King John’s Lost Language of Cranes: Micromanagement, Meat-Eating and Mockery at Court

March 2015,

In the midst of the King's many political concerns, it is remarkable how often we find royal letters concerned with seeming trivia. The orders translated below were sent on Monday 16 March 1215 to John fitz Hugh, almost certainly in his capacity as constable of Windsor Castle.1 Besides being instructed to receive four falcons, one of them described as the best that the King possessed, John fitz Hugh was given detailed commands on the diet to be fed to these birds ('fat goats', 'good' chickens, and the meat of hares at least once a week). To ensure the falcons' safety in their mews, he was to seek out the best mastiffs as guard dogs. There can be no certain proof here, but the insistence on a very particular diet, and the reference to the gyrfalcon 'than which we have no better', strongly suggest that these instructions came direct from the King. They support the impression obtained from other royal letters that King John was inclined to micromanagement, in particular of those matters that lay closest to his heart: his jewels, his prisoners, his hawks and his hounds.

Some of the details in the translated letter require explanation. The 'gyrfalcon of Gibbun' mentioned here was presumably one of the hawks kept by a falconer named Gibbun. This man is mentioned on other occasions.2 He seems to have been a difficult servant to manage. In November 1214, sending hawks to hunt at Durham, the King gave instructions that their keeper, Ralph of Earlham, was to be received and paid his wages, 'unless there should be dispute (lis) between him and Gibbun, in which case send Gibbun back to us'.3 Falconry was a winter sport whose season ran from roughly September to March each year. For the remaining six months, falcons were kept in huts of wood and wattle, known as 'mews'. By John's reign, an extensive literature was already devoted to their training, diet and flight.4 Adelard of Bath, tutor to John’s father, Henry II, wrote one of the more famous such treatises, itself claiming to draw upon knowledge transmitted from ‘King Harold’s books’: lost learning from the reign of the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings.5 A common devotion to hawking no doubt contributed to the particular love that Henry II is said to have shown for his youngest son, the future King John.

Gyrfalcons, from Norway, were prized in particular for use against cranes, herons and duck. The King's insistence that his own gyrfalcons be fed on hare meat at least once a week accords with accepted custom, whereby diet was intended to discourage fat, and training for falcons intended to fly against cranes and herons was undertaken with flight first against lures and then against live hares. Like the hare, the heron makes sudden twists and turns that the falcon had to learn to predict. Cranes, by contrast, escape through long straight flights. Both herons and cranes are capable of defending themselves, the heron with its beak, the crane with its claws.6 Meanwhile, it was in order to protect their sport that both Henry II and King John forbade others to hunt along rivers where game abounded. Known as placing such rivers in 'defence', this exercise of royal privilege not only explains the King's arrest of fowlers found taking birds within five leagues of 'our rivers' of Dorset in 1213, but finds a place in Magna Carta clause 47.7 Here, besides promising the deforestation of all land newly afforested, the King was obliged to promise similar release for 'all riverbanks that we have put in defence in our time'.8

Of King John's love of crane hunting there is no doubt.9 In 1212, for example, the King fed fifty paupers in penance for each of the seven cranes that he had hunted on Holy Innocents' Day (28 December).10 There is perhaps some insight here into the King's psychology. Just as today's would-be Ernest Hemingways, Vladmir Putin amongst them, dream of hunting the very largest animals, bears or elephants, so the crane was the largest and most conspicuous target for medieval falconers. As the King's instructions on diet make plain, falconry was a lethal sport that involved setting the swift and carnivorous to attack the slow and relatively defenceless. This could easily have been viewed, in the Middle Ages, as a metaphor for kingship. Certainly, in a well known metaphor, apparently transformed into a wall painting for the King’s castle at Winchester, Henry II is said to have likened himself to an eagle torn apart by its young.11 The obligation of kings to shed blood in hunting, as in war or justice, was one that John like his Plantagenet ancestors was determined to fulfil.12 It was in deliberate and publicly advertised reaction against the Plantagenet addiction to bloodsports that the French King, Philip Augustus, having been offered a great shipload of live deer and other beasts as a diplomatic gift by King John's father, insisted that these animals be kept, not for hunting, but as a live menagerie in his park at Vincennes. In doing so, he challenged the authority of his Plantagenet rivals, exposing Henry II himself as a ruler steeped in predation and bloodshed, not least for his role in the murder of his own archbishop, the martyred St Thomas of Canterbury.13 As Gesine Oppitz-Trotman has shown, hawking itself occurs as a distinctive topos in the miracles recorded of Becket at Canterbury, including in several instances the archbishop's cure of injured hawks, at least one of them belonging to King Henry II.14

