The terrible end of Hugh de Boves

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

20 September 1215 - 26 September 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

20-22 Sep 1215 |

RLP, 155b-6; RLC, i, 229 |

||

22 Sep 1215 |

RLC, i, 229 |

||

23-28 Sep 1215 |

RC, 219-19b; RLP, 156-6b; RLC, i, 229-9b |

The King remained in east Kent for the whole of the present week. On Thursday 24 September, as we are informed by the chronicler known as the 'Anonymous of Béthune', the mercenary captain, Hugh de Boves, embarked from the Flemish coast with a large body of knights and serjeants recruited in Flanders.1 Preparations for this long-anticipated event can be detected on 20 September in the King's commands to the men of Dunwich, Yarmouth and the Cinque Ports to follow instructions about to be delivered by Nicholas fitz Robert (alias Nicholas of Dunwich) and Alexander of Rye, presumably concerning the transport of the King's mercenaries across the Channel.2 On 22 September, letters of safe conduct were issued for Alice of Béthune, the wife of William Marshal the younger, travelling from her native Flanders into England.3 There were also safe conducts for John de 'Chambli', coming into England with arms and horses, and, beginning on Monday 21 September, several commands to Robert de Barreville, apparently deputed by Hubert de Burgh to the custody of Dover castle. Here the King requested armour and arms for various of his mercenaries, including those attached to Savaric de Mauléon.4 Some of this armour is said to have been brought south from Northampton, perhaps at the time that the alien constable of Northampton, Geoffrey de Martigny, had taken ship for France.5 Robert was also asked, in peremptory terms, for news of the King's son who had been left in his care (presumably here referring to Richard, the future earl of Cornwall, who in August had travelled in the King's company, by sea from Southampton to Kent).6 Robert, together with the King's tailor, William Scissor, recently granted land seized from Roger Huscarl, were also made responsible for supplying the King with crossbows, crossbow bolts, food and clothing, including what seems to have been the King's own armour, all of which was to be sent from Dover to Canterbury.7 Given the King's well-known fondness for falconry, we might the inclusion in these commands of a request that William send all the bells ('noelettas') for hawks' that he had at his disposal.8

Besides the land previously assigned to Roger Huscarl, we find what may have been forced seizures of land in Wiltshire from William fitz Alan, at Goodnestone ('Godwineston') near Chilham in Kent, and at 'Selves' in Kent.9 A continued concern to curry favour with the papacy is revealed this week both with commands for £136 to be paid to the Pope in arrears for Peter's Pence owing from the diocese of Lincoln, and with a grant of 200 marks in ecclesiastical rents to the Pope's foundation at St Sixtus in Rome, pending the assignment of an equivalent sum assigned from the church of Bamburgh as soon as it should be vacated by the papal chamberlain, Stephen of Fossanova.10 This award, made at Canterbury on Thursday 24 September, was set out in a charter witnessed by the earls of Salisbury and Aumale, Hubert de Burgh, Savaric de Mauléon, Warin fitz Gerald, Fawkes de Breauté and Stephen Harengod: the last such royal charter to be entered in the chancery rolls before January 1216 and perhaps, like the use of the King's privy seal this week, marking the departure of the chancellor, Richard Marsh, for the great Church council summoned to Rome.11 In the cathedral churches of York and Ely, where episcopal elections continued to be contested, the King interfered to award patronage to favoured clerks: Alexander of Dorset and Richard de Tosny.12

