King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

30 Nov 1214 |

RLC, i, 179b |

||

2 Dec 1214 |

RLP, 124b, 140b; RLC, i, 180b |

||

3-4 Dec 1214 |

RLP, 124b; RLC, i, 180b |

||

4 Dec 1214 |

RLP, 130b |

Hardy ('Itinerary') places the King at Sturminster on 3 December, source unidentified. |

|

6-8 Dec 1214 |

RLP, 125; RLC, i, 180b, 181 |

This week spanned the period between Advent Sunday (30 November) and the feast of St Nicholas (6 December), both of them important occasions in the royal liturgical year. As winter set in, it became more difficult for the court and its vast apparatus of carts, hounds, clerks, chaplains and cooks to traverse the roads of England, themselves unimproved since the time of the Romans. But for the hyperactive King John, even winter weather seems to have done little to halt the court's frenetic itinerary. In the present week, the King travelled from Ludgershall twenty kilometres to Clarendon in Wiltshire, then a further sixty kilometres south to Corfe Castle in Dorset. On the Thursday, he left Corfe to travel seventeen kilometres to Sturminster (probably William Marshal's manor of Sturminster Marshall rather than nearby Sturminster Newton), and then on Friday or Saturday a further thirty kilometres to Gillingham north of Shaftesbury. In all, he travelled at least 127 kilometres or 80 miles in six days.

As early as 2 December, the King had decided to spend Christmas at Worcester. Instructions were dispatched to the reeves of Wilton to buy cloth for the King's table, and to the monks of Reading to bring the King's silver vessels and plate from Reading to Worcester, and there wait until it could be returned to safe keeping at Reading.1 Since 1154 and the accession of the Plantagenet dynasty, no King had spent Christmas at Worcester. John had passed previous Christmases at nine other places in England, showing a marked preference for Windsor (1207, 1209, 1211, 1213). Here, he followed in the footsteps of his father, Henry II, who had spent Christmas at Windsor both in 1175 and 1184. Worcester was in general a location that kings visited only in the spring or summer, on expeditions against the Welsh. John had only once before been there in winter, very briefly in January 1206. To judge from his itinerary in December 1214, Worcester was chosen for its convenience for contacts with the Welsh, to be established in the week before Christmas, at Monmouth and in Herefordshire. This in itself is revealing since it suggests that as early as December 1214, the King's thoughts had turned to the possibility of trouble on the Marches.

On 3 December, from Corfe, John instructed Thierry Teutonicus (whom we last encountered on 30 October) to take Queen Isabella to Gloucester, and to 'keep' her there in the bed chamber where the King's daughter, Joan, was nursed.2 The four year-old Joan, born in July 1210, had earlier that year been taken to Poitou and entrusted to her intended husband, Hugh X de Lusignan (the son of Queen Isabella's late fiancé, Hugh IX de Lusignan, himself jilted in 1200 so that Isabella could marry King John). Isabella's memories of Gloucester were perhaps tinged with nostalgia for the latest of her offspring. The King probably met her at Gloucester, when he passed through later that month. The concern shown for Isabella's safe-keeping may once again speak of a growing fear of civil unrest. Alternatively, there may have been more personal considerations. In 1214, Isabella was pregnant, in due course giving birth to a daughter, Isabella, much later married to the German emperor, Frederick II. The birth is reported to have taken place in 1214 at Gloucester. If so, it presumably occurred in December rather than before the Queen and King's crossing to Poitou in February.3 In these circumstances, the King's concern for his wife's well-being may bear a rather less sinister interpretation than has previously been allowed.

