Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta (1923-2015)

July 2015,

On Monday 15 June 2015, various members of our project team were present at Runnymede for Magna Carta's great 800th celebrations.1 The meadow where we gathered (very early in the morning, in order that the Queen could attend the Garter ceremony in Windsor later that day) has long been the property of the National Trust. What transpired there on 15 June was described to me aptly enough, by a colleague, as a wonderfully English combination of village fète and fascist flag rally. It is widely known that Runnymede has belonged to the National Trust since its sale by the crown in 1929 (not officially transferred to Trust ownership until 1931). The circumstances of its acquisition have been investigated by Ben Cowell, and are currently the subject of further enquiry by Steven Franklin.2 The general understanding is that the meadow, threatened with piece-meal sale and redevelopment since the early 1920s, was in 1929 'saved' for the nation by Lady Fairhaven, widow of the late Urban Hanlon Broughton (1857-1929). Even as it stands, this story is a complicated one. New evidence, set out below, suggests that it may be more complicated still.

Urban Broughton, son of a railway manager, was schooled in Wrexham and trained at as a sewage engineer at the University of London. In the 1890s, he successfully brought modern sanitation to the town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts. There his fortunes were transformed when he met and married Cara Leland Duff, the recently widowed daughter of Henry H. ('hell-hound') Rogers (1840-1909). Rogers, a paraffin salesman who had risen on the coat-tails of John D. Rockefeller, was by this time a multi-millionaire director of Rockefeller's Standard Oil Trust. Following a buccaneering career as president of the Utah Consolidated Mining Company and having succeeded his father-in-law as president of the Virginian Railway Company, Urban Broughton returned to England and sat from 1915 to 1918 as Conservative MP for Preston. In 1928 he purchased Ashridge House in Hertfordshire, the former seat of the earls of Bridgewater. This he presented to the Conservative Party as a memorial to his former party leader, Andrew Bonar Law (d.1923), a Canadian-born promoter of new men in the Conservative interest. The Ashridge estate, distinct from the house, had been gifted to the National Trust as early as 1921, so that there was already a National Trust connection here.

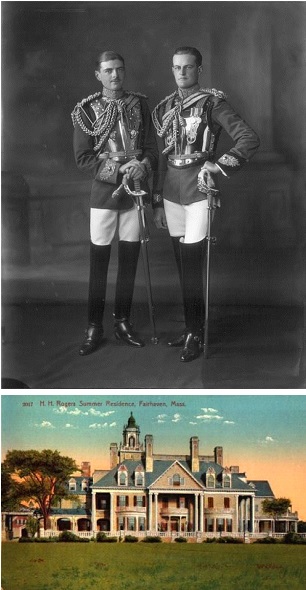

In 1928, Broughton was promised a peerage, but he died in January 1929, before this promotion had been achieved. On the advice of the Conservative Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, King George V was persuaded to grant the style and title of Lady Fairhaven to Broughton's widow as if her husband had been created Baron Fairhaven. It was at precisely this time that Lady Fairhaven, with her six-storey town house at 37 Park Lane, Mayfair, and a country mansion at Park Close near Egham, stepped in to secure the future of nearby Runnymede.3 Lady Fairhaven's son, Urban Huttleston Rogers Broughton (1896-1966), was meanwhile recognized as 1st Baron Fairhaven of Lode in the County of Cambridge. Since 1926, he and his younger brother, Henry Rogers Broughton, had been joint owners of the Anglesey Abbey estate at Lode, convenient for Newmarket where their father owned the Barton Stud. When it became clear that the 1st Lord Fairhaven would have no issue, a second barony was created, in 1961, to allow descent to his younger brother who succeeded, in 1966, as 2nd Lord Fairhaven of Anglesey Abbey. At the time of writing, Ailwyn Henry George Broughton (b.1936), the son of this younger brother and grandson of Urban Hanlon Broughton, enjoys the peerage created in 1961, as 3rd Lord Fairhaven.

