A New Letter of the Twenty-Five Barons of Magna Carta

July 2015,

A week ago, as reported in the Times, we advertised the discovery of a new letter issued in the names of the Twenty-Five barons of Magna Carta, brought to light in a manuscript at Lambeth Palace Library. We had the audacity to claim this as the single most important Magna Carta discovery made in the past fifty years. The manuscript in question was catalogued in the early 1930s by M.R. James.1 In making his descriptions, James worked from his homes in Cambridge, Forthampton and later Eton, calling for the Lambeth manuscripts to be sent from London in regular batches.2 His description of Lambeth ms. 1213 is archetypal James, combining the rigorous and the slap-dash in more or less equal proportions. He thus noticed that the manuscript itself is a late thirteenth- early fourteenth-century compendium from St Augustine's Canterbury, acquired by Archbishop Parker but somehow detached from the main collection of Parker manuscripts intended for Corpus Christi College Cambridge. He listed its principal contents, including at pp.189-94 a copy of the 1215 Magna Carta followed by a variety of letters in the name of King John, mostall of them known from printed editions.3 However, he passed over the most significant item, here entirely unnoticed. If we turn to the manuscript itself, we find the following five items, of which James noted two or at best three:

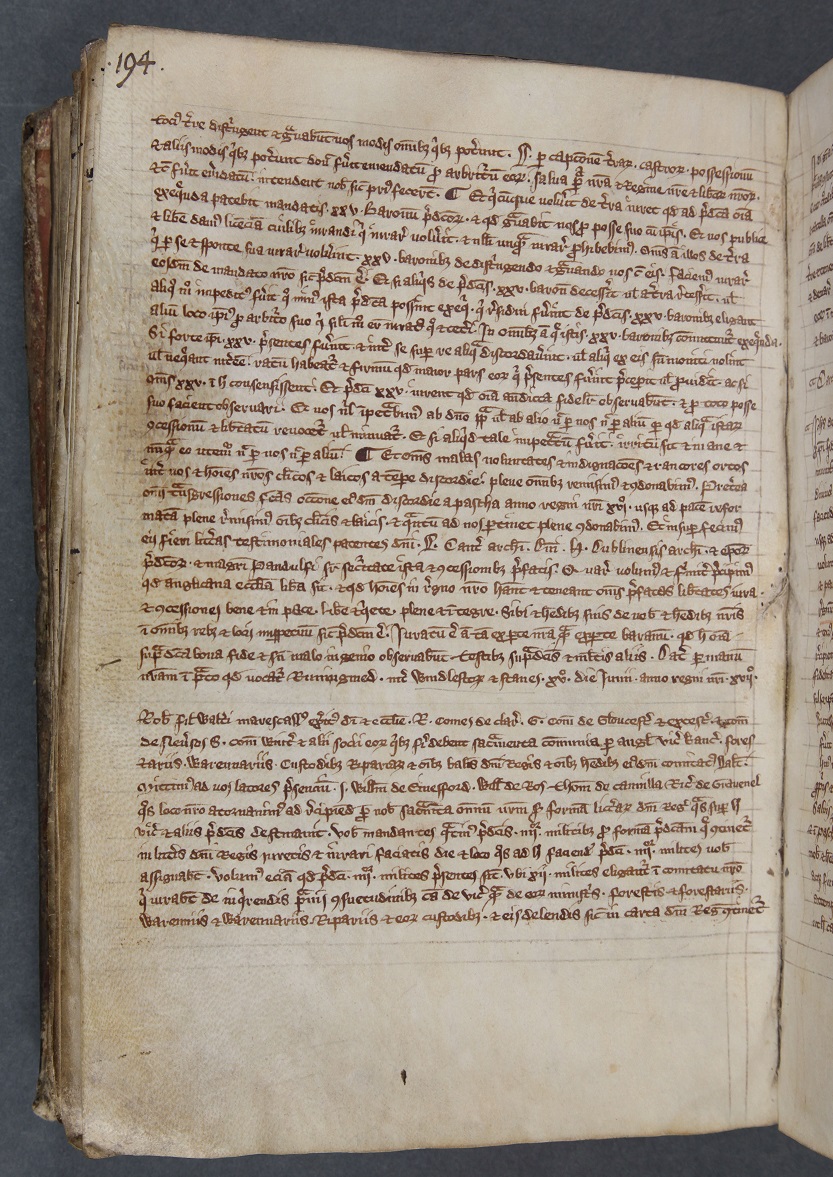

i. (pp.189-94) A copy of the 1215 Magna Carta. According to David Carpenter, who has made a detailed collation, this is the standard authorized text of 1215 but without the specific variations of the version known at Christ Church Canterbury as copied from the 'Canterbury' original of 1215 (BL Cotton Charter XIII.31b), and with variants to c.2 that do not otherwise appear in the 'Canterbury' original.

ii. (p.194) The letter published for the first time below (as appendix no.1), issued in the name of five of the twenty-five barons of Magna Carta addressed to the sheriff and others of Kent.

iii. (p.195) Undated letters patent of King John (published below as appendix no.2) addressed to the sheriff of Kent and the twelve knights in that county to enquire into and suppress bad customs in respect to sheriffs, their ministers, forests and foresters, warrens and warreners, river banks and their keepers, commanding them to seize into the King's hands all lands, tenements and chattels of those in Kent who resist the twenty-five in accordance with the terms of the charter of liberties. A version of this same letter as sent into Warwickshire is recorded in RLP, 145b, whence Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 134; J.C. Holt, Magna Carta (2nd edn., Cambridge, 1992), 496-7 no.11, with date at Winchester on 27 June 1215 and with notice that similar instructions were sent into all the counties of England.

iv. (p.195) King John's charter, undated, subjecting his realm to the papacy, known elsewhere from an inspeximus by the Pope, undated but closely associated with the King's oath sworn at the Templar house near Dover on 15 May 1213 (below no.v), whence Foedera, 111-12, from an original papal bull of 4 November 1213 (BL ms. Cotton Cleopatra E i fo.149), whence Foedera, 117; Letters of Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) concerning England and Wales: a calendar with an appendix of texts, ed. C. R. Cheney and M. G. Cheney (Oxford, 1967), 156 no.941).

