Leopards, Lions and Dragons: King John's Banners and Battle Flags

April 2015,

No-one who attended the recent festivities to mark the opening of the British Library's Magna Carta Exhibition can have failed to notice the extent to which heraldry and heraldic shields contributed to the visual splendour of the occasion. We know a fair amount about the heraldry of the barons of 1215, many of whom either displayed their arms on their surviving seals, or lived long enough to be commemorated by the chronicler Matthew Paris, himself an avid collector of heraldic lore and the first reliable illustrator of English coats of arms.1 By the time that King John met with the barons at Runnymede, banners and other heraldic devices were widely used to proclaim baronial allegiance.2 But what, meanwhile, of the banners and heraldry of the King?

Shortly before entering Oxford, on 6 April 1215, the King sent a command from Woodstock, translated below, for the manufacture of five tunics of arms and five banners (banerias). These were to be sent to him without delay by Reginald of Cornhill and William 'the Cook', the chief suppliers of the royal wardrobe, based in the city of London. The reference to these banners and tunics being made of beaten gold may be associated with a purchase, listed three days later, by which Richard fitz Ilger and Gilbert the Scot are recorded as having spent 27 marks (£18) at Woodstock on 3 marks weight (2 lbs) of gold: a conversion rate in line with contemporary expectations, of roughly £9 of silver for 1lb weight of gold.3 Extrapolating here, and allowing for an artificial estimate of ten tunics and banners each using an equal quantity of gold, we would be dealing with items each supplied with more than 3 ounces of gold. In other words, what was commanded would have offered a truly magnificent display of the King's arms.

The arms of King John are most famously and prominently displayed on the equestrian side to the King's seal, there shown as three lions passant gardant, facing to the left. Elsewhere, there have been several previous efforts, most notably by Adrian Ailes, to trace the development of this shield of arms from the symbol of the lion, first certainly recorded for John's great-grandfather, King Henry I, thereafter adopted by Geoffrey count of Anjou, King John's grandfather, and by Geoffrey's Plantagenet successors.4 Geoffrey's younger son, King John's uncle, William (d.1164), was the first member of his family certainly recorded as having incorporated a lion (rampant) within the imagery of his seal.5 Lions were thereafter closely associated with, although not used on the seal of King Henry II.6 Richard I followed this trend, incorporating a single lion rampant facing to the right onto the shield of his first great seal, employed from 1189 onwards. With the introduction of Richard's second seal, perhaps manufactured as early as 1194-5 although not put into use until 1198, this was transformed into what henceforth became the standard representation of three lions couchant or passant, now facing right to left rather than left to right.7 On this, Richard's second great seal, a lion passant was also represented on the helmet of the equestrian side, today largely invisible, but reported by various antiquaries as perhaps the first evidence in western heraldry for the use of crests.8 Lions are also recorded (two lions passant/couchant facing to the left) on the shield of the single-sided equestrian seal that King John employed before his accession as King. This is today known only from impressions attached to charters issued as count of Mortain, after 1189, but bears an inscription identifying John as son of Henry II and lord of Ireland, without reference to Mortain, hence almost certainly first used before 1189, perhaps made at the time of John’s knighting in 1185.9 Although by the 1230s identified as leopards rather than as lions, there is no doubt that these three beasts began as lions, thereafter metamorphosing into something half way between lion and leopard.10

