Magna Carta and Peace

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

14 June 1215 - 20 June 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

10-14 Jun 1215 |

RLP, 142b-3; RLC, i, 214b; Chronicle of the Election of Hugh, 170-3 |

||

15 Jun 1215 |

Magna Carta |

||

16-18 Jun 1215 |

RLP, 143-3b; RLC, 214b-15b; Rot.Ob., 551 |

||

18 Jun 1215 |

RLP, 143b |

||

19 Jun 1215 |

RLC, i, 215 |

||

19-20 Jun 1215 |

RC, 210-10b; RLP, 143b, 180b |

Magna Carta was sealed at Runnymede on Monday 15 June, the morrow of Trinity Sunday. On Trinity Sunday itself the King was at Windsor. It was at Windsor that we can assume him to have stayed overnight throughout the following week, making his way, day by day, from Windsor to Runnymede for negotiations with the rebels, certainly on Monday 15th, and again on Thursday, Friday and Saturday 18-20th June. Ralph of Coggeshall, the only one of the chroniclers to supply such details, refers specifically to the fact that the barons came to Runnymede fully armed, and that both they and the King pitched tents in the meadow.1 This is not the place to enter into the finer details of the settlement devised on 15 June, a task already performed with distinction by such authorities as J.C. Holt and David Carpenter. It is nonetheless worth pointing out one significant misunderstanding that since the 1950s has beset those who have written on the dating and implementation of the great charter. Following the lead of Holt and of C.R. Cheney, a great number of words have been wasted in attempts to reassess the dating clause of Magna Carta ('At the meadow called Runnymede between Windsor and Staines, 15 June (1215)'). This has been done on the grounds that subsequent royal letters, of 19 and 20 June state that peace was not properly made between King and barons, nor homages retaken, until Friday 19 June. In the interim, critics (beginning with Holt and Cheney) have asked, how could Magna Carta itself have been issued on 15 June, as if peace had already been made and King and barons were in a position to agree terms?2

What is at stake here is a failure to grasp the realities of medieval diplomatic as applied to the making to peace treaties. Magna Carta was, in essence, merely one amongst many surviving treaties. The very terms of its dating clause ('at the meadow named Runnymede between Windsor and Staines') is standard for a peace treaty (generally issued in liminal locations, 'at X between X and Z'). Key to the understanding of any such treaty, we must bear in mind that terms had first to be agreed and set out in writing before they could, in due course, be implemented. Most recently, this had been precisely what had happened in September 1214, when the kings of France and England had made their truce, King Philip dating his side of the bargain at Chinon on 18 September, King John his at Parthenay also on 18 September. In this particular instance, negotiations beforehand had ensured that both parties could seal their side of the agreement confident that the truce itself would run from the day of sealing. At Runnymede, just under a year later, the King issued a charter promising terms, on Monday 15 June. This was followed by four further days of discussion amongst the barons as to whether to accept these terms, ended on Friday 19 June when the rebel barons returned to the King's allegiance and the King received the barons' homage ('eorum homagia eodem die ibidem cepimus').3 As we have seen, although prepared to admit that the period from early May to 19 June had been one of open war, the King seems himself never formally to have repudiated the homages that the barons themselves had thrown off on 3 May. As a result there was nothing either inherently or practically incorrect in the form of the charter that he issued on Monday 15 June. As a result, there is no further need for the sort of anguished uncertainty over Magna Carta's date that Holt and others have encouraged.