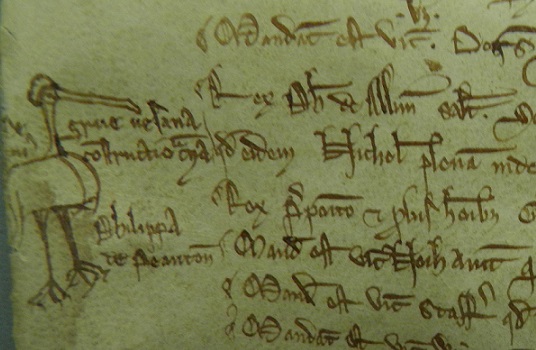

Meanwhile, there are perhaps further insights to be obtained from King John's love of crane hunting. Clerks in the royal chancery had long been accustomed to doodling or inserting informal comments in the margins of official records.15 It was by such means that, in the 1160s, we find the compiler of an Exchequer Roll ending one particular entry with the statement (no doubt inserted for humourous effect) that 'Richard de Neville is a bad, black man'.16 Most famously, in the 1230s, another royal clerk decorated the entire end of an Exchequer Receipt Roll with an elaborate depiction of the Jewish money lender, Isaac of Norwich.17 A far cruder doodle is to be found on the Close Roll for the year 18 John, inserted in the left hand margin of the roll next to a royal letter of August 1216.18 Reminding us of the King's interest in falconry and in particular in hunting for cranes, this shows a picture of a large bird, and next to it the rhyming couplet: De grue versana, cuius constructio crana. Beneath is written the name Philippa de Peauton. The couplet, combining both Latin (grus) and English (crane), can be translated as 'The mad bird (crane), whose shape informs the crane (for building)'. What was intended here was probably a caricature of a woman, named Philippa of Paulton, depicted here in the guise of a crane, a bird famous both for its size and for its distinctively plaintive cry.19 Other such caricatures, both of men and of women, Jews and Christians, appear elsewhere in the chancery rolls, although none with quite this zoomorphic slant.20 This particular picture appears next to a writ addressed to Philip d'Aubigny, constable of Bristol, notifying him of the King's grant to Nicholas de Hadham of the land of the rebel Richard Talbot in Timsbury (Tymbrebir') and Whaddon. Timsbury in Somerset lies only three miles north-east of Paulton.21

Nothing is otherwise recorded of Philippa. However, a man named Roger of Paulton, who could perhaps have been Philippa's husband or father, can be found occasionally on the fringes of the royal court. A native of Paulton between Bath and Wells, he appears from 1204 onwards as a Somerset knight.22 In 1213-14, as deputy to the King's chancellor Richard Marsh, he accounted briefly as under-sheriff for Dorset and Somerset and as keeper of the Dorset abbey of Abbotsbury.23 By June 1216, Roger was in rebellion against the King.24 Shortly after King John's death, he was issued with letters of safe conduct to discuss his affairs.25 Restored to his lands, in 1218-19, he fined 50 marks to marry a neighbouring widow, Eva/Eve, daughter of Hawise de Gournay and former wife of Thomas son of William of Harptree.26 He was dead by September 1224, when the sheriff of Somerset was ordered to seize all his chattels pending settlement of his debts to the crown.27 He left a son, John of Paulton, himself perhaps identifiable in the early 1220s with a namesake who appears as regular witness to charters issued by Richard Marsh as bishop of Durham.28 If so, then we would have proof not only that Roger and John of Paulton both served in Richard Marsh's household but, more significantly, some indication that Marsh himself had Somerset connections. This, in turn, might allow us to suggest a link, not previously suspected, between Master Richard, the King's chancellor, and the Somerset family of Marsh or de Marisco of Huntspill, from which sprang Geoffrey de Marisco, John’s justiciar for Ireland, and William de Marisco, notorious pirate lord of Lundy.29

