just over thirty entries in the Patent Roll for what was to prove a momentous seven days in English history. As the King would have heard in the introit to Mass, at Marlborough on Sunday 17 May, in paraphrase of the words of Psalm 96, 'Oh sing to the Lord a new song, because he has done such marvellous things; he has revealed his justice before the face of all people, Alleluia!'2 The same words would have been spoken 60 miles away in London where, around dawn that day, a baronial army, recently decamped from Northampton, broke into the city and seized what was already England's capital. The chronicle sources for this event are translated elsewhere.3 They suggest that the fall of London was the result of conspiracy between the barons and various of the greater London merchants, disgusted with John's policies and in particular with taxation and the disruption to trade with France and Flanders brought about by recent wars. Robert fitz Walter, hereditary constable of Baynard's Castle just south of St Paul's, was perhaps the most significant point of contact between citizens and barons. According to a contemporary collection of London laws, Robert served, even before 1215, as hereditary standard bearer of the city: yet another reminder of the way in which flags and symbols were crucial to rebel solidarity.4 Robert's hereditary association as standard bearer with the canons of Holy Trinity Aldgate may indeed explain how it came about on 17 May 1215 that the Aldgate entrance to the city was left so conveniently unprotected.5 Nor was Robert alone amongst the rebels in having close London contacts. Richard de Montfichet, hereditary constable of Montfichet's Tower, just to the north of Baynard's Castle, was another of the barons later numbered amongst the twenty-five of Runnymede.6 So was Geoffrey de Mandeville, claiming hereditary office as constable of the Tower of London. So was the mayor of London.7 The chancellor of St Paul's, Master Gervase of Howbridge, in due course elected dean during the rebel occupation, was to suffer excommunication for his support of rebellion having, as early as 1212, been exiled as a fellow conspirator of Robert fitz Walter in the alleged plot against the life of King John.8 He was presumably a kinsman of William of Howbridge, named by Roger of Wendover as one of the earliest rebels and himself witness to a charter of Geoffrey de Mandeville involving property in London's Friday Street, apparently issued whilst London was under rebel occupation, after May 1215.9 Master Simon Langton, brother of archbishop Stephen, was another canon of St Paul's enthusiastically engaged in the rebel cause.10

Oblivious to what was going on in his capital city, on 17 May the King dispatched letters to William earl of Salisbury and to the mayor, sheriffs and barons of London, advising them that he was sending them instructions via Walter bishop of Coventry and Hubert de Burgh, recently returned from Poitou.11 News of the rebel seizure nonetheless travelled fast, so that by the time he reached Freemantle, on Monday 18 May, the King was in a position to warn Roland Bloet, then keeping Knepp in Sussex that, in light of the surrender of London to the rebels on the previous morning, he should take all his provisions from Knepp to Bramber Castle for safe-keeping, demolishing the King's houses meanwhile.12 Foreigners arriving in England were commanded to be obedient to Roland, who was himself instructed to receive William earl Warenne or his men, should they seek shelter at either Knepp or Bramber.13

The fear may have been that, as was to be the case in 1264, the rebels, having taken London, would cut communications between the King and his castles in the south east, striking southwards towards the Sussex coast in the hope of seizing a port where foreign allies could be landed. On the same day that the King wrote to Knepp, the men of Chichester were commanded to defend their town with the assistance of Matthew fitz Herbert.14 By the following Saturday, 23 May, John was issuing orders for reprisals to be taken whenever and wherever possible against the Londoners 'who have fraudulently and seditiously departed our service'.15 In the meantime, the seizure of London was a truly game-changing event. Not only did it mean that the treasury and Exchequer were now in rebel hands, but with the fall to the rebels of the palace and abbey church at Westminster, there was now a threat that a French claimant, most likely Louis, son of King Philip, could sail unopposed up the Thames to Westminster Abbey, and there be crowned in the traditional coronation church of England's kings. It was the loss of London above all other things that forced John into negotiations with the barons, leading to the meetings at Runnymede three and a half weeks later.

In the immediate term, it seems to have brought a pause at Freemantle (in Kingsclere) to the King's progress eastwards from Marlborough, and led to a brief diversion to Winchester on 19-20 May, perhaps so that the ancient capital of England's kings could be made ready to serve in place of the lost treasury and Exchequer at Westminster. The men of Winchester were pacified with the release of a local man, Luke of Morestead, formerly held in the King's prison at Nottingham.16 In return, Luke offered 60 marks for the defence of Winchester, with the citizens pledging his future good conduct.17 The men of Winchester also obtained a grant of immunity from distraint for debt save for those debts that they themselves had directly incurred.18 Similar leniency was shown on the following day, 21 May, to local men released from the King's prison at Odiham.19 Timber was commanded from the Hampshire forests for the defence of Winchester castle.20 The commands involving Luke of Morestead, meanwhile, reveal something of the problems that now engulfed the chancery following the loss of its headquarters, and many of its records, at Westminster. The written pledges on Luke's behalf, issued by the men of Winchester at Hyde Abbey on 20 May, were released to Odo, clerk of the King's wardrobe.21 The copy of the orders for Luke's release carried a postscript, greeting William Cuckoo Well, for the past few weeks chief keeper of the King's rolls.22