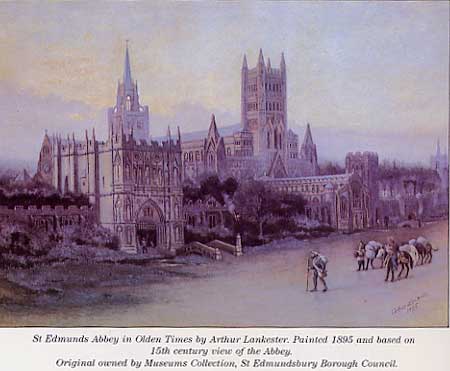

The most interesting of the business recorded this week concerned the Church. On 21 November, the King had promised that 'elections are to be free in perpetuity in every and each cathedral or conventual church or monastery'. Less than a fortnight later, the precise meaning of these words became apparent. From Clarendon, on 2 December, the King wrote to the papal judges delegate appointed to resolve the continuing deadlock at Bury St Edmunds, notifying him that he was too preoccupied with difficult business (Quoniam arduis prepediti negociis) to attend the hearing arranged for the following week, but that he would instead send Henry de Vere to serve as his proctor.4 There was certainly no question here of the King backing down or accepting the monks' own elected candidate, Hugh of Northwold. On the same day, and no doubt with deliberate intent, the monks of Bury were sent one of the letters that the King had been dispatching since 21 November, asking that they graciously agree to abandon all claim to 'ablata' taken from them during the Interdict, in return for the King's future good will.5 A blank form, allowing for just such a quitclaim, was copied onto the dorse of the chancery Patent Roll.6 In all likelihood, this was part of a wider campaign, led by the chancellor Richard Marsh, who is said to have travelled the country with just such blank charters demanding the abandonment of legitimate claims. Marsh was certainly in East Anglia by this time, involved in ongoing negotiations over the vacancy receipts from the bishopric of Norwich where, on 2 December the Norwich monk, Master Ranulf of Warham, was reappointed as custodian of the vacant see.7

According to the chronicler of the Bury election, Marsh delivered the King's letters at Bury on 9 December, when he came there in company with the King's proctor, Henry de Vere, and the bishop of Worcester, Walter de Gray, Marsh's predecessor as royal chancellor. A powerful group of monks, headed by the prior and sacrist, was prepared to issue the quitclaim demanded. They and Marsh described any who opposed such letters as 'disturbers of the King's peace' (regie pacis perturbatores), 'opposers of the King's will' (eiusque voluntati repugnantes), or even as 'the King's enemies' (inimici regis).8 The minority, however, drawn from supporters of the abbot elect, demanded a respite of two weeks, and meanwhile placed the abbey's seal under appeal to the Pope, so that no letters could be sealed pending a decision by papal judges. One of the monks, Ralph of London, openly accused Marsh of extorting a ruby ring that hung around the chancellor's neck.9 The opposition party then consulted the bishop of Ely, who urged them to remain steadfast. When Marsh and his fellow proctors returned to Bury on 21 December to discuss both the disputed abbatial election and the King's demand for a quitclaim of damages, the controversy continued. The prior and various others sealed letters under their own seals, offering the quitclaim demanded by Marsh and the King. But the abbot-elect's party, unbowed, still demanded 4000 marks calculated in damages inflicted by the King and refused to allow the convent's seal to be used.10

Meanwhile, on 4 December, from Corfe, the King sent instructions to a series of monastic houses concerning the election of new heads. The monks of Battle, and the canons of Darley and Grimsby were all instructed to proceed to elections, but with the specific proviso that they were to listen to the demand of the King's proctors, Philip Mark at Darley, William Brewer at Battle, and the sheriff of Lincolnshire at Grimsby. Having elected abbots, they were then to send them to court as abbots-elect with other representatives, for the King's assent.11 All of this was in accordance with the letter, but hardly with the spirit of the charter of free elections issued a fortnight previously. In particular, the appointment of heavy-weight enforcers such as Marsh, Grey and Henry de Vere at Bury, William Brewer or Philip Mark at Battle and Darley was an indication of the King's continued determination to control electoral process. The fact that at Darley, Henry of Repton seems to have been serving as abbot elect for some months or years before this, being recognized as such by the King only on 21 December 1214, suggests that, as at Bury St Edmunds, there may have been a lengthy stand-off between monastic and royal interests.12 Even more alarming were royal letters sent to the prioress and convent of Barking. Following the death of the late abbess of Barking, there had been attempts by the King to secure a successor, and above all to prevent the election of a sister of the future rebel leader, Robert fitz Walter.13 The King now requested that the nuns elect Sarah of Walbrook, a member of their own community, 'in so far as you wish to preserve and maintain your liberties elsewhere'.14 This was not only to demand that a particular candidate be elected but raised a crudely veiled threat should the nuns disobey instruction.

It is surely of significance for the King's crumbling authority that the nuns seem to have ignored his instructions. Certainly, there is no evidence that Sarah was elected abbess, an office that seems to have remained vacant until September 1215, when the King at last approved the election of Mabilia of Bosham.15 For the difficulties posed to electors at this time, we can also turn to an extended account of events at Rochester, where the monks, having been placed under the patronage of Archbishop Langton, were now obliged to elect a candidate pleasing to both King and archbishop. If they failed to follow the archbishop's bidding, they feared a change in their status (presumably, that they would be treated in future not as an episcopal church but as a mere satellite of Canterbury). On 13 December, they met with Langton and his brother, Master Simon, in the Chapter House at Rochester. Having agreed to elect, the monks now sought permission to retire. Instead, in a fine display of magnanimity intended to emphasize the canonical regularity of proceedings, Stephen and Simon withdrew from the Chapter House. The monks duly elected Benedict of Sawston, Langton's former pupil: a candidate who, far from being persona grata with the King, was still at this time teaching in the schools of Paris. News of his promotion had to be sent to Benedict in France, from where he travelled to be consecrated at Osney, near Oxford, in January or February 1215.16

Throughout the period following the King's return from Poitou, and with the exception of the orders of late November for the prosecution of heresy in Gascony, there is a remarkable absence of business from the chancery rolls concerning John's lands in France. In the present week, there were two minor exceptions: a command that a piebald horse and its (presumably valuable) harness, received from Hugh de Lusignan, be granted to William de Harcourt, and presentation for Philip dean of Poitiers as rector of Wearmouth, in the vacant bishopric of Durham.17 For the rest, we are left to speculate that the majority of letters concerning Gascony, Poitou and in all probability Ireland, were either never enrolled or were entered in chancery rolls now lost to us.

