A Glimpse of Rebel London, May 1216

May 2015,

Following the seizure of London on 17 May 1215, the city was destined to remain in rebel hands for more than two years until its surrender to Henry III in the autumn of 1217. Events there during the intervening twenty-eight months are to a large extent obscure. We know of the attempts made by King John, both at Runnymede and after, to negotiate London's recovery.1 We know of the arrival in London before Christmas 1215 of an advance guard of Frenchmen, joined there on 2 June 1216 by Louis, son of King Philip of France.2 We can surmise that there were tensions within the city, between the native English barons and the French, between the radical canons of St Paul's and others of the city's religious, and amongst the citizens themselves (with the replacement of one mayor, Serlo the Mercer, by another, William Hardel).3 By August 1217, rumours circulated that the Londoners were about to throw off their French allegiance and proclaim obedience to the papal legate, and hence to King Henry.4 At some point during this period, the control exercised over the baronial cause by the Twenty-Five barons nominated at Runnymede yielded place to an essentially French direction of the civil war. This transfer of authority, and with it of political control over London and the rebel cause, has generally been dated to late 1215, some months before the crossing to England of Louis of France, in May 1216.5

New evidence of what happened in London during the interim emerges principally from charters. Those issued in the rebel-held city have never systematically been collected. Nonetheless, scattered instances survive, either copied into cartularies, or as single sheet originals.6 The two documents published for the first time below are further examples of this genre, significant in several respects. They survive in the library of Lincoln's Inn as late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century copies that found their way into the possession of the lawyer and legal historian, Matthew Hale (1609-1676).7 Their ultimate source is uncertain, save for the fact that they are noted as having been copied, presumably from originals, owned by a 'Mr Dee'. Dee itself is a common enough name, although it would be interesting if the 'Mr Dee' in question could be identified as the astronomer and magus, John Dee (1527-1608/9), adviser to Queen Elizabeth I. 'Dr' John Dee was a Londoner, ultimately of Welsh descent, who built up a large collection of books and manuscripts in his library at Mortlake. Despite a highly peripatetic career both in England and the German Empire, it was in London that he died in March 1609.8 Alternatively, we might be dealing with one of John Dee's sons, perhaps with the physician and alchemist, Arthur Dee (1579-1651).9 Apart from the two charters published below, the same manuscript includes transcripts of charters of King Henry II, King John and other thirteenth-century lords that appear to supply unique evidence of documents otherwise entirely lost.10

Both of our charters were issued in the name of Isabella of Gloucester. Neither of them is included in Robert Patterson's otherwise definitive edition of Isabella's acts.11 Isabella herself remains one of the more shadowy figures in the history of the reign of King John. Born at an uncertain date, perhaps as early as 1160, as the daughter of William earl of Gloucester, and hence as the great-granddaughter of King Henry I, she was betrothed (in 1176) and in 1189 married to John, Henry II's youngest son. When John succeeded to the throne ten years later, Isabella in theory became Queen of England. In practice, her failure to produce children ensured that by August 1199 her marriage to John had been annulled on the grounds of consanguinity, only three months after John's coronation as King. Thereafter, and chiefly to protect John's interest in the Gloucester estate including the city of Bristol, Isabella was kept under effective house arrest at Winchester, Bristol and elsewhere. There she remained a shadowy presence at court, even despite John's remarriage to Isabella of Angoulême.12

With the death c.1213 of Amaury of Evreux, latest male claimant to the earldom of Gloucester, Isabella's rights in the Gloucester estates acquired new significance. In January 1214, she was married off to Geoffrey de Mandeville, earl of Essex and, as a result of this union, earl of Gloucester iure uxoris. For his bride, perhaps already in her mid 50s and therefore long past child-bearing age, Geoffrey fined the enormous sum of 20,000 marks. This in turn played a significant role in Geoffrey's decision, and that of his brother William de Mandeville, to throw in their lot with the rebels of 1215. Geoffrey and William were both numbered amongst the twenty-five barons of Magna Carta. Geoffrey, however, died as the result of an accident sustained at a tournament fighting against a French knight in or near London, on 23 February 1216.13 For what happened thereafter, we chiefly depend upon a handful of charters issued by Isabella in her widowhood.14 To these the present evidences contribute a highly significant addition. In official sources, the next that we hear of Isabella comes after the rebel surrender of London in September 1217, when she was married for a third and final time, to Hubert de Burgh, the Norfolk royalist and one-time royal chamberlain. Appointed justiciar on the field of Runnymede, in royal service Hubert enjoyed a 'good' war. If his marriage was intended as reward, however, it was short lived since Isabella died within only a matter of weeks, apparently on 14 October 1217.15