So much for the King's arms. It was presumably these same three lions passant gardant, facing right to left, coloured in gold (roughly one ounce of gold per lion) that appeared on the tunics and perhaps on the banners commissioned in 1215. Uncertainty here is generated by the fact that on subsequent occasions when kings of England are known to have ridden behind five banners, under Edward I at the siege of Caerlaverock in 1300, and under Henry V at Agincourt, for example, only some of these banners (two at Caerlaverock, only one at Agincourt) displayed the lions or leopards of England. The others were devoted to the symbols of particular saints (Edmund at Caevarlock, Edward the Confessor and St George at both Caerlaverock and Agincourt), of the Virgin Mary, and of the Holy Trinity (Agincourt).11 The background to the golden lions would have been red ('or on gules'). Matthew Paris supplies illustrations to this effect.12 Most remarkably in the decorated capital initial 'E' to letters patent of Edward I issued to the men of Agen in Gascony in 1286 we have a magnificent representation of the King seated in majesty, with crown, orb and sceptre, in front of a great cloth of state decorated with at least fifteen lions passant gardant, or on gules, facing right to left.13 Besides his banners decorated in this way, the 'tunics for arming' ('tunicas ad armandum') that John commissioned in March 1215 imply livery for servants of the court. Indeed, they supply further proof for the existence of court officers who in due course were to become known as 'kings of arms', already, as David Crouch has shown, active at the court of Henry II, as early as the 1180s.14

Such tunics and banners in fact first appear in the chancery and Exchequer records of John's reign, several years before 1215. In April 1208, the Exchequer was ordered to account Reginald of Cornhill 49s. 10d. 'for preparing our banners and tunics for arming', 20s. for fixing ('cubare') the gold in place on banners and tunics, 3s. for creating images ('depingere') for the same, and 8s. 'for sewing'.15 These orders, like those of 1215, may suggest banners made either of rigid metal or with beaten gold decoration, rather than cloth flags sewn with gold thread. The sewing of 1208 could have been for the tunics alone. At Michaelmas 1212, we find John fitz Hugh reclaiming the cost of 'a doublet ('purpuctus') and three tunics of arms for the King's work, and twelve pennants and four plate banners for the same', the reference here to 'plate banners' ('baneris platis') once again suggesting banners made of hammered metal rather than of cloth.16 To this extent, modern writers should beware of the tendency to imagine medieval armies 'unfurling' their banners. On the contrary, the banners described here were perhaps more likely to 'clang' than to 'flutter'.

The distinction between pennants and banners occurs again in a source written very close to 1212, in the London collection of laws in which the men of each London parish, when mustered for defence, were expected to have a pennant, these parish pennants being carried behind the banner of each respective city alderman.17 Elsewhere, between 1198 and 1219, we have several references to Robert fitz Alan of Nether Worton in Oxfordshire holding a serjeanty of 40s. in return for the service of 'carrying the banner of the foot levies of the hundred of Wootton' at his own expense, receiving 2d. a day from the King should he have to carry his banner outside the county or in going to the sea.18

It is worth noting that the commissioning of banners for the King, both in 1208 and 1215, was undertaken in April, around Easter-time. In 1208, the King was not engaged in military preparations, suggesting that on both occasions banners and tunics were ordered for triumphal display, perhaps for the solemnities of Easter, rather than for specific military use. Here we can perhaps draw an important distinction between the King's heraldic banners (assumed to have shown the lions or leopards of England), and the war standard carried by kings of England into battle.