At the same time, one other feature of the dating here has a significance that Holt and others have overlooked. Magna Carta was issued on the Monday (a day, as Sidney Painter and more recently Hugh Doherty have reminded us, traditionally set aside for tournaments) after Trinity Sunday.4 Trinity Sunday itself was a feast day with particular resonance for those in attendance in 1215. It had been on Trinity Sunday, 3 June 1162, that Thomas Becket had been consecrated as archbishop of Canterbury, immediately declaring this to be a feast for general observance throughout England.5 Almost certainly out of deliberate respect for the memory of St Thomas, Stephen Langton had waited for several weeks following his election as archbishop of Canterbury, in order that he might receive consecration at the hands of Pope Innocent III, at Viterbo on 17 June (Trinity Sunday) 1207.6 Moreover, and here going beyond Langton's particular devotion to the feast of the Trinity, to the specific consequences of such devotion, it is worth remarking that the Trinity Sunday liturgy involved the recital of Revelation 4:1-11, a text that describes the throne of God surrounded by twenty-four elders. I have suggested elsewhere that the coincidence here may be yet another indication that it was under guidance from Langton that King and barons came to decide upon the number twenty-five for the committee of baronial guarantors first mentioned on 15 June 1215, the morrow of Trinity Sunday.7

As for the rest of this week's business, on Tuesday 16 June, the King wrote to Marlborough to demand 600 marks in cash, followed shortly afterwards by a request that 200lbs of wax be sent from Winchester to Odiham.8 Magna Carta included Scottish and Welsh business. With the archbishop of Dublin in attendance at Runnymede, there were also negotiations with Ireland. On 16 June, the King offered promotion to one of the archbishop's clerks and commanded the release of William de Cusack, whose terms for release had been under discussion since at least 1213 and were finalized in June 1215 with an offer of 100 marks.9 A large volume of Irish fines are recorded on the Fine Roll at this time.10 On the same day, 16 June, orders were sent to the sheriff of Gloucestershire for the restoration to land seized from Roland Bloet in Gloucestershire that may represent the first in what was soon to become a spate of restorations to former rebels.11 On Wednesday 17 June, four Wiltshire knights were appointed as de facto justices in the county to ensure proper hearing of a case of homicide delayed for the past few years. These four men were to act independently of the local sheriff who was nonetheless commanded to attend their meeting, in arrangements that, as with the wider enforcement of terms between King and rebels, perhaps suggest a reluctance to rely too heavily upon shrieval administration of cases where justice had to be seen to be done.12

On 18 June, again in a move that seems appropriate given the extent to which Magna Carta had insisted upon the right custody of widows and daughters, the King intervened to command the restoration of her brother's inheritance to the wife of Aimery vicomte of Thouars, previously disputed with her niece, herself a niece of Savaric de Mauléon.13 On the same day, he assented to the election of Iorweth abbot of Talley as bishop of St David's, commanding Archbishop Langton to confirm this choice.14 Iorweth, consecrated by Langton at Staines on 21 June, seems to have been a candidate forced upon the King by Llewelyn and the Welsh princes.15 At the same time, the King wrote to the chapter of York authorizing them to proceed to the election of an archbishop provided that they act in accordance with previously received written instructions from the Pope.16

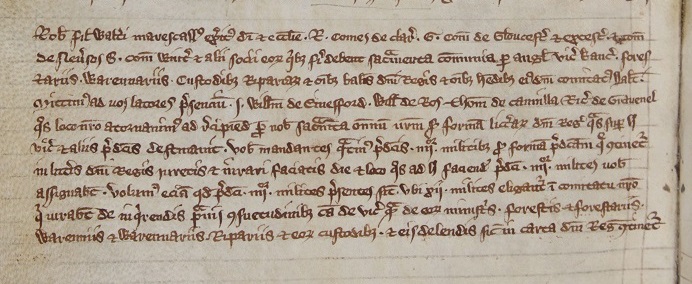

It was at about this time, on Thursday 18 June, that formal agreement was reached that the firm peace between King and barons should be deemed to run from the following day, Friday 19 June. Certainly, on 18 June, from Runnymede, the King sent letters to the royalist Stephen Harengod, and one assumes to a great many others, commanding the cessation of all hostilities directed against the rebels. No further fines or 'tenseria' were to be levied from rebel lands, and all prisoners or hostages taken in the late war ('occasione huius guerre') were to be released.17 On Friday itself, 19 June, letters were sent to sheriffs and other royal officers throughout England announcing the peace, made 'by God's grace', and commanding its implementation. In accordance with the securities clause of Magna Carta, arrangements were made for oaths to be sworn in each county to abide by the judgement of the twenty-five barons appointed by Magna Carta as arbiters of peace. At the same time, to ensure implementation of clause 48 of the charter, it was agreed that twelve knights be elected in each county to enquire into and suppress the misdeeds of sheriffs, foresters, warreners and the keepers of river banks.