v. (p.196) The King's oath of homage sworn at the Templar house near Dover on 15 May 1213, placing England and Ireland under the feudal lordship of the papacy, as reported elsewhere in Foedera, 112, 117, there from a papal inspeximus for which see above no.iv.

What we have here is a self-contained collection, closely associated with Kent and the monks of St Augustine's Canterbury, reciting texts from the later years of King John, including two items (nos. ii-iii) related directly to the enforcement of Magna Carta (no.i). Of all of these items, it is no.ii that is of greatest significance. This supplies a unique, albeit corrupt copy of a text crucial to our understanding of the process whereby Magna Carta was broadcast to the English counties immediately after its granting on 15 June 1215.

The letter itself is issued in the names of five men, all of them of the twenty-five. These same five men, in the same order, head the list of those granting the so-called 'London Treaty', itself one of only five texts known to survive issued in the names of the twenty-five. Once again, listing these in chronological order, our new letter fits into the following sequence of letters issued in the name of the twenty-five:

1. The Treaty over London (c.19/20 June 1215), surviving both as an original (TNA C 47/34/1/1, with slits for 13 tags and seals) and as a copy on the dorse of the Close Roll, on a membrane whose face deals with business of 11-19 July (TNA C 54/12 m.27d, also C 54/13 m.27d, cf. RLC, i, 268b). Printed from the enrolment: Foedera, 133; H. G. Richardson, ‘The Morrow of the Great Charter’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, xxviii (1944), 424–5 (with suggested dating to the Oxford Council of 16–23 July), and (with facsimile from the original) by Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 490–1, plates 10–11 (with commentary at pp.262–6, 486–8, and suggested dating to the field of Runnymede c.19 June). Issued as a cyrograph drawn up between the King on one side and on the other Robert fitz Walter 'Marshal of the army of God and holy Church in England', Richard de Clare earl (of Hertford), G(eoffrey de Mandeville) earl of Essex and Gloucester, R(oger) Bigod earl of Norfolk and Suffolk, S(aher de Quincy) earl of Winchester, R(obert de Vere) earl of Oxford, H(enry de Bohun) earl of Hereford 'and the following barons, namely' W(illiam) Marshal the younger, Eustace de Vescy, William de Mowbray, John fitz Robert, Roger de Montbegon, William de Lanvallay 'and other earls and barons and free men of the whole realm'. The King hereby agrees that the city of London should be held by the barons, and the Tower of London by the archbishop of Canterbury, until the coming feast of the Assumption (15 August 1215), allowing that meanwhile the oaths allowed for in the charter of liberties be administered as in 'the letters over the election of twelve knights to suppress bad customs of the forests and other things' (sicut continetur in litteris de duodecim militibus eligendis ad delendum malas consuetudines de forestis et aliis). Provided that the King meanwhile does all that he has promised to do, by counsel of the twenty-five, the city and the Tower are to be restored to him, the status quo ante bellum being re-established meanwhile for both sides, in terms of castles, lands and vills.