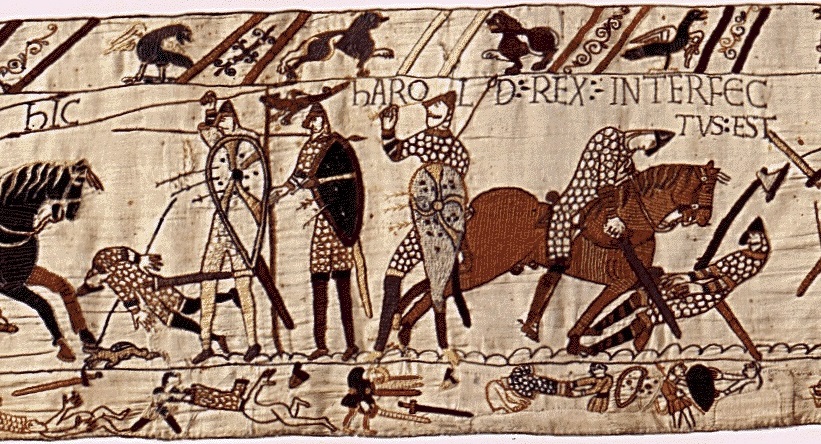

So far as we can judge, the battle standard of King John, like that of his ancestors, took the form of a dragon rather than of three gold lions. The dragon standard of the kings of Wessex is at least twice referred to by Henry of Huntingdon, writing of events long before 1066, and can almost certainly be identified with the dragon that the Bayeux Tapestry shows at Harold's side during the battle of Hastings.19 William of Normandy, by contrast, is shown in the Tapestry as fighting at Hastings under an entirely different sort of flag, identified by twelfth-century writers, though not apparently before this, as the 'papal banner' granted to him by Pope Alexander II.20

The symbol of the dragon was nonetheless already deeply woven into the symbolism both of battle elsewhere in northern Europe and of ducal Normandy, not least through the association of a dragon with the cult of Saint Romanus, patron-saint of Rouen – the ducal capital.21 This 'Draco Normannicus' is commemorated in Etienne of Bec's epic poem of the 1160s, and almost certainly explains the widespread use of serpentine or dragon imagery at the court of King Henry II, not least in the naming of the King's ship as the 'snake' or 'esneccum'.22 It reappears in the 1190s as the dragon standard ('vexillum terribile draconis') that Richard I is said to have had carried before him both in Sicily and later, fighting Saladin at Arsuf in the Holy Land.23 Banners, indeed, played a significant role in Richard's crusade. Besides the flag ('vexillum') of the Duke of Austria, which Richard is reported to have hurled from the battlements of Acre, we are told of the banners ('baneria') that Richard flew over the captured city of Messina, which the French king ordered be flown lower than his own standard ('vexillum'), as well as of a golden imperial standard ('vexillum imperiale per totam auro desuper contextum'), captured by Richard on Cyprus, subsequently dispatched to England as a gift to the monks of Bury St Edmunds.24

Battle flags undoubtedly featured in the civil war of 1215-16.25 It was under the sign of the dragon, the most ferocious of beasts, that King John himself fought this war. In all likelihood, the dragon by this time carried a legal as well as a symbolic significance, implying war to the death and without quarter.26 Ralph of Coggeshall informs us that, in the Spring of 1216, Louis of France attempted to take John by surprise at Winchester, 'hearing that the King had raised the dragon battle standard ('insigne bellicum draconem') .... But John, learning of his arrival, lowered his dragon ('draco') and fled, having first burned four parts of the city'.27 Henry III commanded just such a dragon banner in 1244. Made of red samite stencilled with gold, it had a tongue of burning fire depicted as if in constant movement, and eyes of sapphire or other precious stones. The intention was that it be deposited at Westminster Abbey, apparently as an English counterpart to the Oriflamme of France, long held at Saint-Denis.28 A century later, King John's great-great-grandson, Edward III, fought at Crécy (1346) under a dragon standard, apparently with the intention that the leopards/lions of England and the French fleur-de-lys here deliberately yield place to the 'cruelty of the dragon'.29 Meanwhile, although there is good reason to suppose that the Oxford meeting of early April 1215 marked a crucial turning point in relations between King John and his barons, it would be wrong to suppose that the King's commission for armorial tunics and banners revealed any intention on his part to make war on his rebellious subjects. Rather, what we have here is evidence of the extent to which, even as early as April 1215, heraldry and display were crucial to the advertisement of royal, as of baronial power. How much more magnificent, we may well wonder, were these advertisements to become by the time that King and barons met at Runnymede two months later.

Letters of King John commissioning the making of five tunics and five banners. Woodstock, 6 April 1215

B = TNA C 54/9 (Close Roll 16 John) m.6. C = TNA C 54/10 (Duplicate of B) m.6.

Pd (from B) RLC, i, 193b.