With apologies for the length and complexity of this descent, what I hope will be apparent is that the Fairhaven peerage was a peculiar creation, floating upon sewage and petroleum and established for the offspring of one of the world's richest men. Without necessarily implying that the saving, first of Ashridge (1928), and then of Runnymede (1929) functioned as purchase price for the barony, it is certainly remarkable that these transactions, both closely associated with the National Trust, should have preserved, in the first instance for the Conservative Party, in the second for the nation, two of the most iconic sites in southern England. In Maundy Gregory and Lloyd George's golden days, baronies remained a highly marketable commodity.4 After the purchase of Runnymede, relations between the Trust and the Broughton family were close but never especially warm. James Lees-Milne, for example, has left a less than flattering portrait of the 1st Lord Fairhaven who in 1941 added Kirtling Tower near Newmarket to his already extensive collection of country houses.5 So it is that we come to the situation of Runnymede in the 1920s, during the period before the Fairhaven purchase and the site's transfer to the National Trust.

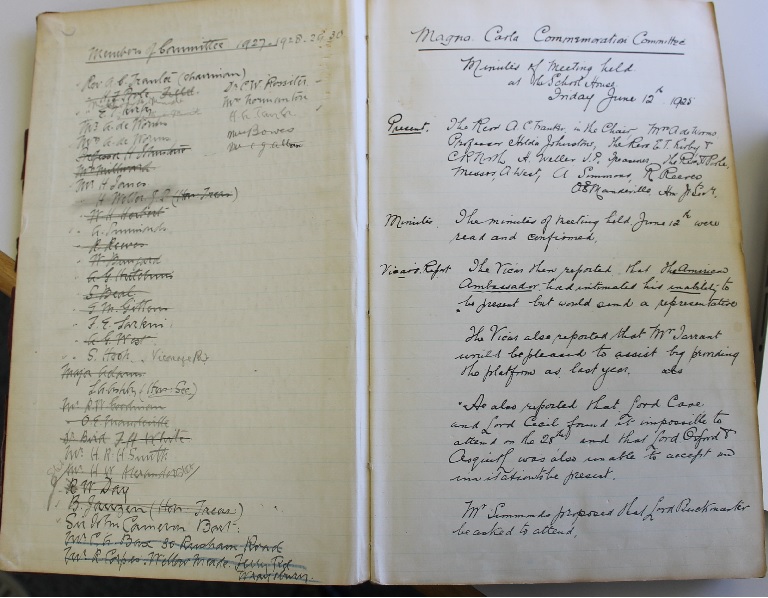

There survives in the Surrey Archives Centre at Woking a minute book of the 'Magna Carta Commemoration Committee', covering the period from 1925 to 1933.6 This survival is fortuitous, since so many other records of Egham parish church seem to have been lost or never to have been deposited. Particularly unfortunate here is the loss of the parish service registers from 1906 onwards. Elsewhere, such registers can be used to assess the depth of interest in Magna Carta commemorations. At Little Dunmow in Essex, for example, the chief seat of the Magna Carta baron Robert fitz Walter, Katharine Schofield has revealed that whereas attendance at Sunday morning services generally hovered around 70, on 13 June 1915, the seven hundredth anniversary of Magna Carta, marked by a special commemoration service and the launch of a Fitzwalter Memorial Fund, more than 145 people crammed into the church.7 By contrast, during the depths of the First World War, the anniversary was only sparsely celebrated elsewhere. The demand by the Church Reform League, issued in May 1915, that its followers lobby for 'a reasonable measure of self-government' for the Anglican Church, in commemoration of clause 1 of Magna Carta, seems to have fallen on deaf ears.8 So too did much else in the charter, in effect suspended both in letter and spirit by the 1914 Defence of the Realm Act. The proposal of the Royal Historical Society, launched in January 1914, to stage full-scale anniversary celebrations, had been abandoned soon after the outbreak of hostilities. In May 1915, the Lusitania was sunk by German U-boat and London suffered its first aerial bombardment. Instead of celebrating the birthday of Magna Carta, in June 1915 the Royal Historical Society arranged rather more opportune lectures, by Ernest Baker, on 10 June, on 'The Expansion of Germany since 1890', and by Colonel E.M. Lloyd, on 18 June, describing 'Some Episodes of Waterloo as Illustrations of Historical Evidence'. Not until late October did the Society agree to a lecture by Professor McKechnie, the great Glasgow commentator on Magna Carta, eventually delivered on 27 November 1915 and published, together with other Magna Carta Commemoration Essays, late in 1917.9