The possibility of reconciliation continued to be held out to particular rebels. On 17 May, Henry of Braybrooke was granted letters of safe conduct to speak with the King and Geoffrey de Martigny, the King's constable at Northampton, was ordered to receive back any of the King's 'enemies' who wished to return to fealty.23 A few days later, Simon of Pattishall, a former royal justice whose property had been seized by the King on 15 May, was granted safe conducts and a promise that if his land had been confiscated in error, he would immediately be restored to possession.24

For the most part, however, the King continued to focus upon the strengthening of castles and the importation of mercenaries. Particular attention was paid this week to the garrisoning of Bristol Castle.25 This perhaps reflected fears on the Welsh marches where Walter de Lacy, Hugh de Mortimer, John of Monmouth and Roger of Clifford were each promised a war horse from the King's stables at Gloucester.26 Hugh de Mortimer was also assured possession of the Gloucestershire manors of Tetbury and Hampnett as the right of his wife, a daughter of William de Braose.27 Further north, the earl of Chester was granted the castle at Newcastle-under-Lyme, and Horston Castle, in Horsley north of Derby, was released to William II de Ferrers, earl of Derby, so that he could keep his wife, a sister of earl Ranulph of Chester, in safety there.28 Robert of Béthune and Baldwin d'Aire, two of the more prominent barons of southern Flanders, were enticed to England with offers of annual fees of £200.29

Rather more surprisingly, the constables of Dover and Canterbury, and Reginald of Cornhill as constable of Rochester, were ordered to supply hospitality to a man named Robert 'de Drewes' should he land in England.30 If this was Robert of Dreux, brother of the duke of Brittany, captured at Nantes in the summer of 1214 and held prisoner in England until ransomed in March 1215, then his expected return to England must be accounted a truly remarkable event.31 In the event, Robert of Dreux crossed to England in 1216, not as an ally of John but as a member of Prince Louis' invasion force.32 No less remarkable was an order issued this week to Peter de Maulay, to permit William de St John, Robert de Ropsley and Robert of Burgate access at Corfe to the King's niece, Eleanor of Brittany.33 Held captive in England since the arrest of her brother, Arthur of Brittany, in 1202, Eleanor was destined never to be released from prison, where she died in 1241. In 1214, aged twenty or so, she had been taken to Poitou on John's expedition, as a diplomatic pawn in the King's negotiations with the Bretons and with Peter de Dreux, titular duke of Brittany.34 Quite why she was brought back into play in May 1215 remains unclear. Possibly, the orders of 21 May were intended to reassure the King's critics that Eleanor was well kept and had not suffered the fate of her brother, Arthur. More likely, they were related to the coming to England of Robert of Dreux, brother of the duke of Brittany.35 Of the three knights sent to Eleanor at Corfe, William de St John was subsequently to join the rebels. Robert of Ropsley, by contrast, occurs in the preamble to Magna Carta, at Runnymede in June 1215, as one of the royalists on whose advice the charter was issued.

In two further items of business this week, prebends at York and Southwell were conferred upon Peter of Ferentino, nephew of the papal chamberlain, Master Stephen of Fossanova, and upon Stephen of Lexinton.36 The first of these promotions was intended to reward one of the King's principal contacts at the Roman curia.37 The second marks the very earliest appearance by Stephen of Lexinton (d.1258), a native of Laxton in Nottinghamshire, a Paris-trained clerk in due course to enjoy a distinguished career as abbot of Clairvaux.38

1 | For the mutilated end of the Close Roll, RLC, i, 200b. |

2 | The Sarum Missal Edited from Three Early Manuscripts, ed. J. Wickham Legg (Oxford, 1916), 148-9. |

3 | See the Feature of the Month, 'The Rebel Seizure of London'. |

4 | Munimenta Gildhallae Londoniensis, ed. Riley, 3 vols (London, 1860-2), ii part 1 (Liber Custumarum), pp.lxxvi-lxxxiv, 147-9, from the claims made by a later Robert fitz Walter as lord of Baynard's Castle, 1303, and cf. W. Page, London: Its Origin and Early Development (London, 1923), 190-1, 193; C.N.L. Brooke and G. Keir, London 800-1216: The Shaping of a City (London, 1975), 216. |

5 | Munimenta Gildhallae, ed. Riley, ii part 1, pp.lxxix, 149. |

6 | For earlier connections during the civil war of 1173-4 between Richard de Montfichet's grandfather and his close kinsman of the Clare family, a family from which Robert fitz Walter himself sprang, see Brooke, London, 42, 215; N. C. Vincent, ‘Montfichet, Richard de (b. after 1190, d. 1267)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn., Oct 2005) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/19044, accessed 20 May 2015]. |