Meanwhile, Roger of Paulton's connections to Richard Marsh as chancellor and sheriff of Somerset, might explain why the chancery staff took so particular an interest in the appearance of Philippa of Paulton, Roger's wife or daughter. Philippa had perhaps attended court in August 1216 in order to plead on behalf of Roger, a former royal servant now turned rebel. The resulting caricature of her is no masterpiece. Even so, it supplies yet further insight into the humour of King John's court. It mocks as a 'mad crane' a woman who, for all we know, had good cause to lament the King's hawk-like ruthlessness. Just as John's micromanagement of his falcons and falconers supplies a glimpse into the King's psychology, so the decision of his clerks to use the crane as a metaphor for ungainliness or derangement suggests a court that delighted in the victimization not just of animals but of its human supplicants.

One final and even more tenuous speculation. The European crane is a bird that has recently been reintroduced to East Anglia, following a period of several centuries in which the draining of the eastern Fenlands effectively destroyed its habitat. Noting this connection between the Fen country and cranes, and given that it was only from September onwards that the King's hawks were considered fit to hunt, is it possible that the King's movements in the last weeks of his life were determined not just by military strategy but by sport? Certainly, the King's itinerary between 8 and 13 October 1216, from Spalding to King's Lynn and thence to Wisbech and Swineshead, would have taken him through prime crane-hunting country. Was it John's love of crane hunting that led to the fateful mistakes of his final few days, to the loss of his baggage train in the Wash, and to his own last illness and death at Newark?30 If so, then we have even further reason to rejoice that the chancery rolls record not just high politics but the doodling of the King's scribes and such seeming trivia as the King's insistence on the feeding of his falcons with fat goats and hare meat.

Letters to John fitz Hugh (constable of Windsor Castle). Geddington, 16 March 1215

B = TNA C 54/10 (Charter Roll 16 John) m.6 C = TNA C 54/9 (Duplicate) m.6.

Pd (from B) RLC, i, 192.

Rex Ioh(ann)i fil(io) Hug(onis) etc. Mittimus ad vos per W(illelmum) de Merc' et R(adulphum) de Erleham tres girfalcon(es) et girfalc(onem) Gibbun(i), quo meliorem non hab(emus), et unum falconem gentilem, mandantes quod eos recipiatis et in mutis poni faciatis et ad opus eorum pingues capras queri faciatis et aliquando bonas gallinas et singulis septim(anis) eis habere faciatis semel carnem leporum, et ad mutas custodiend(as) queratis bonos mastiuos. Custum autem quod posuitis in custod(em) falconum illorum et expensis Spark(elini) hominis W(illelmi) de Merc' qui eos custodiet cum i. homine et i. equo comp(utetu)r vob(is) ad sc(ac)c(ariu)m. T(este) me ipso ad Getindton', xxi. die Marc(ii) anno r(egni) n(ostri) xovio.

The King to John fitz Hugh. We are sending you, via W(illiam) de Merk and R(alph) or Earlham, three gyrfalcons, and Gibbun's gyrfalcon, than which we have no better, and a 'gentle' falcon, ordering that you receive them and place them in the mews, and seek out fat goats for them, and from time to time good chickens, and each week ensure that they are fed on the meat of hares, and find good mastiffs to guard the mews. The cost that you incur in keeping these falcons, and the expenses of Spark(elin) the man of W(illiam) de Merk, their keeper, with a man and a horse, will be accounted to you at the Exchequer. Witnessed by the King himself at Geddington, 21 March in the 16th year of our reign (1215).