Rex Regin(aldo) de Cornhull' et Willelmo Coco etc. Mandamus vob(is) quod sub festinacione fieri faciatis ad opus nostrum quinque tunicas ad armand(um) et quinque banerias de armis nostris bene auro bacuatas, et custum quod ad hoc posueritis per visum et testimonium leg(alium) hominum computatur vob(is) ad scaccarium. T(este) me ipso apud Wodestok', vi. die April(is) anno r(egni) n(ostri) xovio.

The King to Reginald of Cornhill and William the Cook etc. We order you speedily to have made for us five tunics for arming and five banners well made with beaten metal with our arms in gold, and the cost that you incur here by view and testimony of law-worthy men will be accounted to you at the Exchequer. Witnessed myself at Woodstock, 6 April in the 16th year of our reign.

1 | For Paris' coats of arms, generally used as illustrations for his obit notices of particular individuals, see 'The Matthew Paris Shields c.1244-59', ed. T.D. Tremlett, in Rolls of Arms Henry III, ed. T.D. Tremlett, H.S. London and A. Wagner, Aspilogia ii (London, 1967), 1-86, and Suzanne Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris in the "Chronica Majora" (Berkeley, 1987), esp. pp.41-3, 174-6, 198-201. |

2 | Amongst the vast literature on the emergence of the science of heraldry in twelth- and thirteenth-century England, see in particular Adrian Ailes, 'Heraldry in Twelfth-Century England: The Evidence', England in the Twelfth Century, ed. D. Williams (Woodbridge, 1990), 1-16; idem, 'Heraldry in Medieval England: Symbols of Politics and Propaganda', Heraldry, Pageantry and Social Display in Medieval England, ed. P. Coss and M. Keen (Woodbridge, 2002), 83-104; idem, 'The Knight's Alter Ego: From Equestrian to Armorial Seal', Good Impressions: Image and Authority in Medieval Seals, ed. N. Adams, J. Cherry and J. Robinson, British Museum Research Publications clxviii (London, 2008), 8-9; John Cherry, 'Heraldry as Decoration in the Thirteenth Century', England in the Thirteenth Century, ed. W.M. Ormrod (Stamford, 1991), 123-3. |

3 | RLC, i, 193b, and for contemporary estimates of a conversion rate of roughly 10 to 1 for gold to silver, see D. A. Carpenter, 'The Gold Treasure of King Henry III', Thirteenth Century England I, ed. P. Coss and S.D. Lloyd (Woodbridge, 1986), 63-4, 87n.; N. Vincent, Peter des Roches: An Alien in English Politics, 1205-1238 (Cambridge, 1996), 238-9. |

4 | A. Ailes, The Origins of the Royal Arms of England: Their Development to 1199 (Reading, 1982), and more recently, N. Vincent, 'The Seals of King Henry II and his Court', and A. Ailes, 'Government Seals of Richard I', in Seals and their Context in the Middle Ages, ed. P.R. Schofield (Oxford, 2015), 7-33, 101-110. For the Plantagenet adoption of the symbol of the lion, see now Vincent, 'Seals of Henry II', 16-19. |