At Runnymede itself, there was no commemoration in 1915 to mark the 700th anniversary. This despite the fact that, since at least 1907, the International Magna Carta Day Association had been established by the American, J.W. Hamilton to secure the observance of 15 June throughout Great Britain, the USA and the British Dominions 'to strengthen the ties that bind them together'. 10 Hamilton's Association, like other Anglophone co-operative societies, not least the English-Speaking Union founded in 1918 by (the Ulsterman) Sir Evelyn Wrench, had an agenda planted deep in a sense of Anglophone superiority, combined with the fear that without mutual support, the Anglo-Saxon peoples would fall prey to enemies and inferiors.11 It was in this same spirit of racial interdependence that, in 1914, Sulgrave Manor in Northamptonshire, the Washington family seat, had been purchased and restored as a public monument to Anglo-American solidarity.12 It was with similar thoughts in mind that, addressing a rally of the English-Speaking Union in the Albert Hall on 4 July 1918, Winston Churchill, described the American Declaration of Independence as, after Magna Carta and the 1689 English Bill of Rights, 'the third great title-deed on which the liberties of the English-speaking people are founded'. In this reading, Magna Carta retained both its mystique and its precedence.13

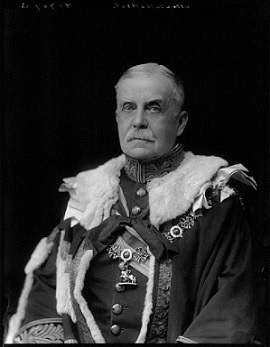

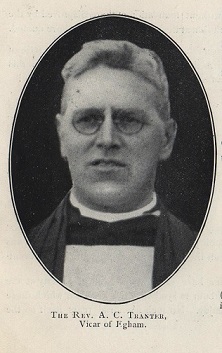

The minute book that survives at Woking is, on the face of things, a record of far less heroic endeavours than either the ESU or the International Magna Carta Day Association. Here we are definitely in the parish pump world of Albert Herring and Lady Billows. The Magna Carta Commemoration recorded here seems to have begun in 1923, in part through the efforts of Helena Normanton (1882-1957), henceforth the Committee's London secretary and a formidable campaigner, called to the bar in 1922 as only the second woman barrister in the history of the English legal profession.14 The other principal mover was the vicar of Egham, Albert Cecil Tranter. Ordained priest in Sydney Australia in 1907, Tranter served as curate (1909) and then as vicar (1918) of Egham for nearly forty years through to his retirement in 1947. It was he who chaired the local meetings of the Magna Carta Commemoration and it was he who devised the peculiar combination of liturgy and public rally that the Commemoration involved. As its figurehead and President, the committee enjoyed the support of Robert Wynn Carrington, 1st Marquess of Lincolnshire (1843-1928), a Liberal politician and one-time Governor of New South Wales (1885-90). Lord Lincolnshire, already eighty at the time of the Commemoration's first meeting, played thereafter a ceremonial, though as we shall see not entirely insignificant role in the history of Runnymede.

