John writes from La Rochelle, pleading for reinforcements

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

6 July 1214 - 12 July 1214

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

7-8 Jul 1214 |

RC, 200; RLP, 117b-118; RLC, i, 168b |

||

9-12 Jul 1214 |

RC, 200; RLP, 118; RLC, i, 168-169 |

||

12 Jul 1214 |

RLP, 119 |

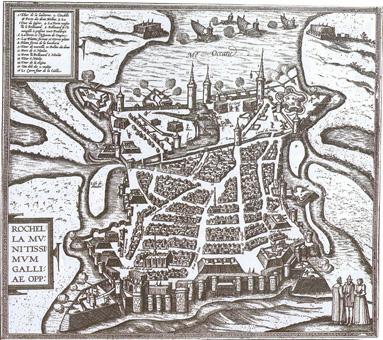

Having abandoned his position on the Loire, John went south to La Rochelle, travelling through a location that was perhaps Pouzauges on Saturday 5 July, certainly pausing at Mauzé-sur-le-Mignon on Monday on Tuesday 7-8 July before reaching La Rochelle on Wednesday 9 July. He can have had little idea at this time that he would never again see Angers or his lands to the north. Nonetheless, in his absence, Louis set about tearing down the walls that John had begun to construct around Angers, and retook the castle of Beaufort-en-Vallée, 30 kilometres further east.1 John's retreat from La Roche-aux-Moins was, in hindsight, to become one of the great turning points of the reign, and in consequence, of English history. In May 1222, founding a new Augustinian abbey of Notre-Dame de la Victoire near Senlis to commemorate his triumphs, Philip Augustus dedicated the new foundation not only to his own victory at Bouvines in late July 1214, but to his son's at La Roche-aux-Moins three and a half weeks earlier.2 According to Matthew Paris, writing in the 1230s, the French took more encouragement from John's defeat at La Roche than from that of his allies at Bouvines, since they now realized that in Louis they had a prince prepared to lead them in battle.3 At the time, however, there is little to suggest the panic or chaos that French chroniclers attribute to the event. There is nothing in the chancery rolls, for example, to suggest the negotiation of ransoms to pay for English knights captured at La Roche-aux-Moins. Only in hindsight did the retreat from the Loire acquire its full significance.

Pausing at Mauzé on 7 July, the King granted a charter of privileges to the men of Dax in the far south of Gascony, renewing their quittance from custom as enjoyed in the time of kings Henry II and Richard I. The charter is significant as much for its witness list as for its contents, revealing the presence at John's court of the bishop of Dax and Arnaud Raimond III, vicomte of Tartas, as well as of other prominent figures from the south.4 For these men to have encountered John in the midst of his flight from the Loire can hardly have helped to steady nerves. On the same day, the men of Saintes were told to be obedient to Hugh de Lusignan in accordance with the terms of the King's earlier peace with the Lusignans: yet further evidence of the compromises that John was forced to make in order to maintain peace in the south.5 From La Rochelle after 9 July, now reunited with his treasure and the rump of his administration, the King issued a great flurry of letters, commanding action in France, England and Ireland. Amidst the routine, and without any mention of the King's recent setbacks, we find letters that speak of John's disquiet. There was continued anxiety, for example, over the Exchequer pensions owing to cardinals and other English representatives in Rome. Amidst negotiations over the vacant bishoprics of Carlisle and Worcester, and with the ever-present threat of rapprochement between the Pope and Philip Augustus, it was essential that diplomatic channels to Rome remain open.6 There were presents for an envoy from the King of Norway, one of King John's chief allies in the north, and a particular command for the best possible gifts of grain, rings and brooches to be made to King Inge himself, 'since he has been so generous in his gift of jewels'.7

Routine instructions to the King's representatives in Gascony and Ireland, commanding the transfer of land, suggest particular caution in respect to local legal custom, promising that the King's courts would uphold the 'right customs of our land of Gascony' (rectas consuetudines terre nostre Wasonie) and respect for 'the custom of Ireland' (secundum consuetudinem terre nostre Hibernie).8 There were also delicate negotiations to be transacted, over the granting of the great Welsh Marcher estate of William fitz Alan to Thomas of Erdington, himself a major figure in John's diplomacy, and over the offer of a widow to Robert de Harcourt, brother of a major Anglo-Norman nobleman pivotal in the continued attempts to woo Normandy away from King Philip. Even here, however, there was a degree of caution. Robert de Harcourt sought marriage with the widow of Guy de Dives, but before this could be granted, the widow was to be asked whether she approved the match.9 What we find here is respect for a widow's own wishes, in many ways in accordance with the future clause 8 of Magna Carta, forbidding the King to marry off widows against their will. Another instruction to England, concerning the fine offered by Roger de Mortimer for various lands in marriage, is scrupulous in forbidding any waste of the land of an heir in custody, again here predicting Magna Carta clause 4.10

Yet however carefully the King trod, these negotiations fit into a context of continued suspicion and double-dealing. Most notably here, on 11 July, the Justiciar (Peter des Roches) was informed of an offer of 15,000 marks made by the English baron Geoffrey de Say for the inheritance of William de Mandeville (d.1189). This was an inheritance that had already, in theory, been assigned to William's kinsman, Geoffrey fitz Peter, and thence to Geoffrey fitz Peter's son, Geoffrey de Mandeville. In July 1214, the Justiciar was asked merely to enquire what might be best to do about Geoffrey de Say's offer.11 Even so, for the King to begin undermining the rights of Geoffrey de Mandeville was a potentially explosive manoeuvre. In due course, both Geoffrey de Mandeville and Geoffrey de Say were to be numbered amongst the leaders of the rebel party at Runnymede.