What our new charters confirm is that Isabella spent at least part of the civil war in London, in the company of the leading rebel barons. Here she issued at least two confirmations to Saher de Quincy, earl of Winchester and himself a member of the baronial twenty-five, of the manors of Arrington and Orwell in Cambridgeshire. These had come to Robert earl of Gloucester, early in the twelfth century, following the forfeiture of Robert of Bellême in 1102.16 The Quincy tenancy there had been established in the time of Saher de Quincy's grandfather, another Saher (d.1190), almost certainly by his marriage to the Cambridgeshire heiress, Ascelina daughter of Pain Peverel lord of Bourn and widow of Geoffrey de Walterville (d.1162), himself steward and a regular witness to charters of Robert earl of Gloucester.17 Despite claims by others of Ascelina's kin, the manors were still assessed in 1266 as a mesne tenancy held by the earls of Winchester from the earls of Gloucester.18 The chief purpose of our two charters seems to have been to confirm Saher's tenancy in hereditary fee. This was first effected after the death of Geoffrey de Mandeville (d. February 1216) but before the issue of the second charter, dated at London on 8 May 1216. By this Isabella reduced the service owing for the two manors from two to a single knight's fee. It is worth noting that, as was so frequently the case with the rebel barons, the participants to this transaction were themselves close kin. Isabella of Gloucester was a first cousin of Margaret, Saher de Quincy's wife.19 Her sister, Amice, was married to Richard de Clare earl of Hertford, and hence wife to one member of the baronial twenty-five and mother to another (Gilbert de Clare). The Clares, as J.H. Round long ago pointed out, supplied links of kinship to a large number of the twenty-five, including both Robert fitz Walter and Saher de Quincy.20

So far, then, our charters supply an interesting insight into the ties that bound the rebels. But their significance extends beyond this. To begin with, they reveal Isabella of Gloucester, John's former queen, occupying a prominent and apparently honoured place at the heart of rebel-held London. For the King's former wife to have so altered her allegiance should surely remind us of the heady days of the 1170s, when Eleanor of Aquitaine, John's mother, had played a leading role in the great rebellion against her husband, King Henry II. Even more significantly, and here considering not only the principal parties to these charters but their witnesses, we find, as late as May 1216, a full year after the rebel seizure of London and nearly a year since Runnymede, no less than ten of the twenty-five barons of June 1215 still resident in London, still operating together as a rebel elite: Saher de Quincy earl of Winchester, Richard de Clare earl of Hertford, William de Mandeville earl of Essex, Robert de Vere earl of Oxford, Robert fitz Walter, William Marshal the younger, Gilbert de Clare, William of Huntingfield, William de Lanvallay, and Isabella herself as representative of Geoffrey de Mandeville.

The pattern of witnessing by these men is itself significant. We might note, for example, that in the first of our new charters the name of Robert fitz Walter appears at the head of the witness list, above that of an earl, William de Mandeville, albeit a self-styled earl (since William can have had no royal warrant for claiming succession to his late brother, Geoffrey de Mandeville, just as Geoffrey and Isabella's claims to be earl or countess of both Essex and Gloucester seem to have been advanced without necessarily obtaining approval from the King).21 The names of two others of the witnesses to the first charter, William of Huntingfield and William de Lanvallay, are separated from those of their fellow members of the twenty-five, being placed after the names of three other prominent rebels, Roger de Cressy, Robert Gresley and Robert Marmion. Even in the second charter, although the name of Robert fitz Walter is demoted below that of the earls, including his kinsman Richard de Clare, earl of Hertford, and although William of Huntingfield is promoted to sit next in the witness list to his fellow members of the twenty-five, the name of William de Lanvallay still appears far down the witness list, divided from the rest of the twenty-five by the names of Robert Gresley, William de Ros, Robert of Ropsley, John of Bassingbourne and Roberto de Percy.

