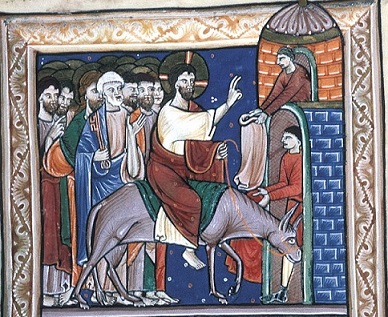

John enters Oxford on Palm Sunday

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

12 April 1215 - 18 April 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

12-13 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 132-2b; RLC, i, 194-4b, 195b |

||

13-14 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 132b-3; RLC, i, 194b-5 |

||

14-15 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 132b-3; RLC, i, 195-5b |

||

15 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 133; RLC, i, 195 |

RLC, i, 195 supplies a writ supposedly dated at Windsor on 5, recte 15 April. |

|

16-18 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 133-4; RLC, i, 195-5b, 203 |

This was Holy Week. The King was in Oxford for Palm Sunday, returning to London by Maunday Thursday to spend Easter itself, the climax of the liturgical year, in the New Temple. This was a time of heightened expectations as well as of ceremonial. John himself may have instituted (or more likely inherited) an annual gift gifting ceremony for paupers on Maunday Thursday - the origins of the royal Maundy still practised today.1 In the present year, there are also signs that both Maunday Thursday and Good Friday were marked by a deliberate amnesty for royal prisoners, including all who were not knights or gentry (gentiles) held since the siege of Carrickfergus in 1210, and a man named Benedict 'the Moor', imprisoned for the past several years for poor keeping of the King's hay at Beskwood in Nottinghamshire.2 It is at least possible that the King was acting here in deliberate imitation of New Testament Jerusalem whose custom, as recorded in the Gospels, had been to release a prisoner at the time of Passover. The story of Barabbas, from Luke 22-23, formed part of the set reading in the Sarum office for Maunday Thursday. The fact that Luke (23:19) refers to Barabbas as a prisoner held both for murder and for 'insurrection' (seditio ... in ciuitate) might have been remarked with particular interest in 1215.

Both Palm Sunday (commemorating Christ's return to Jerusalem with an elaborate liturgy including dramatized reading of the Passion narrative from the Gospel of St Matthew) and Good Friday (commemorating the Crucifixion) had in the past been associated with expressions of anti-Jewish feeling, not least in 1190 at the time of the massacre of the Jews of York.3 There is reason to suspect similar tensions in 1215. On Monday 13 April, the sheriff of Oxfordshire was ordered to grant the prior of St Frideswide rents and lands in Oxford that had previously been in the hands of the Jews but that had since been seized 'on the day when the Jews were taken (capti) by our command'.4 This, incidentally, suggests that Palm Sunday itself was spent by the King in St Frideswide's, a reminder that in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries kings regularly entered the city of Oxford. Only later, from the 1260s onwards, did the legend grow that the curse of Frideswide (an Anglo-Saxon princess threatened with abduction by Aethelbald King of Mercia) forbade all future kings from entering Oxford.5 The chronicler William Rishanger was to blame the defeat of Henry III at Lewes in 1264 upon the King's precipitate entry into Oxford.6 It is a possibility that the legend of Frideswide's curse owed at least something to the association between King John's visit to Oxford, in April 1215, and his subsequent humiliation at Runnymede. Given that by April 1215, King John was a pledged crusader, and given also that the Palm Sunday celebrations in the Latin church of Jerusalem included a solemn procession or 'adventus' for the kings of Jerusalem, we might speculate that John's entry into Oxford on Palm Sunday 1215 was made particularly memorable.7 Meanwhile, the collect for the Friday before Palm Sunday might have had particular resonance for the King: ‘Deliver me not, Oh Lord, into the will of mine adversaries, for there are false witnesses risen up against me, and such as speak wrong’.8