5 | Vincent, 'Seals of Henry II', 13 fig. 2.6, 18. |

6 | Ibid., 17-19. |

7 | Ailes, 'Seals of Richard I', 101-4. |

8 | Ailes, 'Seals of Richard I', 102, and cf. A. Deville, 'Dissertation sur les sceaux de Richard-Coeur-de-Lion', Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de Normandie (1830), 61-89, at p.79-80 reporting the crest from an impression of the seal, now Rouen AD 13HP8 (The Itinerary of King Richard I, ed. L. Landon, PRS new series xiii (1935), no.494), itself reproduced as an engraving in A. Deville, Essai historique et descriptif sur l'église et l'abbeye de Saint-Georges-de-Bocherville (Rouen, 1827), pl.VI facing p.77, also seen and described by John Doubleday, in Archaeologia, xxvi (1836), 461, from an impression attached to TNA DL 10/47 (Landon, Itinerary, no.500), now somewhat rubbed (Ailes, 'Seals of Richard I', 102 fig. 7.3b). The crest is also shown by Landon, Itinerary, opposite p.172, from an original, now Canterbury Cathedral Archives ms. Chartae Antiquae B349. Doubleday (and before him, Francis Sandford) identified the scrolling around the top of the helmet as a representation of broom cods or plante-de-genêt. Deville ('Dissertation', p.80) attempts to identify it as baleen or whalebone, citing Guillaume le Breton to the effect that baleen was employed in the decoration of helmets, and cf. Guillaume le Breton, 'Philippidos' IX.519-20, in Oeuvres de Rigord et de Guillaume le Breton historiens de Philippe-Auguste, ed. H.-F. Delaborde, 2 vols (Paris, 1882-5), ii, 270. In reality, Guillaume's reference is almost certainly intended as a pun linking the crest's substance and its wearer, Renaud count of Boulogne/baleen. |

9 | Adrian Ailes, ‘The Seal of John, Lord of Ireland and Count of Mortain’, The Coat of Arms, n.s. iv (1981), 341-50, and for particular examples, see Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals, ed. L.C. Loyd and D.M. Stenton (Oxford, 1950), 57 no.82; Earldom of Gloucester Charters, ed. R.B. Patterson (Oxford 1973), 24 and pl.xxxii a-b, and the description from an original now at Durham, available online as no.3023 [at http://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ead/dcd/dcdmseal.xml#ERs], noting the inscription +SIGILLVM IOHANNIS FILII REGIS DOMINI HIB'NIE, from Durham, University Library Archives and Special Collections ms. D. & C. Durham 2.4.Ebor.20. |

10 | Vincent, 'Seals of Henry II', 18. |

11 | As cited, without references, by J.H. Round, The King’s Serjeants and Officers of State with their Coronation Services (London, 1911), 388. |

12 | 'The Matthew Paris Shields', ed. Tremlett, 11-17, 36, 57-60. |

13 | From Agen, Archives départementales de Lot-et-Garonne, Archives de la ville d'Agen AA3, as recently drawn to my attention by Elizabeth Danbury, and in turn first noticed by our mutual friend, Ghislain Brunel. Printed, without notice of the decoration, Archives Municipales d'Agen: Chartes première série (1189-1328), ed. A. Magen and G. Tholin (Villeneuve-sur-Lot, 1876), 123-4 no.75. Compare the wool, silk and linen seal bags embroidered with a lion or three lions used to protect seals of Edward I on a variety of charters including those noticed by F. Pritchard, 'Two Royal Seal Bags from Westminster Abbey', Textile History, xx (1989), 225-34; Vincent, 'Seals of Henry II', 30 n.115. |

14 | David Crouch, ‘The Court of Henry II of England in the 1180s, and the Office of King of Arms,’ The Coat of Arms, 3rd ser. v (2010). |

15 | RLC, i, 109, a command issued at Guildford on 7 April, the day after Easter, 'pro auro ad banerias nostras et tunicas nostras ad armandum parandas et viginti s(olidos) pro auro illo cubando in baneriis et tunicis et tres s(olidos) pro baneriis et tunicis illis depingendis et octo s(olidos) pro quadraginta s. suend(is)'. The last detail here remains obscure, perhaps suggesting the sewing of particular motifs (?forty stars, 's(telle)'), perhaps the employment of forty individuals in the sewing of these things. Cf. Pipe Roll 10 John, 97, where the item reappears in Reginald of Cornhill's account rendered at Michaelmas 1208, as £4 10d. 'pro auro ad banerias et tunicas r(egis) ad armandum et pro illis faciendis'. For this and various subsequent references, I am indebted to the assembly of references in the Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources, Fascicule I 'A-B' (Oxford,1975), 179 col.3 sub 'banera/baneria/banerium'. |

16 | Pipe Roll 14 John, 44: 'pro .... i. purpucto ad opus r(egis) et iii. tunicis armatoriis ad opus r(egis) et xii. penuncellis et iiii. baneris platis ad opus eiusdem'. |