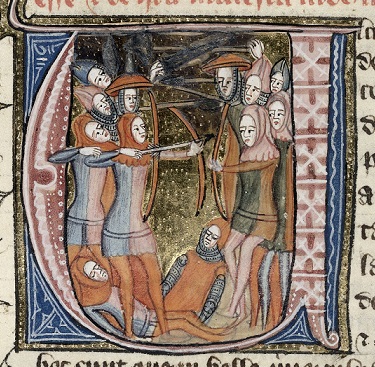

The most dramatic events of this week occurred at sea. Having embarked from Flanders, perhaps from Calais, on Thursday, 24 September, Hugh de Boves and his ship, carrying at least 36 Flemish knights, were caught in a terrible storm on Friday 25 September, and by Saturday 26 had been shipwrecked off the coast of Dunwich. Hugh himself was drowned. Those stranded by the outgoing tide on the sands feared not just the perils of the sea but the crowds on shore who gathered, clearly in the hope of wreckage and the spoliation of what remained to plunder. At least one ship in the fleet was carried off in the direction of Denmark. Those on board were so afraid that they communally vowed themselves crusaders. The King, so we are told, was by this time at Canterbury, alarmed by news that the 'Northerners' had now left London and had not only occupied Rochester but had advanced along Watling Street as far east as Ospringe.13

1 | Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 153-4, and c.f. King John’s Diary and Itinerary, 30 August - 5 September. |

2 | RLP, 155b-6. |

3 | RLP, 156. |

4 | RLP, 156; RLC, i, 229, including armour for Nicholas/Colin de Molis; Luseus 'the hermit' attached to Savaric de Mauléon; Peter de Craon serving with the count of Aumale; Wilekin May, Robert de Stanton and Adam Capreol granted lodging in Dover castle, and for Joldewin de Doué, himself, together with Gilbert of Kentwell, apparently serving in some capacity alongside Robert de Barreville at Dover castle. |

5 | RLC, i, 229, and cf. King John’s Diary and Itinerary 13-19 September. |

6 | RLC, i, 229, and cf. King John’s Diary and Itinerary 30 August - 5 September. |

7 | RLC, i, 229-9b, including clothing: 'two of the King's light doublets most recently made, and linen thigh armour, and shoulder straps, and a crossbow winch and a helmet' ('duos de leuibus perpunctis domini regis qui ultimo facti fuerunt et unas lineas quisseras et unas espaudleras et unum tornum et unam galeam'), and cf. RLC. i, 229b, for orders to Roger the almoner 'hastily' to supply the King with wine. |

8 | RLC, i, 229b, and cf. orders this week concerning the King's falconers at Wilton and Corfe: RLC, i, 229-9b. |

9 | RLC, i, 229-9b. |

10 | RC, 219-19b; RLP, 156; RLC, i, 229b. |

11 | RC, 219-19b, and for the use of the privy seal on 23 September, RLP, 156. For a ship taking John Marshal, one of the King's envoys to the Pope appointed in the previous week, from either Portsmouth or Southampton into France, see RLC, i, 229. |

12 | RLP, 156, in the case of the church of Chesterton outside Cambridge, directed to the officials of the bishopric rather than the bishop, suggesting that the King may already have reneged on the approval that he previously granted Master Robert of York as bishop-elect: The Letters and Charters of Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, Papal Legate in England 1216-1218, ed. N. Vincent, Canterbury and York Society 83 (1996), no.25, and cf. no.16 for the church of Chesterton. |

13 | Histoire des ducs, ed. Michel, 154-7. For Calais specified as the point of Hugh's embarkation, see Roger of Wendover, Flores Historiarum, ed. H.O. Coxe (4 vols., London, 1842), iii, 332-3, an account clearly over-dramatized with an account of how Hugh and his men brought over a multitude of women and infants, intending the total disinheritance of the English. See also Chronica de Mailros, ed. J. Stevenson, Bannatyne Club (Edinburgh, 1835), 119-20. For evidence that Hugh's drowning formed part of a widely circulated newsletter, now lost, see the specification that he sank 'like lead in the troubled waters': Dunstable annalist, in Annales Monastici, ed. H.R. Luard, 5 vols. (London, 1864-9), iii, 45 ('quasi plumbum in aquis vehementis submersus est'; Radulphi de Coggeshall Chronicon Anglicanum, ed. J. Stevenson (Rolls ser., 1875), 175 ('submersus est quasi plumbum in aquis vehementibus').

|

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)