Our minute book begins only in 1925, the third year of the Runnymede Commemoration, but with evidence that the basic form of the ceremony had been in place since 1923.15 A number of elements went into these events. First, on a Sunday close to the 15 June anniversary of Magna Carta, a procession was held from Egham to Runnymede, involving the Egham town band, civic dignitaries, scouts, girl guides, the friendly societies and as large a crowd of day-trippers as could be assembled by advertising locally and in London clubs and hotels. After a religious ceremony involving hymns and, perhaps in the very earliest years, a recitation of select clauses from Magna Carta, the gathering would be addressed by a significant public figure. From the very outset, it was the recruitment of this celebrity that posed the chief obstacle to the Commemoration's success. In addition to the jamboree at Runnymede, in its earliest years the Committee dispatched a wreath, woven with flowers gathered at Runnymede, to be placed on the tomb of Stephen Langton in Canterbury Cathedral, on or around 15 June. An annual telegram was sent to King George V pledging loyalty, to which in some (perhaps in all) years, the King replied with his own message of thanks. In 1925, 1926, and perhaps in other years, there was also a 'pageant', held on a date close to but not identical with that of the Commemoration, including local school children and, one assumes, a great deal of dressing up.16

Putting aside the minutiae of local politics, a number of themes emerge from the Committee's activities. The first is that the Commemoration was a far from negligible event. For its meeting of 1925, for example, 2000 hymn sheets were supplied.17 In 1929, nearly 5000 people are said to have attended.18 In 1927, by contrast, in a heavy downpour and amidst complaints that local children had not be kept under 'proper control', costs exceeded receipts by £7.19 Secondly, with its success depending very largely upon the invited speaker, there was near constant disappointment that the Committee was unable to secure the services of really first -rate celebrities. The minutes are full of the names of those (in 1925, for example, the American Ambassador, the Lord Chancellor, Lord Cave, Lord Robert Cecil, and Herbert Asquith, now Lord Oxford and Asquith) who replied to their invitations with apology or excuse.20 In 1931, there was briefly excitement that Sir John Simon, past and future Home Secretary, had accepted an invitation, dashed when Simon defected from Lloyd-George's Liberal Party and, as a last-minute substitute, instead sent to Runnymede the rather less well-known Edward Marjoribanks, Conservative MP for Eastbourne.21 The reluctance of the great and good to trek out to the Thames can be explained by the way in which the committee too often left it until April or May to approach its celebrity guests. As a result, the list of speakers is not a particularly distinguished one:

1924 J.H. Whitley M.P. (Speaker of the House of Commons)

1925 James Henry Darlington (Episcopalian Bishop of Harrisburg

Pennsylvania)

1926 Lord Hewart (Lord Chief Justice)

1927 Sir Ernest Wild K.C. (Recorder of the City of London)

1928 Baroness Ravensdale (eldest daughter of Lord Curzon)

1929 Dr Draper (Master of the Temple Church)

1930 Captain E.A. Fitzroy M.P. (Speaker of the House of Commons)

1931 Edward Marjoribanks M.P.

1932 [Abandoned for lack of a speaker]

1933 Leo Amery M.P.

Alongside these disappointments, the Committee was dogged by further problems. The first, and perhaps most persistently resented of these, was Mr Hamilton, Secretary of the International Magna Carta Day Association. As early as 1925, we find Hilda Johnstone, Professor of Medieval History at Royal Holloway College, at pains to record that the purpose of the Egham committee was 'to commemorate the granting of Magna Carta on the site where the event occurred and that in so doing it is acting independently of any other body'.22 As London Secretary, Mrs Normanton went to considerable lengths to repudiate any claim that the International Association should have responsibility for the Commemoration.23 In 1926, there was much discussion of the best means of preventing Mr Hamilton from making any sort of address.24 So much so that the venerable authority of Lord Lincolnshire was invoked to quash any suggestion that Hamilton might move a vote of thanks.25 The following year, there was a similar repudiation both of Hamilton and of any other 'trans-Atlantic bodies'.26 In 1929, amidst efforts to reconstitute the Commemoration as part of a wider 'Magna Carta Society', Mrs Normanton referred not only to Hamilton's attempts to claim undue credit for the annual celebrations but to others of his unwelcome interventions: the 'unpleasantness' he had caused over the dispatch of a wreath to the tomb of Stephen Langton, and the dislike felt for him by the organizers of Magna Carta celebrations in Bury St Edmunds.27 As late as 1930, when a false rumour circulated that Stanley Baldwin was to be present at the Runnymede Commemoration, there were some on the Committee inclined to blame this on what was disparagingly described as 'the Hamilton faction'.28