Of the business conducted this week, the most significant continued to concern the garrisoning of Midland castles now clearly considered at risk of an imminent rebel attack. From Wallingford, on 14 April, the King wrote to ten local knights requiring them to perform the castle guard that they owed in garrisoning Wallingford castle, now provisioned with corn and salt pork and 10,000 crossbow bolt.9 A further 10,000 crossbow bolts were sent to Northampton, and arrangements made for the constable, Geoffrey de Martigny, to be supplied with men, provisions and timber with which to defend the castle.10 That Northampton was considered particularly vulnerable can be gauged from letters sent on 14 April to the sheriff of Northamptonshire, Henry of Braybrooke, warning him that any deficiency in the castle's garrisoning would redound to his particular shame.11 On 15 March, the King dispatched messages to ensure the proper garrisoning of Rockingham.12 Both Berkhamstead and Mountsorrel Castle in Leicestershire were supplied with timber, and Kenilworth and Hanley Castle in Worcestershire with wine.13 Colchester was ordered enclosed with wooden defences.14 Further north, instructions were sent to Philip Mark at Nottingham to use part of the treasure in his custody to supply £105 required to pay the wages of knights and serjeants at Scarborough, ensuring that the money was closely guarded on its journey northwards.15 After more than six months of virtual self-government, the bishopric of Norwich was at last taken into direct royal custody, and at Ely, besides making provision for the appointment of royalist keepers, the King renewed his appeal against any attempts by the monks to elect Master Robert of York, in due course to obtain recognition as bishop-elect only briefly, on the field of Runnymede.16 The Bishop of Winchester, Peter des Roches, and the Hampshire baron (and future rebel), William de St John, were sent to Southwick Priory to arrange an election, and at Barking, whose nuns continued to resist attempts to impose a royalist candidate, custody of the vacant abbey passed to William bishop of London, in return for letters from William presumably promising in no way to infringe upon the King's rights.17 At Bangor, the King accepted the canons' election of the abbot of Whitland, who he had specifically urged upon them as his own candidate.18 Both this and the ongoing appeals over Ely were notified to Stephen Langton, at least with the pretence of continuing to seek archiepiscopal sanction for the King's dealings with the Church.19

Other gestures of appeasement were attempted. Besides the prisoners released on Maunday Thursday and Good Friday, hostages were restored to Earl David of Huntingdon, and to the Anglo-Norman knight, Ingelram de Préaux.20 At the petition of William earl of Salisbury, himself imprisoned after Bouvines, a French prisoner taken by the King at the Bridge of Nantes in June 1214 was released in Poitou in order to effect an exchange of hostages apparently sought by another of the victims of Bouvines.21 Channels of communication with the future rebels remained open, or at least intelligence as to future rebel intentions remained unsure. On 13 April, the Exchequer was commanded to make allowance to Robert de Ros for his keeping of Carlisle Castle, the costs here to be deducted from his debts as farmer of the city of Carlisle.22 William de Forz, Count of Aumale, was promised repayment of money taken from his land whilst in royal custody, and seisin of the lands of a subtenant seized in Cornwall.23 Roger de Merlay received licence to empark an estate in Northumberland.24 In Bedfordshire, a widow and her land were transferred to the lordship of William de Ferrers, earl of Derbyshire, provided that the widow and her son and heir would agree to this transfer.25

Amongst the more reliable of the barons, Ranulf earl of Chester was promised the restoration of manors claimed as the inheritance of his wife, and William earl of Salisbury was granted the scutage taken from the tenants of his honour of Trowbridge.26 As part of a wider gesture of appeasement, in due course to be extended to the men of Cornwall, the sheriff of Devon was instructed to ensure the men of Devon all liberties that they claimed by virtue of earlier royal charters, this privilege to last for at least three weeks from the coming Easter.27 Most significantly of all, on Palm Sunday, 12 April, the King at last commanded the restoration to Walter de Lacy of the castle of Ludlow in Shropshire, the principal Lacy seat in the Welsh Marches and the most potent symbol of the rapprochement that John had effected with the Lacy family over the past few months.28

A number of charters can be assumed to have been issued this week. One, now lost, seems to have granted the nuns of Wherwell in Hampshire quittance from various burdens and an annual four day fair.29 Roger de Merlay's new park was perhaps granted by charter, also now lost.30 The only one of these instruments that seems to survive, in cartulary copies rather than in the chancery rolls, confirmed to the monks of Peterborough the disafforestation of Nassaburgh, first referred to a few weeks earlier, now embodied in charter that further granted the monks the right to assart 100 acres of land in Cottingham and Great Easton, on either side of the Northamptonshire-Leicestershire border.31 Issued at Oxford on Palm Sunday, this was witnessed by Stephen Langton, by the royalist bishops of London, Winchester, Worcester and Coventry, by the royalist earls of Chester, Pembroke, Salisbury, Warenne and Arundel, but also by the waverers or future rebels, Roger Bigod earl of Norfolk, William Ferrars earl of Derby, and Richard de Clare earl of Hertford.32 The final battle lines between loyalists and rebels had still to be drawn.