Only a general form of these 'letters of peace' survives, copied on to the dorse of the Patent Roll with date at Runnymede on 19 June.18 An original, in identical terms but specifically addressed to the county of Gloucestershire, survives still in Hereford Cathedral, dated at Runnymede on Saturday 20 June.19 As argued by its editor, Ifor Rowlands, this is almost certainly one of the 'pair of letters patent' that the King commanded ordered to be sent to Engelard de Cigogné, sheriff of Gloucestershire, itself recorded in a memorandum of the dispatch of this and other such letters, including orders for similar 'pairs' of letters to be sent to Yorkshire (via Philip fitz John), Worcestershire (via the bishop of Worcester), Dorset and Somerset (via a clerk of the bishop of Bath), London (via the mayor and sheriffs), Gloucestershire (via Engelard), Leicestershire and Warwickshire (via the earl of Winchester), Northumberland (via Eustace de Vescy), Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Lancashire, Cumberland, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, Essex, Cornwall, Kent (all twelve counties via the royal clerk, Henry de Vere). Similar pairs of letters were issued on 24 June (the feast of St John the Baptist) for the counties of Oxfordshire and Bedfordshire (via the bishop of Lincoln), and subsequently for Rutlandshire, the Cinque Ports, Berkshire, Staffordshire, Sussex, Devon, Northamptonshire, Surrey, Hampshire, Shropshire, Westmoreland and Buckinghamshire (these last all being delivered by Master Elias of Dereham, steward of archbishop Langton).20 The same publication schedule that refers to the dispatch of these 'pairs' of letters patent (in the case of the counties covered by Elias of Dereham described not as letters patent but as 'writs'), also refers to a total of thirteen 'charters' (by which we can assume Magna Cartas), two sent on 24 June to the bishop of Lincoln, one to the bishop of Worcester, four to Master Elias of Dereham on or after 24 June, and thereafter, at Oxford on Wednesday 22 July (the feast of St Mary Magdalene) a further six for Master Elias.

The distribution of these letters and charters has long been a topic of discussion, the latest theory being that the thirteen Magna Cartas listed in our schedule were each intended for a cathedral church, perhaps one for each of the cathedrals that in June 1215 had a resident bishop.21 In all of this, much less attention has been paid to the description of the letters patent, distributed to the Cinque Ports, London and every English county save Durham, but in virtually all cases described not simply as 'letters patent' but as 'pairs of letters' ('par litterarum patentium').22 An explanation here has recently come to light with the discovery, at Lambeth Palace, of letters issued in the name of five of the twenty-five barons, in this instance specifically directed to the county of Kent, attorning four named knights within the county both to administer the oath to the twenty-five and to ensure the election of the twelve knights set to enquire into and suppress evil customs. My suggestion would be that each 'pair' of letters referred to in the publication schedule comprised one letter in accordance with the form recorded in the name of the King, paired off against another, as in the Lambeth example, in the name of the twenty-five. Each of these baronial letters presumably specified a group of knights named within each county entrusted with the enforcement of oaths and the putting down of evil customs. In other words, this was an operation that not only involved the twenty-five barons in naming knights for each county deemed reliable in the charter's enforcement, but a full-scale system of dual control in which the twenty-five barons took direct responsibility, alongside the King, for administration within the counties.