1 | For John fitz Hugh as constable of Windsor from 1200 to at least 1214, see S. Bond, 'The Medieval Constables of Windsor Castle', English Historical Review, lxxxii (1967), 244-5. In 1214, he accounted for the expenses of the Windsor mews: Pipe Roll 16 John, 122. |

2 | RLC, i, 179, 190, 248b. For the other falconers mentioned below, Wiliam de Merk/Mark and Ralph of Earlham, see Pipe Roll 16 John, 41, 43-4; RLC, i, 179. Ralph was a member of the Hauville clan, a prominent family of royal falconers: Robin S. Oggins, The Kings and their Hawks: Falconry in Medieval England (New Haven, 2004), 65, 71, 168 nn.6, 9. For William de Merk, ibid., 69, 171 n.46 |

3 | RLC, i, 179. |

4 | The standard authority here is now Oggins, Kings and Hawks. |

5 | Adelard of Bath, De Cura accipitrum, ed. A.E.H. Swaen (Gröningen, 1937), and cf. Louise Cochrane, Adelard of Bath: The First English Scientist (London, 1994), 53-61. |

6 | Oggins, Kings and Hawks, 13-14, 16-18, 28-32. |

7 | Oggins, Kings and Hawks, 66-7, citing RLP, 100b (a letter of 22 June 1213, ordering Brian de Lisle to release fowlers in Dorset: Mandamus tibi quod oiselatores qui capti fuerunt in com(itatu) Dors' eo quod aues ceperunt in riuariis nostris et sunt in prisona nostra et custodia tua deliberes et abire permittas, accepto ab eis sacramento quod prope riuarias nostras per quinque leucas aues decetero non capient), and cf. Roger of Wendover's report that, at Christmas 1208, the King forbade the taking of birds throughout England (Roger of Wendover, Flores Historiarum, ed. H.O. Coxe (4 vols., London, 1842), iii, 225: rex Anglorum Iohannes ad Natale Domini fuit apud Bristollum et ibi capturam auium per totam Angliam interdixit). |

8 | Magna Carta (1215) c.47: ita fiat de ripariis que per nos tempore nostro posite sunt in defenso, and cf. c.48 referring to warreners and the keepers of riverbanks. |

9 | Oggins, Kings and Hawks, 68-9. See also Henry Summerson's Academic Commentary on clause 23 of Magna Carta. |

10 | 'Misae Roll 14 John', in Documents Illustrative of English History in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, ed. H. Cole (London, 1844), 250, and for further such instances, cf. Oggins, Kings and Hawks, 69. For the King's girfalcons sent to Berkshire to hunt for cranes, even at the height of the siege of Rochester in November 1215, see RLC, i, 240. |

11 | Gerald of Wales, ‘De Principis Instructione’ (III.26), in Giraldi Camrensis Opera, ed. J. S. Brewer, J. F. Dimock and G. F. Warner (8 vols., Cambridge, 2012), viii, 295-6, here singling out the youngest of the brood (i.e. the future King John) as potentially the most vicious. |

12 | For bloodshedding as a duty of kings, see the references assembled by N. Vincent, 'The Court', in Henry II: New Interpretations, ed. C. Harper-Bill and N. Vincent (Woodbridge, 2007), 322-3. |

13 | Rigord, in Oeuvres de Rigord et de Guillaume le Breton, ed. H.F. Delaborde, (2 vols., Paris, 1882-5), i, 34-5, and see the commentary by P. Buc, L’Ambiguité du livre: prince, pouvoir, et peuple dans les commentaires de la Bible au Moyen Age (Paris, 1994), 113, 117-18. |

14 | Gesine Oppitz-Trotman, 'Birds, Beasts and Becket: Falconry and Hawking in the Lives and Miracles of Thomas Becket', in God's Bounty? The Churches and the Natural World (Studies in Church History 46), ed. P. Clarke and T. Claydon (Woodbridge, 2010), 78-88. |