1 | See here Arnold Kellet, 'King John in Knaresborough: The First Known Royal Maundy', Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, lxii (1990), 69-90, and idem, 'King John's Maundy', History Today, xl (4 April 1990), at <http://www.historytoday.com/arnold-kellet/king-johns-maundy>. |

2 | RLP, 133-133b, three letters, all dated to Thursday 16 April or Friday 17 April. |

3 | N. Vincent, ‘William of Newburgh, Josephus and the New Titus’, in S. Rees Jones and S. Watson (eds.), Christians and Jews in Angevin England (York, 2012), 57-90, esp. pp.71-2. |

4 | RLC, i, 194b. |

5 | John Blair, ‘Frithuswith (d. 727)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10183, accessed 19 April 2015]. |

6 | William Rishanger, Chronica et Annales, ed. H.T. Riley (London, 1865), 20. |

7 | For Jerusalem, see Iris Shagrir, 'Adventus in Jerusalem: The Palm Sunday Celebrations in Latin Jerusalem', Journal of Medieval History, xli (2015), 1-20. |

8 | The Sarum Missal: Edited from Three Early Manuscripts, ed. J. Wickham Legg (Oxford, 1916), 90–1; Missale ad usum insignis ecclesiae Eboracensis, ed. W. Henderson, 2 vols., Surtees Society lix-lx (1872-4), i, 82–3: ‘Ne tradideris me, Domine, in animas persequentium me: quia insurrexerunt in me testes iniqui, et mentita est iniquitas sibi’, and compare the opening collect for this same Friday, ‘Miserere michi, Domine, quoniam tribulor: libera me, et eripe me de manibus inimicorum meorum: et a persequentibus me, Domine, non confundar, quoniam inuocaui te’, closely related to the Epistle for that day, Jeremiah 17. 13–18, as noted by Vincent, 'William of Newburgh', 72n. |

9 | RLP, 132b; RLC, i, 195, and cf. RLC, i, 195, instructions that Walter Foliot and his wife and familiars were to be accommodated in the chamber of Wallingford Castle where the King's wardrobe had previously been kept. |

10 | RLC, i, 195-5b. |

11 | RLC, i, 195b, 'et vos precipue vestram ad hoc diligentiam interponatis quia nisi garnistura illa bene custodiatur et sapienter expendatur, ad vos gravius quam ad aliquem alium nos inde capiemus'. |

12 | RLP, 133. |

13 | RLC, i, 194, 195. |

14 | RLC, i, 195. |

15 | RLC, i, 195. |

16 | RLP, 132b-3, and for Robert, see The Letters and Charters of Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, Papal Legate in England 1216-1218, ed. N. Vincent, Canterbury and York Society 83 (1996), no.25. |

17 | RLP, 133-3b; RLC, i, 195, and cf. Diary and Itinerary 31 August - 6 September and 30 November - 6 December. |

18 | RLP, 132b, and cf. Diary and Itinerary 8-14 March. |

19 | RLP, 132b-3. |

20 | RLP, 132-2b, and cf. RLP, 133, orders concerning William de Ros, who had fined 30 marks for his release from the prison of John fitz Hugh. For the seal matrix of Ingelram de Préaux, excavated from the Fleet Ditch in London in the 1670s and now in the collections of the Museum of London (accession 45.41), see <http://www.culture24.org.uk/history-and-heritage/art66339>. |

21 | RLP, 133b. |

22 | RLC, i, 194b. |

23 | RLC, i, 194b. |

24 | RLC, i, 195. |

25 | RLC, 194b-5. |

26 | RLC, i, 194b |

27 | RLC, i, 195, and cf. John's charter to the men of Devon, 18 May 1204, RC, 132-132b, as noted Diary and Itinerary 30 November - 6 December. |

28 | RLP, 132b, and cf. Diary and Itinerary 2-8 November. |

29 | RLC, i, 194-4b |

30 | RLC, i, 195. |

31 | For the negotiations here, cf. Diary and Itinerary 22-8 March, and cf. Edmund King, Peterborough Abbey, 1086-1310: A Study in the Land Market (Cambridge, 1973), 83. |

32 | Best preserved in Cambridge, University Library ms. Dean and Chapter of Peterborough 1 (Peterborough cartulary) fos.66v-67r (51v-52r), with various other copies including TNA E 32/76 (Northamptonshire Forest Eyre Roll 5 Edward I) m.3d, and cf. the orders for the charter's enforcement, RLP, 132b; RLC, i, 194b. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)