As this implies, there may well have been a resettling of the pecking order amongst the leading rebels since the constitution of the twenty-five a year earlier. The ranking of the rebel earls may itself have produced tensions. Certainly, the ranking of earls seems to have been a long-established necessity.22 In our second charter, we find the order Hertford, Essex, Oxford. In other letters issued in the name of the twenty-five, including the 'London Treaty' negotiated with the King in the summer of 1215, we find the order Hertford, Essex, Norfolk, Winchester, Oxford and Hereford, or (in June 1215) Hertford, Gloucester and Essex, Norfolk, Winchester, in both instances headed by the name of Robert fitz Walter, in the 'London Treaty' credited with title as 'Marshal of the Army of God and Holy Church in England'.23 By the end of September 1215, by contrast, we find the order Essex and Gloucester, Winchester and only then Richard de Clare earl of Hertford, suggesting that earl Richard's seniority was largely honorific and reflected little practical command over the baronial army.24

There are other points of interest to our witness lists. Besides the twenty-five, we find the names of eleven other men, the majority of them prominent rebels. Some were already malcontents before the seizure of London in May 1215 (including Roger de Cressy, rebel sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk). Others had defected to the rebel cause only later, including Robert of Ropsley who, at Runnymede in June 1215, was named as one of the royalist barons who had counselled the issue of Magna Carta. John of Bassingbourne was another royal servant who had since thrown in his lot with rebellion. It is also noticeable that although our witness lists include a number of men from the north (Robert Gresley, William de Ros and Robert de Percy), it includes none of the northern members of the twenty-five (Eustace de Vescy, William de Mowbray, Roger de Montbegon, Robert de Ros, John de Lacy, Richard de Percy). Was it that these 'Northerners' had by this time returned home, leaving London and the rebel cause to the supervision of a knights and barons drawn principally from southern England and in particular from Essex and East Anglia? Out of a total of eighteen witnesses to Isabella's charter, only two (William of Knapwell and Nicholas of Kennet) are not immediately familiar. Both were Cambridgeshire men, Nicholas holding Kennet of the earls Warenne, William holding land at Shudy Camps from Richard de Montfichet (another of the twenty-five barons of Magna Carta, whose lands here marched with those of the Vere earls of Oxford at Castle Camps).25 Nicholas, who had served in 1209 as royal constable of Bolsover, faced confiscation as a rebel at the time of the siege of Rochester in November 1215.26 He was eventually restored to his property in Kent, Worcestershire, Norfolk and Suffolk, Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire in November 1217, at much the same time that William of Knapwell was restored to a more modest estate in Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire.27 The presence of these two men as witnesses, meanwhile, confirms the essentially East Anglian focus of the present transactions.