2. Our new letters (c.19/20 June 1215) (Lambeth Palace Library ms.1213 p.194, printed for the first time below) issued in the names of Robert fitz Walter 'Marshal of the army of God and the Church', R(ichard) de Clare earl (of Hertford), Geoffrey (de Mandeville) earl of Gloucester and Essex, the earl 'de Neuersos' (almost certainly a garbled version of the name of Roger Bigod earl of Norfolk), and S(aher de Quincy) earl of Winchester. These can clearly be identified as 'the letters over the election of twelve knights to suppress bad customs of the forests and other things' mentioned in the London Treaty (above no.1). This in turn assists us in dating the London Treaty to the period suggested by Holt (c.19/20 June) rather than to that assigned by Richardson (16-23 July).

3. Letters (c.July 1215) of Robert fitz Walter 'Marshal of the army of God and holy Church' and 'other magnates of the same army' addressed to William d'Aubigny (of Belvoir) warning him of the threat to London, the barons' chief 'stronghold' (receptaculum), informing him that the tournament held at Stamford on the Monday after the feast of SS Peter and Paul (itself in 1215 falling on Monday 29 June, so perhaps referring here to Monday 6 July) has been extended to the Monday after the octave of that feast (13 July) and that another tournament will be held near London between the heath of Staines and the vill of Hounslow, commanding William's presence there, when the prize will be a bear to be awarded by a unnamed 'lady'. Printed Foedera, 134 (with misleading reference as if from a copy enrolled on the dorse of the Close Roll 17 John (m.21d, whence, in theory, RLC, i, 269). In reality preserved only in the chronicle of Roger of Wendover, perhaps from information supplied by William d'Aubigny of Belvoir (Roger of Wendover, Flores Historiarum, ed. H.O. Coxe, (4 vols., London, 1842), iii, 321-2, whence Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard, (7 vols., Rolls series, 1872–83), ii, 614-15).

4. Letters (30 September 1215) of Geoffrey de Mandeville earl of Essex and Gloucester, Saher (de Quincy) earl of Winchester and Richard de Clare earl of Hertford, known from a late thirteenth-century copy (TNA SC 8/331 no.15693 no.12), witnessed by Robert de Vere earl of Oxford at London on 30 September 1215 (dated by the incarnation rather than the King's regnal year), commanding Brian de Lisle to obey the oath that he made 'at the suit of the common charter of the realm' (iuramentum quod fecistis ad sectam commune carte regni) to restore Knaresborough Castle to Nicholas de Stuteville as adjudged to him by the twenty-five barons. Should Brian fail to comply, he will forfeit the barons' fealty at the risk of his body, lands and chattels. Discovered and first printed by Richardson, ‘The Morrow of the Great Charter’, 443, whence Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 499 no.15.

5. Letters (30 September 1215) of Geoffrey de Mandeville earl of Essex and Gloucester, Saher (de Quincy) earl of Winchester and Richard de Clare earl of Hertford, known from the same late thirteenth-century copy as no.4 above (TNA SC 8/331 no.15693 no.13), witnessed by Robert de Vere earl of Oxford at London, 30 September 1215, addressed to Robert de Ros 'keeper' (custos) of Yorkshire, commanding him to ensure that all of the county, save those who the barons summoned to attend them (in London), assist Nicholas de Stuteville in the recovery of Knaresborough Castle. Discovered and first printed by Richardson, ‘The Morrow of the Great Charter’, 443, whence Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 499-500 no.16.