Finally, on or around 6 December, instructions were sent out to summon twelve knights from the counties of Somerset, Devon and Cornwall to meet with the King on 1 January.18 The intention was to discuss an offer made to Hugh de Neville in his latest perambulation of the royal forest. The men of the west had long since fined communally for liberties. In 1203-4, for example, there had been communal offers of 5000 marks from Devon for a charter disafforesting all of the county save for Dartmoor and Exmoor, and a fine of 2200 from the men of Cornwall to be quit of all forest pleas and to have election of one of their own to be presented to the King for appointment.19 More recently, in 1208, the men of Cornwall had offered a further 500 marks to choose their own sheriff, and 200 marks for the King to end his 'malevolence' towards them. Pending payment of the 200 marks, King John gave them the royal chamberlain, Geoffrey de Neville, as sheriff.20 1209-10, the men of Dorset and Somerset had offered 1200 marks to be quit of an amercement of 100 marks previously charged on the county farm and to have a sheriff chosen by the King from amongst those living in the county, specifically excluding the nomination of William Brewer or his associates.21 The renewed discussion of such offers in December 1214 suggests not only that the county communities remained active in the pursuit of local interest (itself a feature of no small importance to the emergence of Magna Carta) but that, in the winter of 1214, they were fears that the King would renege upon privileges purchased more than a decade earlier. These were unsettled times.

1 | RLC, i, 180b. |

2 | RLP, 124b, and see the corresponding notification to the sheriff of Gloucestershire, RLC, i, 180b. |

3 | I can find no certain authority for the place or date of Isabella's birth, although Gloucester 1214 is reported in the secondary literature, as is the birth of Eleanor, the last of John 's daughters, again attributed to Gloucester, in 1215. The ODNB entries on Eleanor and Isabella (by Elizabeth Hallam and David Abulafia) are rightly cautious in supplying neither a certain date nor place of birth. |

4 | RLP, 124b. |

5 | RLP, 140b. |

6 | RLP, 140b-141. |

7 | RLP, 124b; RLC, i, 180b. |

8 | The Chronicle of the Election of Hugh Abbot of Bury St Edmunds and Later Bishop of Ely, ed. R.M. Thomson (Oxford, 1974), 134-6. |

9 | Ibid. 136-8. |

10 | Ibid., 138-47. |

11 | RLC, i, 180b-181, all of 4 December, also recording letters of 3 December informing Brewer that he would be approached by monks of Battle and that he should speak with them over their election, salua dignitate nostra prouidentes. |

12 | See D.M. Smith and V.C.M. London, The Heads of Religious Houses. England and Wales II: 1216-1377 (Cambridge, 2001), 373. For Battle, where the monk Richard was eventually granted royal assent on 22 January, see Ibid., 22. |

13 | RLC, i, 202 |

14 | RLC, i, 180b. |

15 | RLC, i, 227b, and cf. Smith and London, Heads of Houses, 541. The account of these events in VCH Essex, ii, 116, 121-2, is not reliable. |

16 | H. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, 2 vols. (London 1691), i, 385-6, an account of proceedings as preserved in the register of Archbishop Islip (1349-66), supplying 25 January as the date of Benedict's consecration, with the alternative date 22 February noted in John Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae, 1066-1300, ed. D. E. Greenway (London, 1968 - ), ii, 76, and in the itinerary attached to K. Major, Acta Stephani Langton, Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi, A.D. 1207-1228 (Canterbury and York Society, 1950), 164-5, this latter failing to note Langton's presence either at Rochester on 13 December or slightly earlier at Halling, as reported by Wharton. |

17 | RLP, 130b (not enrolled until March 1215); RLC, i, 180b. |

18 | RLC, i, 181. |

19 | Pipe Roll 6 John, 40, 85, and for the offer by the men of Cornwall, see the account by W.A. Morris, The Medieval English Sheriff to 1300 (Manchester, 1927), 182-3, fleshing out the offer recorded in the Pipe Roll. For the charter granted on this occasion to the men of Devon, see RC, 132-132b, with a better copy preserved in Dublin, Trinity College ms. 524 (Torre cartulary) fo.28r-v, dated 18 May 1204. |

20 | Rot.Ob., 434. |

21 | Pipe Roll 12 John, 75. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)