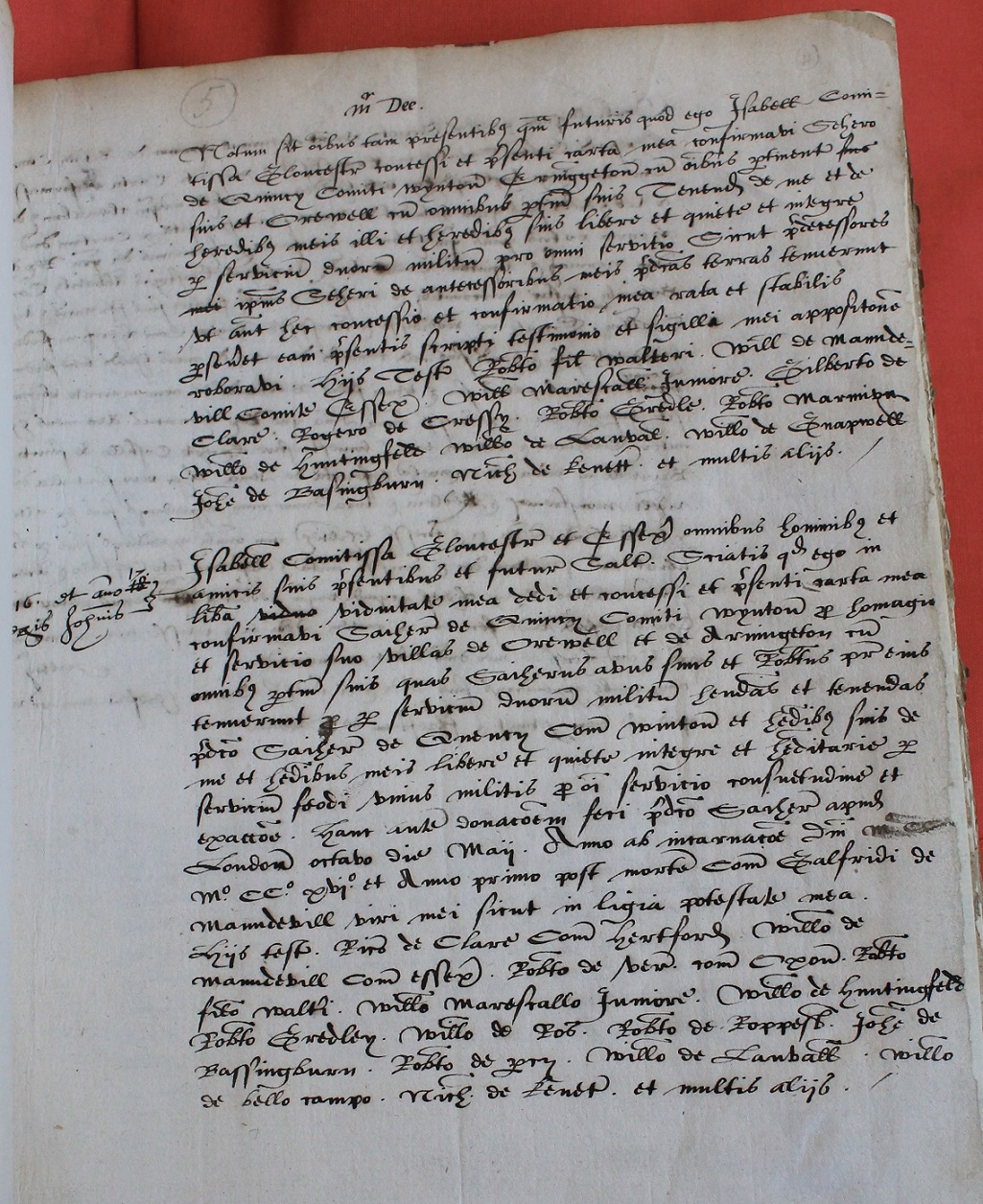

1. Notification by Isabella countess of Gloucester of her grant to Saher de Quincy earl of Winchester of Arrington and Orwell (Cambridgeshire) for the service of two knights' fees as Saher's predecessors were accustomed to render to Isabella's ancestors. [March 1216 X March 1217]

B = London, Lincoln's Inn ms. Hale 100 fo.4r, merely marked 'Mr Dee', s.xvii.

Notum sit omnibus tam presentibus quam futuris quod ego Isabell(a) comitissa Gloucestr' concessi et presenti carta mea confirmaui Schero de Quincy comiti Wynton' Erninggeton' cum omnibus apertinent(iis)a suis et Orewell cum omnibus pertin(entiis) suis tenend(os) de me et de heredibus meis illi et heredibus suis libere et quiete et integre per seruicium duorum militum pro omni seruitio sicut bpredecessoresb ipsius Scheri de antecessoribus meis predictas terras tenuerunt. Ut autem hec concessio et confirmatio mea rata et stabilis perseueret, eam presentis scripti testimonio et sigilli mei appositione roboraui. Hiis test(ibus): Roberto fil(io) Walteri, Will(elmo) de Maundeuill comite Essex', Will(elmo) Marescall(o) iuniore, Gilberto de Clare, Rogero de Cressy, Roberto Gredle, Roberto Marmiun, Will(elm)o de Huntingfeld, Will(elm)o de Lanual, Will(elm)o de Gnapwell, Ioh(ann)e de Bassingburn, Nich(olao) de Kenett' et multis aliis.

2. Notification by Isabella countess of Gloucester of her grant to Saher de Quincy, earl of Winchester, in her free widowhood, of the vills of Arrington and Orwell that Saher's father, Robert, and Saher's grandfather, Saher, held for the service of two knights, now to be held in hereditary fee for the service of a single fee. (London, 8 May 1216)

B = London, Lincoln's Inn ms. Hale 100 fo.4r, merely marked 'Mr Dee', s.xvii.