6. Various letters of the barons (1215/16), now lost, but recorded in an inventory of the archive of the Scottish royal treasury, 29 September 1282: Edinburgh, National Archives of Scotland RH5/8/1, whence printed in Foedera, I part 2, 615-17; The Acts of the Parliament of Scotland, ed. T. Thomson and C. Innes, (12 vols., Edinburgh, 1814-75), i, 107-10; (brief calendar) J. Bain, Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, (4 vols., 1881-), ii, 68-9 no.225: 'Item confederatio inter regem Scot(ie) et barones Anglie olim facta. Item adiudicatio terrarum Northumbrie et Cumbirlandie et Westmerlandie per barones Angl(ie) regi Scot(ie). <Item> littera conuentionalis inter regem Scot(ie) et barones Angl(ie) super quibusdam matrimoniis. Item mandatum baronum Angl(ie) facta ciuitati Carliol’ super redditione et adiudic<atione terra>rum Northumbr’ Cumbirland’ et Westmerland’ ... Item mandatum baronum Angl(ie) directum baronibus Northumbr’, Cumbirland’ et Westmerlandie per regem Scot(ie) .... Item littera maioris et burgensium Lundon' .... Item excusatio nunciorum reg(is) Scot(ie) facta per quosdam magnates Angl(ie) et de alia securitate facta per eosdem super quadam summa pecunie deponenda ad Templum Lundon .... Item littera Roberti de Ros’ et Eustacii de Vescy'.

As no.6 here should make apparent, the twenty-five barons can be assumed to have issued a large number of letters, now lost. Even so, the significance of our Lambeth letter (above no.2) derives not just from the rarity of its survival but from the new and specific details that it supplies. Here we find five of the twenty-five (Robert fitz Walter, Richard de Clare, Geoffrey de Mandeville, ?Roger Bigod, and Saher de Quincy) informing the sheriff, foresters, warreners, keepers of river banks, the King's bailiffs and all the men of Kent (the word hominibus here having been miscopied as heredibus) that they have sent the bearers of the present letters, named as William of Eynsford, William de Ros, Thomas de Canville and Richard of Graveney, appointed in the name of the barons to receive the oaths of all those who are swear oaths to the barons in accordance with the letters issued by the King, receiving these oaths at a time and place to be determined by the four knights who are themselves to be present when twelve knights are elected in the county to enquire into evil customs concerning sheriffs, forests and foresters, warrens and warreners, river banks and their keepers, suppressing such evil customs in accordance with 'the King's charter' (i.e. Magna Carta). The intention here was clearly to enforce the terms of two distinct clauses of Magna Carta. Clause 48 of the charter had demanded investigation and suppression of all evil customs of forests, warrens, foresters, warreners, sheriffs and their ministers, river banks and their keepers, to be conducted within 40 days by twelve knights sworn in each county chosen by the men of the county.4 The charter's final, 'securities' clause made provision for whoever so wished to swear oaths to assist the twenty-barons of the charter in harassing the King into compliance with the charter's terms. All those who did not wish to swear such oaths would be obliged to do so, by the King's command.5

Precisely these same clauses of Magna Carta had been the subject of two sets of royal letters, long known from their copying into the chancery rolls. The first issued on 19/20 June to each of the counties of England had announced the making of a 'firm peace' and had commanded the sheriffs to have Magna Carta read in public, administering the oaths to the twenty-five decreed by the charter 'in the presence of the twenty-five or those whom they may attorn to this purpose by their letters patent' (attornauerint, the same verb found in our new letters of the twenty-five, atornauimus) ensuring the election of the twelve knights provided for under the terms of the charter's clause 48 'in the next county court held in your parts after the receipt of their letters'.6 The second letter, dated at Winchester on 27 June, commanded the sheriffs of England and the twelve knights elected to enquire into and suppress evil customs to seize into the King's hands all lands, tenements and chattels of those who had refused to swear the oaths required to the twenty-five.7