Apart from the nuisance of Mr Hamilton, there were other points of tension. Not everybody approved of the religious aspect of the service. After the mid 1920s, the bandsmen of the Staines Salvation Army refused to play alongside the Egham town band, and the Egham players were deemed in need of more time to master the hymns. As early as 1925 there are signs that the reading out of parts or the whole of Magna Carta, apparently attempted at earlier commemorations, had occasioned confusion or distress.29 There were protests against the activities of a local flying club.30 The dispatch of a wreath to Langton's tomb was effectively abandoned after 1926, when it was said to have met with a 'somewhat tepid' reception from the Dean of Canterbury. The appearance of Edward Marjoribanks as substitute speaker in 1931 was followed, less than a year later, by tragedy when Marjoribanks shot himself dead, in the billiard room of his stepfather, Lord Hailsham, the former Conservative Lord Chancellor.31 As early as 1927, certain unspecified slurs against the Magna Carta movement, published in the personal columns of the Morning Post, necessitated a response, published at the not inconsiderable cost of £1 17s. 6d.32 As a former resident of Australia, the Reverend Tranter was naturally keen to commemorate the connection between Runnymede and the Dominions, flying the Dominion flags at successive commemorations. He nonetheless had trouble with the flag of the Irish Free State, which in 1926, with typical Hibernian promptness, failed to arrive until a day after the service had been held.33 There were also ongoing and only partially concealed tensions within the organization, especially between those locally who favoured a religious ceremony, and those in London, Mrs Normanton amongst them, who craved something more overtly political. From an early date, these tensions surfaced over a related issue: the bid by the Committee to assist with the purchase of the site of Runnymede, since the early 1920s threatened with piece-meal disposal by the government land agency.

As early as March 1926, the Committee was discussing the possibility of 'saving' the site, through an approach to the two or three principal owners of the meadows between Cooper's Hill boathouse and 'the first bend in the river'.34 In May that year, it was agreed that such a purchase would require the setting up of a special sub-committee.35 By 25 May, approaches had been made to the land agents, Carter Jonas, to commission a survey of ownership on the meadow. The veteran Lord Lincolnshire took a personal interest in these developments.36 On 10 June, under his chairmanship, and meeting not at Egham but at his Lordship's London residence at Princes Gate, a rump of the Committee interviewed Mr Jonas over the vexed problems of manorial right, copyhold, and the possibilities of moving an Act of Parliament to retain the meadow in permanent public use.37 Those not present at this meeting clearly resented their exclusion.38 Even so, following Lord Lincolnshire's advice, and despite failing to recruit Stanley Baldwin's as their next year's speaker, the Committee put out feelers to the Mayor and Corporation of London, deemed vital to the scheme's financial prospects.39 It was through Lord Lincolnshire's endeavours that the National Trust seems first to have become involved in negotiations. By December 1927, the Trust's Secretary, Mr Hamer, had expressed his enthusiasm and Lord Lincolnshire was proposing to introduce a bill to the House of Lords to allow for the site to be purchased and rescheduled as a royal park.40

But his Lordship was now in failing health. In 1928, he died. Despite his endeavours and those of Mrs Normanton to transform the Committee into a national 'Society', at his death, Lord Lincolnshire left nothing more than an ambition that his surviving daughter, Lady Nunburnholme, might assist with the endowment necessary for any land purchase.41 It was only at this stage in proceedings that the American-born Lady Fairhaven seems to have become involved. At the Commemoration, on 23 June 1929, before an audience estimated at 5000 people, the Reverend Tranter announced his hope that the site would very soon be saved. Salvation was duly reported in the Times, on 18 December 1929, with the announcement that Lady Fairhaven had purchased all 182 and a half acres of land in Egham beyond Magna Carta Island as far as the Bells of Ouseley with the intention that this be gifted to the National Trust.42