17 | M. Bateson, 'A London Municipal Collection of the Reign of John', English Historical Review, xvii (1902), 728: 'Item in qualibet parrochia fiat unum penuncellum, et aldermannus suam habeat baneriam, et homines de singulis parochiis, cum penuncellis suis, sequantur baneriam aldermanni sui, cum sumonicionem aldermanni sui habu(er)ri(n)t, loco istis statuto ad ciuitatem defendendam'. |

18 | Book of Fees, i, 11 ('per seruicium portandi baneram populi prosequentis per marinam'), 104 ('per seruicium ferendi banarium domini regis pedes infra iiii. portus Anglie, et inde debet habere ii. d(enarios) per diem'), 253 ('per serganteriam portandi baneriam omnium peditum hundredi de Wotton' ad custum suum in ipso comitatu, et ipse Robertus extra comitatum debet habere de bursa domini regis ii. d. faciendo seruicium predictum qualibet die'), and cf. VCH Oxfordshire, xi, 286-7. |

19 | N.P. Brooks and H.E. Walker, 'The Authority and Interpretation of the Bayeux Tapestry', Anglo-Norman Studies, i (1979), 32-3, citing Henry of Huntingdon IV.19 and VI.13, for which see now Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, The History of the English People, ed. D. Greenway (Oxford, 1996), 242 ('regis insigne, draconem scilicet aureum'), 358 ('inter draconem et insigne quod vocatur Standard'). |

20 | I. S. Robinson, The Papacy 1073-1198 (Cambridge, 1990), 307-8, citing William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum Anglorum, III.243 (ed. R.A.B. Mynors, R.M. Thomson and M. Winterbottom, 2 vols (Oxford, 1998-9), i, 454), which actually refers to a standard decorated with the figure of a warrior, sent after the battle by William to the Pope ('vexillum illud post victoriam papae misit Willelmus, quod erat in hominis pugnantis figura, auro et lapidibus arte sumptuosa intextum'). The full story of the papal standard carried into battle by William first appears in the writings of Wace ('Roman de Rou', lines 7575-7614), themselves almost certainly informed by close acquaintance with the Tapestry at Wace's own cathedral of Bayeux: The History of the Norman People. Wace's Roman de Rou, ed. and trans. G.S. Burgess (Woodbridge, 2004), 176, at p.179 (lines 7811-82) claiming that it was the standard of Harold that William later captured and sent in tribute to the Pope. |

21 | Brooks and Walker, 'Authority and Interpretation', 32, citing the dragon standards attributed to the Saxons by Widukind of Corvey, and by the tenth-century 'golden psalter' of St Gallen to Joab setting out to make war on the Syrians and the Ammonites, citing the illustration in A. Merton, Die Buchmalerei in Sankt Gallen (Leipzig, 1923), plate xxix.i. |

22 | Vincent, 'Seals of Henry II', 15-16. |

23 | The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes of the Time of King Richard the First, ed. J. T. Appleby (London, 1963), 23 ('Rex Anglie procedit armatus, vexillum terribile draconis prefertur expansum, clangor tube post regem mouet exercitum'); Chronica magistri Rogeri de Houedene, ed. W. Stubbs (4 vols. London, 1868-71), iii, 129 ('Et rex Anglie fixisset signum suum in medio, et tradidisset draconem suum Petro de Pratellis ad portandum, contra calumniam Roberti Trussebut, qui illum portare calumniatus fuit de iure predecessorum suorum'). |

24 | Richard of Devizes, ed. Appleby, 46-7; Itinerarium peregrinorum et gesta regis Ricardi, ed. W. Stubbs (London, 1864), 164-5 (ii.17); Howden, Chronica, ed. Stubbs, iii, 107-8. |

25 | See, for example, the knight reported as carrying the banner of the avoué of Béthune at the siege of Dover in 1216, referred to in Histoire des ducs de Normandie et des rois d’Angleterre, ed. F. Michel (Paris, 1840), 178. |