Isabell(a) comitissa Gloucestr' et Essex' omnibus hominibus et amicis suis presentibus et futur(is) salutem. Sciatis quod ego in cliberac viduitat(e) mea dedi et concessi et presenti carta mea confirmaui Saiher(o) de Quincy comiti Wynton' pro homagio et seruicio suo villas de Orewell et de Arningeton cum omnibus pertin(entiis) suis quas Saiherus auus suus et Robertus pater eius dtenueruntd per seruicium duorum militum habendas et tenendas predicto Saiher(o) de Quency com(iti) Winton' et heredibus suis de me et heredibus meis libere et quiete, integre et hereditarie per seruicium feodi unius militis pro omni seruicio, consuetudine et exactione. Hanc autem donacionem feci predicto Saiher(o) apud London, octauo die Maii, anno ab incarnacione edominie m.cc.xvi. et anno primo post mortem com(itis) Galfridi de Maundeuill viri mei sicut in ligia potestate mea. Hiis test(ibus): Ricardo de Clare com(ite) Hertford, Will(elm)o de Maundeuill com(ite) Essex', Roberto de Ver' com(ite) Oxon', Roberto fil(i)o Walteri, Will(elm)o Marescallo iuniore, Will(elm)o de Huntingfeld, Roberto Gredley, Will(elm)o de Ros, Roberto de Roppesl', Ioh(ann)e de Bassingburn, Roberto de Percy, Will(elm)o de Lanuall', Will(elm)o de Bellocampo, Nich(olao) de Kenet et multis aliis.

aB inserts suis, cancelled bB inserts mei, cancelled cB inserts vidua.., cancelled dB inserts per, cancelled eB inserts m.cc., cancelled

1 | H.G. Richardson, ‘The Morrow of the Great Charter’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, xxviii (1944), 424–5; J. C. Holt, Magna Carta (Cambridge, 1992), 262-6, 486-8, 490–1. |

2 | Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria, ed. W. Stubbs, 2 vols. (London, 1872-73), ii, 225-6, 228-30 |

3 | For the mayors, C.N.L. Brooke and G. Keir, London 800-1216: The Shaping of a City (London, 1975), 376. For the patchy enforcement of the interdict pronounced against the city in May 1216, see The Letters and Charters of the Legate Guala Bicchieri, Papal Legate in England, 1216-1218, ed. N. Vincent (Woodbridge, 1996), 39 no.52n. |

4 | Letters of Guala, ed. Vincent, p.xlii, citing Recueil des historiens des Guales et de la France, ed. M. Bouquet and others, 24 vols. in 25 (Paris, 1738-1904), xviii, 240. |

5 | N. Vincent, 'The Twenty-Five Barons of Magna Carta: An Augustinian Echo?', Rulership and Rebellion in the Anglo-Norman World, c.1066-c.1216: Essays in Honour of Professor Edmund King, ed. P. Dalton and D. Luscombe (Farnham, 2015), 234-5. |