As this suggests, the election of the twelve knights and the swearing of oaths must have taken place between 19 and 27 June, allowing our letters of the twenty-five to the county of Kent to be dated to c.19/20 June. Since this same process, including the letters of the twenty-five are referred to as still ongoing in the terms of the London treaty negotiated between the King and the twenty-five, this supplies confirmation that the London treaty should be assigned to c.19/20 June, as argued by Holt, rather than to July as argued by Richardson or as suggested by the treaty's copying on to the dorse of a membrane of the Patent Roll dealing with business of 11-19 July.8

So far so good. But now we come to two truly remarkable features of our newly discovered letters at Lambeth. The first concerns their role in the peace-making process of June 1215. As noted in the media commentary on their rediscovery, they supply evidence that it was not just the King who moved to enforce Magna Carta in mid June, but that the barons themselves took a direct role both in the appointment of four representatives to uphold their interests in Kent and other English counties, and in the wider administration of the oaths and inquests provided for under the terms of the charter's securities clause and clause 48. Although such a role has previously been suspected, our letters supply incontrovertible proof of its revolutionary nature. For a brief period after Runnymede, in late June 1215, the barons took responsibility for local government, sending out instructions in their own name to the King's sheriffs and other officers. Such a situation has previously been supposed to have occurred first in 1258, when the barons of Henry III seized control both of central and local government. Our letters show dual-control by King and barons operating a full forty-three years before the 'revolution' of 1258, in 1215. No wonder that the King's foreign mercenaries are said to have jested that, as a result of his agreement to the committee of twenty-five barons, the King had himself become merely one amongst twenty-five kings in England.9

Secondly, we are here supplied with the names of the four knights attorned by the barons to administer the implementation of the peace in Kent. All four of them are well-documented. William of Eynsford (d.1231) held extensive estates both from the archbishopric of Canterbury (seven and a half fees including Eynsford, Ightham and Ruckinge in Kent, and the manor of Toppesfield in Essex) and from the bishops of Lincoln (at least four fees at Great Staughton in Huntingdonshire and elsewhere).10 Already in rebellion by June 1215, he seems to have been reconciled to the King at Runnymede but rejoined the rebels at the siege of Rochester where he was taken prisoner, being eventually released by the ministers of Henry III in return for a ransom of at least 450 marks.11 William de Ros was a minor Kentish baron who also held one and a half fees of the archbishopric of Canterbury, at Cossington and Cooling, confirmed as a portion of the archbishopric estate by King John in a charter of July 1202.12 William was at this time, and perhaps as late as 1205, still under age.13 His other estates included Farningham (close to Eynsford), and Lullingstone, held of the earldom of Gloucester.14 His grant to Southwark Priory of a hermitage at Plumstead in Greenwich was witnessed by various leading Londoners, including a son of London's first mayor, Henry fitz Ailwin.15 He has not previously been recorded in the rebel camp before Runnymede, and as late as 1 November 1215 was the object of favours from the King.16 By 10 November, however, he was in rebellion, perhaps with those at Rochester. He was later taken prisoner and by September 1216 had offered a ransom of more than 500 marks.17 Thomas de Canville, perhaps the son of Hugh de Canville, himself son of the courtier Richard de Canville (d.1176), held at least three fees of the honour of Boulogne including Westerham in Kent and Fobbing and Shenfield in Essex.18 He was in rebellion by December 1215, when his family estate at Godington in Oxfordshire was seized.19 In September 1217 he was restored to his lands in Kent, Essex and Oxfordshire and to unspecified estates in Buckinghamshire and Huntingdonshire.20 The fourth and final knight mentioned in June 1215, Richard of Graveney, held Graveney in Kent as two fees of the archbishopric of Canterbury, and Tooting Graveney in Surrey, of Chertsey Abbey.21 Before September 1215, he appeared alongside William of Eynsford in the witness list to a charter of Archbishop Langton converting the church of Ulcombe into a college for three priests.22 He was in rebellion by 2 November 1215, whereafter his land both at Tooting and Graveney was granted to royalists.23

What should by now be apparent is that at least three of these four knights held land in Kent from archbishop Langton. We have elsewhere questioned the standard account of Langton's political position in the summer of 1215, according to which the archbishop strove to serve as a neutral arbiter, brokering peace between King and barons.24 Amidst the mounting tide of evidence that Langton's sympathies lay more with the barons than with the King, the present proof that three of his knights were appointed to act as representatives of the baronial twenty-five in Kent surely reveals a further aspect to the archbishop's involvement in the rebel cause, even as early as June 1215. David Carpenter points out to me that none of these four knights was entirely Langton's man. William of Eynsford and William de Ros were both barons in their own right, capable of autonomous political action. Nonetheless, the role played by the archbishop's knights in imposing oaths to the twenty-five and in securing the appointment of the twelve inquisitors into royalist misdeeds in Kent, surely implicated Langton in the rebel cause to a degree never before suspected.