With the purchase and the establishment of a committee of management for the meadow, the Reverend Tranter was co-opted onto this new body under the chairmanship of Lord FitzAlan.43 In fact, however, as Steven Franklin has recently discovered, the vicar's role went much deeper than this. The deeds of purchase for 115 acres of land at Runnymede, dated 14 December 1929 and lodged with the National Trust, name two individuals as purchasers of the site: the prominent London solicitor, Sir Reginald Ward Edward Lane Poole (1864-1941), and A.C. Tranter, vicar of Egham. Presumably this was a legal fiction, with Poole and Tranter acting merely as trustees for the £4,800 advanced, we must assume, by Lady Fairhaven to buy out the various previous owners of the site.

As for the Magna Carta Commemoration Committee, the Fairhaven purchase marked what in hindsight appears to have been the beginning of the end. Despite inviting on to their committee two local residents, Mr Bax and the rather too morbidly named Mr Corpes, prominent in the Ancient Order of Buffaloes, there are signs as early as 1930 that not all was well.44 In that year, the corporation of Bury St Edmund's declined an invitation to Runnymede pleading that they were themselves planning to stage their own event for the chosen date.45 There were problems over the ground to be used, with the longstanding owner of the Commemoration site, Mrs Milward, consistently unenthusiastic and, by 1933, positively hostile.46 Moreover, the foundation in 1929 of the Magna Carta Society, with Mrs Normanton in the ascendant and claiming the blessing of the late Lord Lincolnshire, left the vicar and his associates as merely the Egham branch of a much larger venture.47 Runnymede itself continued to witness dramatic events. In July 1932, just before their inauguration by the Prince of Wales, it was discovered that the commemorative pillars at the entrance to the meadow, commissioned by Lady Fairhaven to a design by Sir Edwin Lutyens, had been deliberately disfigured with creosote. In the highly -wrought language of the Evening Standard, 'quantities of evergreens were rushed by car to Runnymede and placed round the doorways and windows of the memorial houses before the Prince arrived'.48 This at a time when no less dramatic events were unfolding elsewhere in Europe, with the peaking of the National Socialist Party vote in German elections paving the way for some to suggest that an obscure demagogue, Adolf Hitler, be accommodated as a future chancellor of the Reich. In this year, for the first time since 1923, the Committee failed to secure a speaker and the Commemoration was abandoned for lack of interest. There was a brief resurgence in the following year, when Leo Amery MP was persuaded to speak. His address, reported in the Times, was a stirring summons to the defence of liberty:

'It was no theoretical freedom that the barons at Runnymede claimed for themselves and for a whole nation, but the practical freedom which came from the enforcement of the law on all without regard to privilege or power. Liberty was, indeed, a meaningless thing, except as a right adjustment between all the varying forces and elements in the national life'.

According to Amery, India now chafed under the demand for liberties to which she considered herself qualified. She should be granted her wishes, but only in such a way as to preserve liberty. In Russia and Germany the boundaries of freedom were contracting. There:

'The abandonment of liberty was being justified on every hand, not as a disagreeable necessity, but as the true ideal. There was a fanaticism of collective tyranny which was spreading widely and found its advocates even in our own midst. We could not afford to ignore the danger to British freedom from within or from without. Against the former our answer must be to bring freedom up to date, to overhaul our political machinery so as to increase its efficiency as well as its stability, to reform our economic life so that it might afford better opportunity, greater security, and more social justice to all'49

In the circumstances of 1933, this was stirring stuff. It was also the last such rhetoric launched under the auspices of the Commemoration. By this time, the Commemoration Committee was sparsely attended and often not quorate. The vicar's suggestion that, in 1934, the American Ambassador be invited to deliver an address 'though not cheered was not refused'.50 On that chill note, the committee minutes end. In 1934, as noted in the great 800th anniversary British Library exhibition, a pageant was staged at Runnymede intended to re-enact the days of 1215 in tin armour and home-stitched tabards.51 Runnymede had become a place of make-believe rather than of political excitement. It is thus that it played host to the great jamboree of 2015.