6 | For instance TNA E 40/1476 (William Brito to the canons of Holy Trinity London, witnessed by William Hardel as mayor); The Cartulary of Holy Trinity Aldgate, ed. G.A.J. Hodgett, London Record Society vii (1971), 204 no.1011; Cartulary of St Bartholomew's Hospital, ed. N.J.M. Kerling (London, 1973), 73 no.695 (Geoffrey de Mandeville as earl of Essex and Gloucester to Walter son of Algar), 64 no.583 (Alexander of Norfolk witnessed by William Hardel as mayor of London), and cf. 59 no.531 (issued in September 1217, following the battle of Lincoln); Earldom of Gloucester Charters: The Charters and Scribes of the Earls and Countesses of Gloucester to A.D. 1217, ed. R.B. Patterson (Oxford, 1973), 110-11 no.114 (from TNA E 40/2385, Isabella countess of Gloucester to Holy Trinity London, witnessed by William de Mandeville as earl of Essex, and by Master Elias of Dereham); BL Harley Charter 43.A.56, whence Starrs and Jewish Charters Preserved in the British Museum, ed. I. Abrahams, H.P. Stokes and H.M.J. Loewe, 3 vols. (London, 1930-2), i, 26-9 no.1181, ii, 114-31 (Abraham son of Muriel of London, sale to Geoffrey de Mandeville earl of Essex and Gloucester of property in West Cheap for 35 marks, witnessed, amongst others, by Serlo the Mercer mayor of London, William de Mandeville and William of Howbridge, the property then conveyed by Geoffrey de Mandeville as earl of Essex and Gloucester, to Gilbert de Waletun, in a charter witnessed by William de Mandeville and Serlo the Mercer as mayor, TNA E 40/1988, also in Cartulary of Holy Trinity, 105 no.527), and cf. the 'English' charters of Prince Louis issued in 1216: Étude sur la vie et le règne de Louis VIII (1187-1226), ed. C. Petit-Dutaillis (Paris, 1894), 120 n.4, 511 no.1 (the first from Paris, Bibliothèque nationale ms. Pièces Originales 892 (formerly ms. francais 27376) no.90, as printed by H. Stein, 'Chartes inédites relatives à la famille de Courtenay et à l'abbaye des Echarlis', Annales de la Société Historique et Archéologique du Gatinais, xxxvi (1922), 154-5 no.15, having earlier been printed without attribution, as an examination exercise, in Bibliothèque de l'Ecole des Chartes, xxxviii (1877), 375-6; the second from BL ms. Harley Charter 43.B.37, dated at the siege of Hertford, 21 November 1216, witnessed, amongst others, by Saher de Quincy, Robert fitz Walter and Master Simon Langton). |

7 | London, Lincoln's Inn ms. Hale 100, briefly listed, including an abstract of the two charters published below, by Joseph Hunter, Three Catalogues; describing ... the Manuscripts in the Library of the Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn (London, 1838), 336-9 (there numbered ms.93/100), dated to the time of Elizabeth, with suggested identification of 'Mr Dee' as 'Dr John Dee'. |

8 | R.J.Roberts, ‘Dee, John (1527–1609)’,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn., May 2006) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7418, accessed 31 May 2015] and for Dee's interest in, and collection of British historical antiquities, see idem, ‘John Dee and the matter of Britain’, Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (1991), 129–43; idem, with A. G. Watson, John Dee's Library Catalogue (London, 1990); Glyn Parry, The Arch-Conjuror of England: John Dee (New Haven, 2011), 39-41, 270-1. Two of his manuscripts, containing charter materials for Glastonbury Abbey and Rochester Cathedral Priory, passed into the collection of Sir Robert Cotton: G.R.C. Davis, Medieval Cartularies of Great Britain and Ireland, 2nd edn. by Claire Breay and others (London, 2010), 91-2 no.458, 165 no.821. |

9 | J.H. Appleby, ‘Dee, Arthur (1579–1651)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn., Jan 2008) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7415, accessed 31 May 2015]. Various of Matthew Hales' manuscripts were inherited from the lawyer John Selden (1584-1654), but ms. Hale 100 does not seem to be amongst them: Papers of British Antiquaries and Historians, Historical Manuscripts Commission Guides to Sources for British History 12 (London, 2003), 183. |

10 | London, Lincoln's Inn Library ms. Hale 100 fos.4v (a charter of Henry de Bohun earl of Hereford to King John, otherwise known from RC, 61b), 5r-6r (from the collections of John FitzRowland, dated 1574, copying charters of Henry II to Geoffrey fitz Peter, Elias de Pidele to the same, Matilda de Mandeville countess of Essex, after 1226/7 to Matilda d'Oilly, Geoffrey de Wytefeud to John fitz Geoffrey, and Henry d'Oilly to the same). |

11 | Earldom of Gloucester Charters, ed. Patterson. |

12 | See in general, R. B. Patterson, ‘Isabella, suo jure countess of Gloucester (c.1160–1217)’,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edn., Oct 2005) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/46705, accessed 31 May 2015]. For her presence, alongside Isabella of Angoulême, at Marlborough, see N. Vincent, 'Isabella of Angoulême: John's Jezebel', King John: New Interpretations, ed. S.D. Church (Woodbridge, 1999), 196-7. |