26 | Matthew Strickland, 'A Law of Arms or a Law of Treason? Conduct in War in Edward I's Campaign in Scotland, 1296-1307', Violence in Medieval Society, ed. R.W. Kaeuper (Woodbridge, 2000), 56-7. |

27 | Radulphi de Coggeshall Chronicon Anglicanum, ed. J. Stevenson (London, 1875), 182: (Louis) 'Deinde, captis quibusdam castellis, properauit occupare regem Iohannem, quem audierat apud Wintoniam insigne bellicum draconem erexisse, quasi Lodouicum bello excepturus, si adueniret. Sed Iohannes, cognito eius aduentu, draconem suum deposuit et aufugit, inflammata prius urbe per quatuor partes'. |

28 | Close Rolls 1242-7, 201: 'Fieri etiam faciat unum draconem in modo unius vexilii de quodam rubeo samitto, qui ubique sit auro extencellatus, cuius lingua sit facta tanquam ignis comburens et continue apparenter moueatur, et eius oculi fiant de saphiris vel de aliis lapidibus eidem conuenientibus, et illum ponat in ecclesia beati Petri Westmonasteriensi contra aduentum regis ibidem' (17 June 1244). |

29 | Chronicon de Galfridi Baker de Swynebroke, ed. E.M. Thompson (Oxford, 1889), 83: 'Ita vexillum ad dextram stacionardi regalis Francie habuit aurea lilia lata cum filis aureis a lateribus vexilli regii Francorum, quasi in vacuo dependencia. E contra rex Anglie iussit explicari suum vexillum, in quo draco armis suis togatus depingebatur et abinde fuit nuncupatum 'Drago', significans feritatem leoparditam atque miticiam liliorum in draconcinam crudelitatem fuisse conuersam'. |

Referenced in

The rebels seize London (The Itinerary of King John)

Court held at Oxford (The Itinerary of King John)

- January 2016

Exchange of Letters between King and Rebels - December 2015

Partridges and a Pear Tree - December 2015

The Saving Clause in Magna Carta - December 2015

Christ's College and Magna Carta - November 2015

The Arms of Roger Bigod - October 2015

Ten Letters on Anglo-Papal Diplomacy - September 2015

The Leges Edwardi Confessoris - July 2015

New Letter of the Twenty-Five - July 2015

Runnymede and the Commemoration of Magna Carta - June 2015

Who Did (and Did Not) Write Magna Carta - June 2015

Date of Magna Carta - June 2015

A Lost Engrossment of 1215? - May 2015

A Glimpse of Rebel London - May 2015

The Rebel Seizure of London - May 2015

Papal Letters of 19 March - May 2015

The Copies at Lincoln and Salisbury of the 1215 Magna Carta - May 2015

The copies of Magna Carta 1216 - May 2015

The Magna Carta of Cheshire - April 2015

Dating the Outbreak of Civil War - April 2015

More from the Painter Archive - April 2015

A Magna Carta Relic in Pennsylvania - April 2015

A Lost Short Story by Sidney Painter - April 2015

King John's Banners and Battle Flags - March 2015

King John’s Lost Language of Cranes - March 2015

Magna Carta and Richard II's Reign - March 2015

The King Takes the Cross - February 2015

Irish Fines and Obligations - January 2015

John negotiates with Langton over Rochester - January 2015

Conference at New Temple - December 2014

Simon de Montfort's Changes to Magna Carta - November 2014

Meeting at Bury St Edmunds - October 2014

King John Forgets his Password - September 2014

Treaty 18 September 1214 - September 2014

Letter of King John 9 July 1214 - September 2014

Letter of Aimery Vicomte of Thouars - August 2014

The Freedom of Election Charter - July 2014

The Witness Lists to Magna Carta - April 2014

The Cerne Abbey Magna Carta - March 2014

Confirmation of Magna Carta in 1265