Matthew Paris, on no very certain authority, supplies a list of 38 barons and knights from the royalist side who served as 'observers and obeyors' ('obsecutores et obseruatores') swearing obedience to the command of the twenty-five.23 Following Roger of Wendover, he also preserves a variant form of the final, securities clause of Magna Carta, perhaps taken from a draft form discussed at Runnymede, according to which the constables of Northampton, Kenilworth, Nottingham and Scarborough were specifically obliged to swear to obey whatever commands the twenty-five barons might issue in respect to these castles.24 Ralph of Coggeshall reports that oaths were sworn, in accordance with the King's letters patent, both to uphold the charter and to pursue hostilities ('infestare') anyone, even including the King, who might oppose it.25

It was almost certainly on the same occasion that the barons, acting in concert, issued their charter to the King over the keeping of London. Claiming to act in the name of the 'earls, barons and other free men of the whole realm', a majority of the twenty-five agreed to hold London 'from the bailiwick ('de ballio')' of the King to 15 August (the feast of the Assumption), the King meanwhile receiving any farms, rents or debts owing from the city. In the same way, the archbishop of Canterbury was to hold the Tower of London, saving the liberties and free customs of the city, and saving whatever oaths had been made for the safe keeping of the Tower. In the meantime, the King was to place no garrison ('munitio') or other men in either city or Tower. Oaths were to be sworn throughout England to the twenty-five barons 'as set out in the charter of liberties and the security granted to the realm'. Before 15 August, the King would restore whatever he had offered to restore or was judged by a majority of the twenty-five due to be restored. If all this were done, then the city and Tower would be returned to the King, saving the liberties and free customs of the city. If the King should fail to keep these terms, then city and Tower would remain to the barons and the archbishop until such time as the terms were fulfilled. Meanwhile, all on both sides were to recover castles, lands and vills which they had held 'at the start of the war begun between King and barons' ('in initio guerre orte inter dominum regem et barones'), the phrasing here once again making it plain that it was generally accepted that from May until 19 June England had existed in a state of open warfare.26

As I have noted elsewhere, the fact that this same treaty refers to the 'letters over the election of twelve knights to suppress evil customs', clearly identical with the 'pairs' of royal and baronial letters noticed above, from 19 June, helps confirm that the London Treaty does indeed date from the same occasion, c.19/20 June. What is otherwise most remarkable about the Treaty, as about Magna Carta, as indeed about the whole tenor of negotiations in early June, is the way in which the King was hereby bound to concessions framed in the most rigid terms, with the barons bound by no such strictures. Some might read this as evidence of King John's fatal propensity to avoid direct conflict. Others, more aware of political reality, might see here evidence that the King had no real commitment to reform. Whilst going through the requisite motions, he made it tacitly yet abundantly clear that this was a settlement forced upon him under duress. Beyond the securities clause of Magna Carta, the barons allowed virtually no mention of physical force to intrude upon terms supposedly negotiated between two willing parties. Even so, and even without the securities clause, it would have been apparent to any outsider, most significantly to the Pope, that this was in reality a forced contract compelling the King into actions that he would not, as a free agent, have considered. Compulsion being foreign to the very idea of mutual consent, this was to expose the entire settlement of June 1215 as a false contract entered into under duress. In much this same way, in 1164, Thomas Becket had succeeded in wriggling out of his commitment to the Constitutions of Clarendon forced upon him by King John's father. In 1215, so it would seem, it was not just Stephen Langton but King John who learned lessons first taught by Becket fifty years before.