For all of these reasons, our new letters are indeed a most significant discovery. Since Richardson's unearthing of the baronial letters concerning Knaresborough Castle (above nos.3-4), in 1944, no document more important has emerged from the archives, touching directly upon events at Runnymede and the peace settlement of June 1215.25

APPENDIX

1. Letters of five of the twenty-five barons, appointing four knights to oversee the swearing of oaths and the appointment of an inquest by twelve knights in the county of Kent. [?Runnymede, c.19/20 June 1215]

B = London, Lambeth Palace ms. 1213 p.194, s.xiii/xiv.

Rob(ertus) fil(ius) Walteri Marescallus exer(c)itus Dei et ecclesie, R(icardus) comes de Clar', G(alfridus) com(es) de Gloucest' et Excest' et com(es) de aNeuersosa, S(aher) com(es) Wint' et alii socii eorum quibus fieri debent sacramenta communia per Angl(iam), vic(ecomiti) Kanc', forestariis, warennariis, custodibus ripararum et omnibus bal(liu)is domini regis et omnibus bheredibusb eiusdem comitatus salutem. Mittimus ad vos latores presencium, s(cilicet) Will(elmu)m de Einesford, Will(elmum) de Ros, Thom(am) de Canuilla, Ric(ardum) de Grauenel, quos loco nostro atornauimus ad recipiend(um) pro nob(is) sacramenta omnium v(est)r(oru)m s(icut) formam litterarum domini reg(is) quas super hoc vic(ecomiti) et aliis predictis destinauit, vob(is) mandantes quatinus predictis iiii.or militibus s(icut) formam predictam que continetur in litteris domini regis iuretis et iurari faciatis die et loco quos ad hoc faciend(um) predicti iiii.or milites vob(is) assignab(un)t. Volumus eciam quod predicti iiii.or milites presentes sint ubi xii. milites eligantur in comitatu cnostroc qui iurabunt de inquirendis prauis consuetudinibus tam de vic(ecomitibus) quam de eorum ministris, forestis et forestariis, warenniis et warennariis, ripariis et eorum custodibus et eis delendis sic(ut) in carta domini reg(is) continetur.

Robert fitz Walter Marshal of the army of God and the Church, R(ichard) de Clare earl (of Hertford), G(eoffrey de Mandeville) earl of Gloucester and Essex and the earl of ?Norfolk, S(aher de Quincy) earl of Winchester, and their other associates to whom communal oaths are owed throughout England, send greetings to the sheriff of Kent and to the foresters, warreners, keepers of river banks and all the King's bailiffs and all ?men of the same county. We have sent to you the bearers of the present letters, namely William of Eynsford, William de Ros, Thomas de Canville and Richard of Graveney, whom we attorn in our place to receive on our behalf the oaths of all you as in the letters of the lord King which he sent to the sheriff and the others aforesaid, ordering you that you swear oaths to the aforesaid four knights as in the form set out in the lord King's letters, and that you have oaths made at a certain time and place to be determined by the aforesaid four knights. We wish moreover that the aforesaid four knights be present when the twelve knights are elected in your county who will swear oaths to enquire into evil customs committed by sheriffs and their ministers, in regard to forests and foresters, warrens and warreners, river banks and their keepers, and to ensure the suppression of such evil customs as is set out in the lord King's charter.

2. Letters of the King commanding the twelve knights chosen in Kent to enquire into evil customs to seize the lands of those who have refused to swear oaths to the twenty-five barons. [Winchester, 27 June 1215]

B = London, Lambeth Palace Library ms. 1213 p.195, s.xiii/xiv.