By far the most evocative letter sent by the King during this week survives on the chancery Patent Roll. Apparently sent from La Rochelle immediately after the King's safe return there on 9 July, it is worth translating in full:

'The King sends greetings to all his earls, barons, knights and other faithful men throughout the realm of England. Know that we are in good health and uninjured, and that the grace and joy of God prosper amongst us. We send repeated thanks to those of you who have dispatched your knights to us to serve in upholding and winning our rights, and we ask most attentively, just as you value our honour, that those of you who have not crossed over with us, come to us without delay to bring assistance to the winning of our land, all save for those who with the counsel of our venerable fathers P(eter) bishop of Winchester, our justiciar, J(ohn) bishop of Norwich, Master Richard Marsh and William Brewer, are to remain behind in England. You should act here so that we are bound in permanent gratitude towards you. Should any of you suspect that we harbour aindignation against hima, through coming to us he bmay repair thisb'12

This opens as a standard royal newsletter, intended to quieten rumour and to assure his subjects of the King's continued prosperity. Reading between the lines however, a number of anxieties emerge. Firstly, there was clearly an unspoken fear that the defeat at La Roche-aux-Moins might now breed panic. Secondly, there was concern, and even anger ('rancour/indignation') that large numbers of English barons had failed to send service to the King in Poitou. The redrafting of the final clauses of this letter (where 'rancour of soul' has been transformed into 'indignation', and complete remission into a mere possibility of forgiveness), all suggest less than confident dealing between King and barons. As early as May 1214, the King's clerks had begun to compile lists of English landholders serving in Poitou, in order to establish who did and who did not still owe the scutage (or 'shield money' for knights) owing from those who did not render military service in person. This 'scutage of Poitou' was charged at the relatively high rate of 3 marks per knight's fee. The list of service, copied onto the back of the chancery Close Roll in May (regularly updated thereafter, through to the end of August), reveals that a large number of barons did indeed serve with the King. Amongst the twenty-five barons specifically named in Magna Carta as leaders of the opposition, for example, at least six either served in Poitou in person or sent knights to represent them: William de Lanvallay, William of Huntingfield, Richard de Montfiquet and Geoffrey de Say apparently in person; Saher de Quincy earl of Winchester, via his son, and Roger Bigod earl of Norfolk, who sent knights.13 It was almost certainly because they had too close, rather than too warped, an experience of John's personal leadership that such men became increasingly critical of the King. Even so, taken in conjunction with the evidence of the Exchequer Pipe Roll, what the list of scutages reveals is that large numbers of barons not only failed to turn out in person (a decision apparently taken by no less than 19 of the 25 barons of Magna Carta) but refused to pay scutage on the fees for which they were in theory liable.14 In the aftermath of his defeat at La Roche-aux-Moins, the King might boast of prosperity, grace and joy. In reality, his situation was increasingly perilous.

a'rancour in our soul' crossed out b'will have such rancour entirely remitted' crossed out

1 | C. Petit-Dutaillis, Étude sur la vie et le règne de Louis VIII (1187-1226) (Paris 1894), 51. |

2 | Petit-Dutaillis, Louis VIII, 52. |

3 | Matthaei Parisiensis Historia Anglorum, ed. F.Madden, 3 vols. (London 1866-69), ii, 150. |

4 | RC, 199b-200, also in an inspeximus by Henry III, 3 August 1237, itself recited 1294, in Le Livre noir et les établissements de Dax, ed. F. Abbadie (Bordeaux 1902), 243-5. |

5 | RLP, 117b, and for the settlement with the Lusignans agreed in late May, Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 123, 125. |

6 | RLP, 118 (including orders for pensions to Peter Saracen and to cardinal Guy Pierleoni, here described as the King's kinsman, perhaps by an otherwise obscure Italian alliance on behalf of one of King John's maternal ancestors); RLC, i, 168 (governing pensions of the bishop of Ostia and cardinals Guala and John de Columna). For instructions over Worcester and Carlisle, see RLP, 118; RLC, i, 168. |

7 | RLP, 118b; RLC, i, 168 (nos de iocalibus suis copiose visitauit). |

8 | RLP, 118b; RLC, i, 168. |

9 | For the Fitz Alan marriage, RLP, 118b. For Robert and William de Harcourt, RLC, i, 168, requesting enquiry de voluntate uxoris predicti. |

10 | RLC, i, 168: tunc non permittatis wastum fieri inde quod de custodia non pertinet faciendum, et si iam wastum inde factum fuerit quod fieri non debeat, id sine dilatione emendari. |

11 | RLC, i, 168. |

12 | RLP, 118b. |

13 | RLC, i, 200b-201b, copied onto the back of a membrane that otherwise records letters issued between 8 May and 6 June, with notations showing updating on 3 and 7 June and 20 and 29 August. |

14 | For the 'scutage of Poitou', the principal authority remains J.C. Holt, The Northerners: A Study in the Reign of King John, 2nd edn. (Oxford, 1992), and Holt's contribution to the Pipe Roll 17 John. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)