1 | Steven Franklin, with whose help this feature was prepared, is a postgraduate student at Royal Holloway, University of London. His PhD thesis explores the appropriation and commemoration of Magna Carta. |

2 | Ben Cowell, Runnymede and Magna Carta (National Trust, 2015). |

3 | For both Park Close ('Engleside') and the Park Lane House, see the rather gushing memoirs preserved at <ttp://millicentlibrary.org/cara-leland-rogers-broughton/>. |

4 | Tariff for a knighthood £10,000, a baronetcy £30,000, and a peerage between £50,000 and £100,000, marketed by both Lloyd-George and Andrew Bonar-Law: Andrew Cook, Cash for Honours: The Story of Maundy Gregory (Stroud, 2008), 141, 278, with further information from John Charmley, who tells me that he is prepared to supply similar favours for only a fraction of the Maundy Gregory price. |

5 | James Lees-Milne, Ancestral Voices (London, 1975), 237-9 (10 September 1943), and cf. idem, Caves of Ice (London, 1983), 12 (26 January 1946), 216 (23 September 1947). |

6 | Woking, Surrey Archives Ac1498/10, henceforth 'Minutes', cited by date of entries. |

7 | Chelmsford, Essex Record Office D/P 95/1/19, a reference that I owe entirely to the sleuthing of Katharine Schofield. |

8 | See the printed circular, dated at Church House, Westminster, 11 May 1915, surviving as Shrewsbury, Shropshire Record Office XP201/U/1/9. |

9 | London, University College, Royal Historical Society Archives, Minute Book 1905-14, entries for 15 January 1914 (preliminary establishment of an anniversary committee), 19 February 1914 (agreement to Lord Bryce as chairman of a 'large' committee), 19 March 1914 (circulation of the membership), although the published accounts to 31 October show that only £1 18s. 6d. had thus far been spent by the committee. Minute Book 1915-24, entries for 18 March 1915 (decision to gather up papers by midsummer, for reading where possible, with a published volume to follow), 22 October and 18 November 1915 (arrangement of a date for McKechnie's lecture), Printed Reports for 1915-16 (record of lectures delivered), 18 January 1917 (request for costings for a published volume of essays), 15 March 1917 (costing of 21 sheets at £4 7s. 9d. per sheet), 21 June 1917 (agreement to 250 additional copies beyond the 750 distributed to fellows, to be sold at a guinea each), 8 November 1917 (congratulations to the editor following publication). I am indebted to Sue Carr for access to the (disappointingly thin) archives of the Society. The published volume, Magna Carta Commemoration Essays, ed. H.E. Malden (Royal Historical Society, 1917), pp.vii-ix, xix-xx, includes an account of circumstances, and a full list of General Committee established in 1914. Felix Liebermann, whose name appears on the committee list, was presumably the 'German professor, well known for his mastery of early English law' who, according to Malden (p.xxi) sent a 'courteous letter through Sweden - suum suique tribuito - regrett(ing) his inability to contribute'. A year later, it was Liebermann's reference in the final volume of his Gesetze (1916) to the ‘justified determination’ of German aims in a World War brought about by the ‘heedless claims’ of Britain’s maritime Empire, that damned him in the eyes of English contemporaries and signalled the decline of contacts between English and German medievalists. Cf. Patrick Wormald, The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, vol.1 ('Legislation and its Limits') (Oxford, 1999), 20n. |

10 | See here the brief summary by Don MacRaild, 'The International Magna Charta Association', at <http://digitalcommunity.englishdiaspora.co.uk/?p=324>. |

11 | For background here, stressing the desire to heal the scars caused to Anglo-American relations by the American Civil War, see Peter Clarke, Mr Churchill's Profession: Statesman, Orator, Writer (London, 2012), 81-115. |