7 | Probably Serlo the Mercer. Cf. Brooke, London, 256-7, 376. |

8 | RLC, i, 165b (excommunicated in the Essex county court alongside Robert fitz Walter, the archdeacon of Hereford, Henry de Alneto, Walter de Valognes, John of Eggesfield, William and Philip of Howbridge, Ralph Gubiun and Robert de Cunar(iis), in the autumn of 1213); J. Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300, ed. D. E. Greenway (London, 1999), i (St Paul's London), 6, 26, 56, where his appointment as dean is dated after September 1216. In reality, he seems already to have been dean by May 1216: Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 171, and cf. The Letters and Charters of the Legate Guala Bicchieri, Papal Legate in England, 1216-1218, ed. N. C. Vincent (Woodbridge, 1996), 34-5 no.45, 41-2 no.54, 89-90 no.121. |

9 | Roger of Wendover, Flores Historiarum, ed. H.O. Coxe (4 vols., London, 1842), iii, 297. For Geoffrey de Mandeville's charter, see Cartulary of St Bartholomew's Hospital, ed. N.J.M. Kerling (London 1973), 73 no.695, a grant elsewhere (Ibid., 165 appendix I no.183) dated to the year 12 John (1210-11), but issued by Geoffrey de Mandeville as earl of Gloucester, so 1214 X 1216, probably 1215, during the rebel occupation of London. |

10 | Letters of the Legate Guala, ed. Vincent, pp.lxiii-iv; Le Neve, Fasti, ed. Greenway, i, 50. |

11 | RLP, 137. For Hubert de Burgh, who had returned to England by 17 May, see RLP, 136b-7. |

12 | RLP, 137b. |

13 | RLP, 137b-8. |

14 | RLP, 137, and cf. orders of the same day to William fitz John and William of Wrotham, keeper of the King's ships, to receive instructions from the chancellor, Richard Marsh. |

15 | RLP, 137b: 'Rex omnibus bailliuis et fidelibus suis has etc. Sciatis quod ciues London' a nobis et seruicio nostro et fidelitate nostra fraudulenter et sediciose communiter recesserunt, et ideo vobis mandamus quatinus cum ipsi vel ministri vel catalla eorum per vos transitum fecerint, eis omne malum et dedecus quod facere poteritis faciatis tanquam inimicis nostris. Et in huius etc vob(is) in(de) mittimus. T(este) ut supra'. |

16 | RLP, 137b, |

17 | RLP, 141b. |

18 | RLP, 137b, duly incorporated into a charter in favour of the citizens of Winchester, 18 July 1215: RC, 217. |

19 | RLP, 137b-8. |

20 | RLP, 137b. |

21 | RLP, 141b. |

22 | RLP, 137b: 'Saluto vos Willelme Kukke Wel', and for William as keeper of the rolls, see King John's diary and itinerary, 19-25 April. |

23 | RLP, 136b-7. |

24 | RLP, 138, negotiated through the intercession of the abbot of Woburn, and for the seizure of Simon's land at Waddesdon in Buckinghamshire on 15 May, RLC, i, 200. |

25 | RLP, 137-8, orders of 17, 22 and 23 May. |

26 | RLP, 137. |

27 | RLP, 137, and for the manors, previously held in custody by Giles de Braose, bishop of Hereford, VCH Gloucestershire, ix, 83, citing RLC, i, 140. |

28 | RLP, 137-7b. |

29 | RLP, 138. Baldwin was presumably a native of Ayre-sur-Lys (Pas-de-Calais), just north of Béthune. The original of the letters promising £200 to Robert of Béthune, dated at Reading on 23 May 1215, was listed in 1784 by the Lille archivist, Denis Godefroy: Lille Archives départementales du Nord B 174 p. 354 n° 299: ‘Orig. en parch., scellé d’un morceau du grand scel de ce roi en cire blanche, pendant à simple queue de parchemin’, as drawn to my attention by Jean-Philip Nieuss. |

30 | RLP, 138. |

31 | Histoire des Ducs, ed. Michel, 143-5, remarking on the leniency of his treatment as a prisoner in England, permitted to hunt and hawk, and cf. King John's Diary and Itinerary for 15-21 June, 10-16 August, 31 August-6 September 1214, 11-17 January, 18-24 January, 8-14 February and 22-28 February, 8-14 March, 5-11 April 1215. |

32 | Histoire des Ducs, ed. Michel, 166, 175, 177-9, 188, 202, and p.208 (noting his return for the translation of St Thomas' relics at Canterbury in 1220), and cf. RLP, 196. |

33 | RLP, 137b. |

34 | G. Seabourne, 'Eleanor of Brittany and her Treatment by King John and Henry III', Nottingham Medieval Studies, li (2007), 73-110. |

35 | See here King John's Diary and Itinerary for 24-30 May (forthcoming). |

36 | RLP, 138, and cf. Le Neve, Fasti, ed. Greenway, vi (York), 89. |

37 | For Stephen of Fossanova, see Letters of Guala, ed. Vincent, pp.lxix, 101-3 no.140; Diplomatic Documents Preserved in the Public Record Office, ed. P. Chaplais (London,1964), nos 17-19, 29; C. R. Cheney, Pope Innocent III and England (Stuttgart, 1976), 36, 93-4. |

38 | C. H. Lawrence, ‘Lexinton, Stephen of (c.1198–1258)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn., 2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16617, accessed 20 May 2015]. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)