On the same day, Friday 19 June, that saw the making of peace and the distribution of letters patent announcing this fact, the King also embarked upon a series of specific acts of restoration intended to answer the grievances of particular barons. In this way, orders were given for hostages to be restored to Roald fitz Alan, constable of Richmond, and to John de Lacy, constable of Chester.27 York castle was to be handed over to William de Mowbray pending the outcome of an inquest into his claim to serve as its hereditary constable.28 At the same time, the earl of Salisbury was informed that the peace, involving the King's restoration of all lands, castles and rights seized by him unjustly and without judgement, would necessarily involve the earl's own claims to the honour of Trowbridge in Wiltshire, previously advanced against those of Henry de Bohun, earl of Hereford. Henry de Bohun had refused any demand for respite in respect to the general lands of his estate, which the earl of Salisbury was commanded immediately to restore. The castle of Trowbridge, however, was excepted from this order, with respite here being granted to Sunday 28 June.29

In the meantime, on Saturday 20 June, the King issued his only charter other than Magna Carta recorded this week. Dated at Runnymede, it takes the form of a quittance for Philip fitz John from suits to hundred or wapentakes and from various other administrative offices. What is interesting here is not only the beneficiary (the same Philip fitz John charged two days earlier with publication of the peace within the county of York), but the witness list. Here we find Archbishop Langton and the bishops of London, Bath and Worcester, and the earls of Pembroke and Warenne, all of them in theory either neutral or supporters of the King, appearing alongside quite another group of men: R(ichard) de Clare, earl of Hertford, William de Mowbray, Eustace de Vescy and Roger de Montbegon (all members of the baronial twenty-five), Robert Grelley and Gilbert de Ghent (former rebels).30 According to the Crowland chronicler and in order to cement their recently made peace, King and barons not only exchanged the kiss of peace and renewed homage and fealty at Runnymede but then dined together.31 In much the same way, a few weeks earlier, following his reconciliation with abbot Hugh of Bury St Edmunds, the King had summoned Hugh to dine with him at Windsor.32 All of these meetings, one suspects, were tense occasions. Whether, despite such tensions, peace could be achieved remained for the moment unsure.

1 | Radulphi de Coggeshall Chronicon Anglicanum, ed. J. Stevenson (Rolls ser., 1875), 172. |

2 | J.C. Holt, Magna Carta (2nd edn., Cambridge, 1992), 248-52, 429-32. |

3 | RLP, 143, and for Friday 19 June as the term to which it was considered legitimate for the King's officers to seize war-time 'tenserii', see orders to William de Cantiloupe of 21 June: RLC, i, 215. |

4 | S. Painter, 'Monday as a Date for Tournaments in England', Modern Language Notes, xlviii (1933), 82-3, reprinted in Painter, Feudalism and Liberty (Baltimore 1961), 105-6, thence taken up in a forthcoming piece by Hugh Doherty. |

5 | Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, iii, 36, 188-189 |

6 | As noted by N. Vincent, 'Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury', Etienne Langton: prédicateur, bibliste, théologien, ed. L.-J. Bataillon, N. Beriou, G. Dahan and R. Quinto (Turnhout 2010), 82. |

7 | Vincent, 'The Twenty-Five Barons of Magna Carta: An Augustinian Echo?', Rulership and Rebellion in the Anglo-Norman World, c.1066-c.1216: Essays in Honour of Professor Edmund King, ed. P. Dalton and D. Luscombe (Farnham, 2015), 231-51, esp. pp.247-8. |

8 | RLP, 143; RLC, i, 214b. |

9 | RLP, 143, and for William de Cusack, see Rot.Ob., 479, 551; RLC, i, 174b, 228b, 241 (CDI, nos 497, 520, 559, 562). On the same day, 16 June, Matthew fitz Herbert, William's gaolor, was promised the restoration of possessions taken from him and his men in Wiltshire: RLC, i, 214b. |

10 | Rot.Ob., 551-3. |

11 | RLC, i, 214b. |

12 | RLC, i, 214b. |

13 | RLP, 143b. |

14 | RLP, 143. |

15 | St David's Episcopal Acta 1085-1280, ed. Julia Barrow, South Wales Record Society xiii (1998), 10-11; J. Beverley Smith, 'Magna Carta and the Charters of the Welsh Princes', English Historical Review, xcix (1984), 357-8, noting that bishop Iorweth was consecrated at Staines on 21 June in company with another native Welshman, the newly elected bishop of Bangor. |