15 | In general, see Andrew H. Hershey, Drawings and Sketches in the Plea Rolls of the English Royal Courts, c.1200–1300, List and Index Society Special Series 31 (2002), and Ben Wild and Richard Cassidy's Fines of the Month, on the Henry III Fine Rolls website: B. L. Wild, 'Images and Indexing: Scribal Creativity in the Fine Rolls, 1216-1234' (Fine of the Month, April 2007) and R. Cassidy, 'Marginal Characters and Comments in the Rolls' (Fine of the Month, June 2008). |

16 | Pipe Roll 13 Henry II, 208. |

17 | TNA E 401/1565, several times printed, for example by John Gillingham, The Life and Times of Richard I (London, 1973), 54-5. |

18 | TNA C 54/14 (Close Roll 18 John) m.5, whence RLC, i, 281b. |

19 | For the medieval lore of the crane, much of it taken from Pliny, see the online resource The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages, with an image of cranes here.The cry of the crane haunts the music of both of the great Finnish composers, Sibelius and Rautavaara. |

20 | See the examples reproduced by Wild and Cassidy, above n.15. |

21 | RLC, i, 281b, and for Timsbury, in 1212 in the King’s hands, see Book of Fees, i, 81. |

22 | CRR, iii, 200, 261; iv, 21, 45; RLC, i, 131b. |

23 | Pipe Roll 16 John, 96, and cf. RLP, 96, 108b; CRR, vii, 122. |

24 | RLC, i, 276b (an order to Philip d'Aubigny, June 1216). |

25 | Patent Rolls 1216-25, 14. |

26 | Pipe Roll 3 Henry III, 178, the 50 marks being paid, apparently before Michaelmas 1221, to Thierry Teutonicus, formerly servant of John’s Queen Isabella: Pipe Roll 5 John, 88; 6 Henry III, 52; 8 Henry III, 42-3. For Eva de Gournay, CRR, ix, 28-9. |

27 | Calendar of Fine Rolls, i (1216-24), 389 no.8/349. |

28 | Roger was still living in 1220: CRR, ix, 245. By 1232, John, his son, was lord of Paulton: CRR, xiv, no.1222; Pedes Finium Commonly Called Feet of Fines for the County of Somerset, ed. E. Green, Somerset Record Society vi (1892), 74; English Episcopal Acta X: Bath and Wells. 1061-1205, ed. F. M. R. Ramsey (Oxford, 1995), no.231n.; HMC Wells, 48; A Cartulary of Buckland Priory, ed. F.W. Weaver, Somerset Record Society xxv (1909), 108-10 nos 185-9, and for his appearance in Durham charters 1222 X 1224, English Episcopal Acta, XXV: Durham. 1196-1237, ed. M. G. Snape (Oxford, 2002), nos.266, 268, 280. For Paulton, subsequently held by John’s descendants as half a knight’s fee from the lords of Chewton Mendip, see CIPM, vi, no.724. |

29 | For Richard Marsh, assuming origins unknown, see the article by R. C. Stacey, 'Richard Marsh (d. 1226', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18061, accessed 16 March 2015]. For Geoffrey and the Somerset Marisco family, see Eric St John Brooks, ‘The Family of Marisco’, Journal of the Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, lxi (1931), 22-38; lxii (1932), 50-74; F.M. Powicke, ‘The Murder of Henry Clement and the Pirates of Lundy Island’, in Powicke, Ways of Medieval Life and Thought (New York, 1971), 38-68; B. Smith, ‘Marisco, Geoffrey de (b. before 1171, d. 1245)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18060, accessed 16 March 2015]. |

30 | For the King’s itinerary here, and much else, see J.C. Holt, ‘King John’s Disaster in the Wash’, in Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government (London, 1985), 111-22, with an informative television investigation by Ben Robinson and Stephen Church, available on the BBC iPlayer website. |

Referenced in

Partridges and a Pear Tree (Features of the Month)

Partridges and a Pear Tree (Features of the Month)

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265