I(ohannes) Dei gratia rex Angl(ie) et cetera vic(ecomiti) Kanc' et xii. militibus electis in eodem comitatu ad inquirend(um) et delend(um) prauas consuetudines de vic(ecomitibus) et eorum ministris, forestis et forestariis, warenniis et warenariis, ripar(iis) et eorum custodibus salutem. Mandamus vobis quod statim sine dilatione seisiatis in manum nostram terras, tenementa et catella omnium illorum de com(itatu) Kanc' qui iurat(i) contradixerint xxv. baronibus secundum formam contentam in carta nostra de libertatibus vel eis quos ad hoc atornauerint, et si iurar(e) voluerint, statim post xv. dies completos postquam terre et tenementa illorum et catalla in manum nostram saisita fuerint, omnia catella sua vendere faciatis et denar(ios) inde perceptos saluo custodiatis deputandos dsubsidiod Terre Sancte. Terras a(utem) et tenementa eorum in manu nostra teneatis quousque iurauerint. Hoc quidem prouisum fuit per iud(icium) domini Cant' archiepiscopi et baronum terre nostre regni nostri.

John by God's grace King of England etc sends greetings to the sheriff of Kent and to the twelve knights elected in the same county to enquire into, and to suppress, evil customs concerning sheriffs and their ministers, forests and foresters, warrens and warreners, river banks and their keepers. We order you that immediately and without delay you seize into our hands the lands, holdings and chattels of all those of the county of Kent who by oath have defied the twenty-five barons in accordance with the terms set out in our charter of liberties, and those whom they have attorned to the same, and if they so swear, immediately after fifteen days have elapsed after their lands and holdings and chattels shall have been seized into our hands, have all their chattels sold and the money thus received kept safely, deputed to the needs of the Holy Land. Their lands and tenements, however, are to be kept by you in our hands so long as they so swear. This was established by judgement of the lord archbishop of Canterbury and the barons of our land and realm.

asic B, ?recte Rogerus Bigot comes Northfolc' et Suthfolc' bsic B, ?recte hominibus csic B, recte vestro dfulsidio B, subsidio supplied

1 | Montague Rhodes James, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Lambeth Palace, originally published as five fascicules (Cambridge, 1930-1932). |

2 | For James' work on the Lambeth manuscripts, begun in 1900, continued after 1915, see R.W. Pfaff, Montague Rhodes James (London, 1980), 204-5, 281-7, at p.284 noting that the resulting catalogue 'has the usual plethora of mistakes, of greater or lesser magnitude'. |

3 | James, Descriptive Catalogue, 834-40, esp. p.837 no.18 ('Carta regis Johannis data apud Runingmed et carta eiusdem de subiectione eiusdem Curie Romane'), whence the much briefer notice in G.R.C. Davis, Medieval Cartularies of Great Britain (London, 1958), 24 no.201 (2nd edn. by Claire Breay, Julian Harrison and David M. Smith (London, 2010), no.201). James' description is a great deal fuller than that by Henry J. Todd, A Catalogue of the Archiepiscopal Manuscripts in the Library at Lambeth Palace (London, 1812), 264b. |

4 | Magna Carta c.48: 'Omnes male consuetudines de forestis et warennis, et de forestariis et warennariis, vicecomitibus, et eorum ministris, ripariis et earum custodibus, statim inquirantur in quolibet comitatu per duodecim milites iuratos de eodem comitatu, qui debent eligi per probos homines eiusdem comitatus, et infra quadraginta dies post inquisitionem factam, penitus, ita quod numquam revocentur, deleantur per eosdem, ita quod nos hoc sciamus prius, vel iusticiarius noster, si in Anglia non fuerimus'. |

5 | Magna Carta, securities clause: 'Et quicumque voluerit de terra iuret quod ad predicta omnia exsequenda parebit mandatis predictorum viginti quinque baronum, et quod gravabit nos pro posse suo cum ipsis, et nos publice et libere damus licentiam iurandi cuilibet qui iurare voluerit, et nulli umquam iurare prohibebimus. Omnes autem illos de terra qui per se et sponte sua noluerint iurare viginti quinque baronibus, de distringendo et gravando nos cum eis, faciemus iurare eosdem de mandato nostro, sicut predictum est'. |