13 | The Complete Peerage, ed. G. E. Cockayne, rev. V. Biggs, H. E. Doubleday, Lord Howad de Walden and G. H. White, 12 vols. in 13 (London, 1910-57), v, 129, citing Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 164; Wendover, in Paris, Matthaei Parisiensis, Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard, 7 vols. (Rolls Ser., 1872–83), ii, 650; Radulphi de Coggeshall Chronicon Anglicanum, ed. J. Stevenson (Rolls ser., 1875), 179, and cf. Cartulary of Holy Trinity, 137 no.701a, for what may have been a mortuary gift by his brother, William de Mandeville, following Geoffrey's burial at Holy Trinity Aldgate. |

14 | Earldom of Gloucester Charters, ed. Patterson, nos. 76, 114, 141-50, and for charters issued by her as countess of Gloucester and Essex apparently during the lifetime of Geoffrey de Mandeville, nos. 4, 9, 140, with Isabella's seal attached to nos. 140, 144-6 (Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales mss. Penrice and Margam 113, 113c, 2042-3, pointed oval, a standing female figure, forearms extended with long hanging sleeves, a flower or fleur-de-lys in her right hand, a bird in her left hand, legend: +SIGILLVM ISABEL' COMITISSE GLOECESTRIE ET MORETUNE, i.e. the seal used by her from 1189 to 1199 as countess of Mortain, counterseal, an antique intaglio, oval, a helmeted bust to the right between two figures of Nike, an eagle below rising between two standards, legend: +EGO SV' AQILA CVSTOS D'NE MEE, cf. Plate XXXI d and f. |

15 | GEC, Complete Peerage, v, 129-30, citing the Canterbury obit list in London, Lambeth Palace Library ms. 20, 'II. Idus Octobris. Obiit Isabella comitissa'. For what may well have been a deathbed grant by Isabella, with title as countess of Gloucester, granting the monks of Canterbury £10 of land in her manor of Petersfield (Hampshire), witnessed by Hubert de Burgh and other members of the De Burgh household, see Canterbury Cathedral Archives ms. D. & C. Register B fo.404r. |

16 | For what follows, see especially VCH Cambridgeshire, v, 141, 242-3, and cf. W. Farrer, Feudal Cambridgeshire (Cambridge, 1920), 236-8, 254-5. |

17 | For Geoffrey de Waterville/Walterville as witness, see Earldom of Gloucester Charters, ed. Patterson, nos. 6, 70, 83, 95, 110. |

18 | CRR, xi, 417, xii, 24; Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, i, p.199. |

19 | Isabella's mother Hawise, and Margaret's father Robert earl of Leicester (d.1190) were both the children of Robert earl of Leicester (d.1168). |

20 | J. H. Round, 'King John and Robert Fitzwalter', English Historical Review, xix (1904), 707-11, continuing work first published by Round in his Feudal England (London, 1895), 475, 575, and idem., 'The Fitzwalter Pedigree', Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society, n.s. vii (1900), 329-30 |

21 | As Geoffrey's wife and widow, Isabella continued to use the seal that she had first employed as countess of Mortain and Gloucester, whilst married to the future King John from 1189 to 1199 (above n.13). As earl of Essex and Gloucester, Geoffrey sealed his charters with a seal that he had apparently carried before his promotion to comital status: Earldom of Gloucester Charters, ed. Patterson, nos. 93, 139 (from Hereford Cathedral Library charter no.2304, and Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales ms. Penrice and Margam 113b), round, a shield of arms with a large central cross, quarterly, legend: +SIGILL' GALFRIDI DE MAVNDEVIL', cf. Plate XXXI f. |

22 | N. Vincent, ‘Did Henry II Have a Policy Towards the Earls?’, War, Government and Aristocracy in the British Isles, c.1150-1500. Essays in Honour of Michael Prestwich, ed. C. Given-Wilson and others (Woodbridge, 2008), 1-25. |

23 | Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 490, and cf. London, Lambeth Palace Library ms.1213 p.194. |

24 | Holt, Magna Carta (1992), 499-500 nos 15-16, in both instances with Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford, as sole witness. |

25 | VCH Cambridgeshire, vi, 50, 57; x, 461; Farrer, Feudal Cambridgeshire, 67-9, 148. |

26 | RLC, i, 234, 234b, 235b, 237b, 240, 296b; RLP, 89. |

27 | RLC, i, 325, 375, 375b. |

Referenced in

John and the siege of Rochester: week four (The Itinerary of King John)

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265