16 | RLP, 143b, and cf. RLC, i, 215b for payment of the expenses of the prior of St Oswald Nostell and Master Robert of Winchester, sent on the chapter's behalf, to request the King's licence. The papal letters referred to seem to be lost. |

17 | RLP, 143b, whence Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 493 no.5, with discussion of the dating here by Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 253 and note. |

18 | RLP, 180b, whence Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 493-4 no.6. |

19 | Hereford Cathedral Archives charter no.2256. |

20 | Ifor Rowlands, 'The Text and Distribution of the Writ for the Publication of Magna Carta, 1215', English Historical Review, cxxiv (2009), 1422-31, citing the publication schedule from the dorse of the patent roll, whence RLP, 180b. |

21 | Rowlands, 'Text and Distribution', 1428, thence taken up by David Carpenter, Magna Carta (1215), 375-7. Episcopal distribution of the charter is also implied by the Dunstable annalist: Annales Monastici, ed. Luard, iii, 43 ('confecte sunt ibidem charte super libertatibus regni Anglie, et per singulos episcopatus in locis tutis deposite'). Ralph of Coggeshall suggests a county-by-county distribution: Coggeshall, 172 ('Mox igitur forma pacis in charta est comprehensa, ita quod singuli comitatus totius Anglie singulas unius tenoris haberent chartas regio sigillo communitas'). The Crowland chronicler refers to its display in towns and other places: Walter of Coventry, ed. Stubbs, ii, 222 ('Deferebatur interim exemplar illius carte per ciuitates et vicos, et iuratum est ab omnibus quod eam obseruerent, ipso rege hoc iubente'). |

22 | RLP, 180b. |

23 | Matthaei Parisiensis , Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard, 7 vols. (Rolls Ser., 1872–83), ii, 605-6, 'Obsecutores et obseruatores ... isti omnes iurauerunt quod obsequerentur mandato viginti quinque |

24 | Wendover, in Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. Luard, ii, 603: 'Et ad melius distringendum nos, quatuor castellani, de Norhantun scilicet, de Kenillewurthe, de Nithingham, et de Scardeburc, erunt iurati [predictis] viginti quinque baronibus quod facient de castris predictis quod ipsi preceperint et mandauerint, vel maior pars eorum. Et tales semper castellani ponantur in illis castris qui fideles sint et nolint transgredi iuramentum suum'. |

25 | Coggeshall, 172-3: 'Inde tirocinia diuersis in locis Anglie barones exercuerunt. Fit generalis iuratio a singulis tam militibus quam liberis hominibus per singulos comitatus totius regni ex precepto regio in literis patentibus proposito quod in fide et virtute predictam chartam tenerent, et tenere nolentes, etiam regem ipsum, totis viribus infestarent'. |

26 | Surviving as an original sealed by the barons (TNA C 47/34/1/1), printed from a copy on the dorse of the Close Roll, on a membrane whose face deals with business of 11-19 July (TNA C 54/12 m.27d, also C 54/13 m.27d, cf. RLC, i, 268b), in Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 133; H. G. Richardson, ‘The Morrow of the Great Charter’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, xxviii (1944), 424–5 (with suggested dating to the Oxford Council of 16–23 July), and (with facsimile from the original) by Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 490–1, plates 10–11 (with commentary at pp.262–6, 486–8, and suggested dating to the field of Runnymede c.19 June. |

27 | RLP, 143b. |

28 | RLP, 143b. |

29 | RLC, i, 215.W |

30 | RC, 210-10b, where the last of the witnesses, 'William de Gameton', remains unidentified. |

31 | Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols. (London, 1872-73), ii, 221: 'Recepti sunt igitur in osculum pacis qui aderant, hominium et fidelitatem de nouo facientes, comederuntque simul et biberunt'. |

32 | The Chronicle of the Election of Hugh Abbot of Bury St Edmunds and Later Bishop of Ely, ed. R.M. Thomson (Oxford, 1974), 170-1. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)