6 | Foedera, 134, from a copy on the dorse of the Patent Roll specifiying no particular sheriff (RLP, 180b), dated at Runnymede, 19 June 1215, with an original directed to the sheriff of Gloucestershire, dated at Runnymede, 20 June 1215, preserved at Hereford Cathedral Archives charter no.2256, whence Ifor Rowlands, 'The Text and Distribution of the Writ for the Publication of Magna Carta, 1215', English Historical Review, cxxiv (2009), 1422-31. |

7 | Surviving on the dorse of the Patent Roll in a version addressed to Warwickshire (RLP, 145b, whence Foedera, 134; Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 496-7 no.11) and in our Lambeth manuscript (above no.iii and below appendix no.2) in a version addressed to Kent. |

8 | Cf. above no.1. |

9 | Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. Luard, ii, 611. |

10 | F.R.H. Du Boulay, The Lordship of Canterbury: An Essay on Medieval Society (London, 1966), 342-3; H.M. Colvin, 'Archbishop of Canterbury's Tenants by Knight-Service in the Reign of Henry II', Documents Illustrative of Medieval Kentish Society, ed. F.R.H. Du Boulay (Ashford, 1964), 16 no.7; VCH Huntingdonshire, ii, 355-6; Red Book of the Exchequer, ed. Hall, i, 289, 376, 471-2, 517, 726. |

11 | The Letters and Charters of Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, Papal Legate in England 1216-1218, ed. N. Vincent, Canterbury and York Society 83 (1996), no.2n.; Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. Luard, ii, 626; RLC, i, 216b, 295; RLP, 195b; Patent Rolls 1216-25, 7, 13, 20. |

12 | Du Boulay, Lordship of Canterbury, 357; Colvin, 'Archbishop of Canterbury's Tenants', 23 no.21; Red Book of the Exchequer, ed. Hall, i, 135, 196-7, ii, 471-2, 726; Lambeth Palace Library ms. Chartae Antiquae XI.12. |

13 | Curia Regis Rolls, i, 187; RLC, i, 50. |

14 | The Register of St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury, Commonly Called the Black Book, ed. G.J. Turner and H.E. Salter (2 vols., London, 1915-24), i, 10; W. Farrer, Honors and Knights' Fees (3 vols., London 1923-5), iii, 194-6. |

15 | Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals, ed. D.M. Stenton and L.C. Loyd (Oxford, 1950), 116-17 no.160. |

16 | RLC, i, 227, 234. |

17 | RLC, i, 235b, 239, 252, 253, 351; RLP, 197, 199. |

18 | Hatton's Book of Seals, 8 no.10n.; Red Book of the Exchequer, ed. Hall, i, 134, 175, 475, 501, 582; Book of Fees, i, 239, 242, 485, ii, 1432, 1436. |

19 | RLC, i, 243; VCH Oxfordshire, vi, 147-8. |

20 | RLC, i, 325, 327b. |

21 | Du Boulay, Lordship of Canterbury, 346-7; Colvin, 'Archbishop of Canterbury's Tenants', 20-1 no.16; Red Book of the Exchequer, ii, 471, 606, 726; Book of Fees, i, 687. |

22 | Acta Stephani Langton Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi AD 1207-1228, ed. K. Major, Canterbury and York Society l (1950), 37 no.27. |

23 | RLC, i, 234, 237b. |

24 | See King John's Diary for 25-31 January, 24-30 May, and 31 May-6 June 1215. |

25 | I would suggest that the Lambeth letters are at least as significant as the materials elucidating Magna Carta clauses 56-8 published nearly thirty years ago by J. Beverley Smith, 'Magna Carta and the Charters of the Welsh Princes', English Historical Review, xcix (1984), 344-62. |

Referenced in

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels (Features of the Month)

Magna Carta and Peace (The Itinerary of King John)

Magna Carta and Peace (The Itinerary of King John)

Magna Carta and Peace (The Itinerary of King John)

John and the siege of Rochester: week four (The Itinerary of King John)

Rochester is garrisoned by the rebels (The Itinerary of King John)

John restores the land of former rebels (The Itinerary of King John)

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265