12 | Thomas Otte, ‘“The Shrine at Sulgrave”: The Preservation of the Washington Ancestral Home as an “English Mount Vernon” and Transatlantic Relations’, in Towards World Heritage: International Origins of the Preservation Movement, 1870–1930, ed. M. Hall (Farnham 2011), 109–35. |

13 | Clarke, Mr Chuchill's Profession, pp.xv, 106, 110-11 |

14 | There is a brief life by Joanne Workman, 'Helena Florence Normanton', ODNB. |

15 | In adddition to the Minutes (running from 1925), the Egham Museum possesses a printed service book for the 1924 Commemoration, including a photograph of the 1923 Commemoration, said to have been the first held at Runnymede. |

16 | For references to this pageant, see Minutes 10.xi.25, 8.vi.26 |

17 | Minutes 19.vi.25. |

18 | Report in the Times (18.xii.29) filed after Minutes for 18.vi.29. |

19 | Minutes 15.vii.27. |

20 | Minutes 12.vi.25. |

21 | Minutes 24.iv.31, 19.v.31, 15.vi.31. Marjoribanks died shortly afterwards, with the committee sending its condolences to his uncle, Lord Hailsham: Minutes 19.iv.32. |

22 | Minutes 12.vi.25. |

23 | Minutes 30.vi.25. |

24 | Minutes 11.v.26, 25.v.26, 8.vi.26. |

25 | Minutes 10.vi.26: 'Mr Hamilton: The position regarding this gentleman was again considered, and the various objections to his moving a vote of thanks were pointed out to the President, who suggested that a letter should be sent to Lord Kintore to say that the former practice of refraining from passing a vote of thanks would be strictly adhered to, but that a letter of thanks would be sent subsequently, and further pointing out that last year we had an American Bishop while next year we hoped to have the American Ambassador, and on this occasion, although several prominent Americans had been invited at the request of the E.S.U., it had been decided not to ask any of our overseas visitors to address the gathering'. |

26 | Minutes 16.xii.27 |

27 | Minutes 3.v.29. For the Magna Carta commemorations held at Bury St Edmunds, see the work of the AHRC’s Redress of the Past: Historical Pageants in Britain, 1905-2016. |

28 | Minutes 12.vi.30. |

29 | Minutes 12.vi.25. |

30 | Minutes 5.vi.28, 18.vi.28, 4.vi.29. |

31 | Minutes 19.iv.32. |

32 | Minutes 23.vi.27. |

33 | Minutes 28.vi.26. |

34 | Minutes 5.iii.26. |

35 | Minutes 11.v.26. |

36 | Minutes 25.v.26. |

37 | Minutes 10.vi.26 |

38 | Minutes 14.vi.26. |

39 | Minutes 2.iii.27. |

40 | Minutes 16.xii.27. |

41 | Minutes 7.v.28 and 3.v.29. |

42 | The Times, 18.xii.29, of which a cutting follows Minutes 18.vi.29. The deed of sale, from the Crown Commissioners to R.W.E.L. Poole and A.C. Tranter, 14 December 1929, refers only to 115 acres, 1 rod and 34 perches of land in Longmead and Runnymede, the missing 70 acres being covered, presumably, by other instruments. |

43 | Press cuttings facing Minutes 13.v.30. |

44 | Minutes 13.v.30. |

45 | Minutes 2.vi.30. |

46 | Minutes 24.iv.31 and 26.vi.33. |

47 | Minutes 3.v.29, 12.vi.30 (cutting from the Sunday Times 29.vi.30), 14.i.32, 19.iv.32, 26.vi.33. |

48 | Evening Standard 3.vii.32, preserved with Minutes 19.v.32. |

49 | Times 3.vii.33, preserved with Minutes 26.vi.33. |

50 | Minutes 26.vi.33. |

51 | See the relevant entries in the catalogue: Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy, ed. Claire Breay and Julian Harrison (London, 2015). |

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265