Rising Panic at John's Easter Court

by Professor Nicholas Vincent

19 April 1215 - 25 April 1215

| Date | Place | Sources | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

19-22 Apr 1215 |

RC, 206b; RLP, 133b-134; RLC, i, 195b-6b, 198-8b, 203 |

||

22 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 133b |

||

23 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 134 |

||

23 Apr 1215 |

RLC, i, 196b, 198 |

||

23, 25 Apr 1215 |

RLP, 134; RLC, i, 196b |

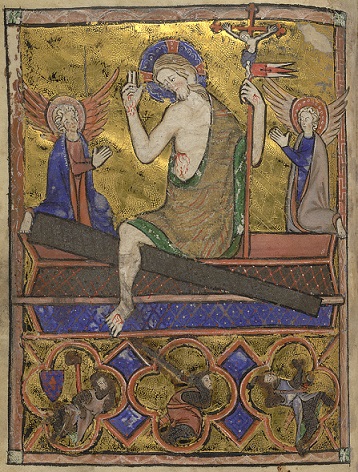

The present week began with the festivities of Easter Sunday. Preparation for these had been under way for several days, with the dispatch to London of serjeants to make ready for the King's feast.1 As in previous years, the 'Laudes' were sung, the great celebration of Christian kingship opening 'Christus vincit, Christus regnat, Christus imperat', performed before John on Easter Sunday this year by Master Henry of Cerne and Robert of Saintes, clerks of the King's chapel.2 A well known anecdote, told in the Life of St Hugh of Lincoln, suggests that John himself had in the past found the solemnities of Easter tiresomely prolonged. At Easter 1200, the first such festivity of his reign, keen to break his fast, and bored with the sermon, he had sent up a message not once but three times to demand that the bishop cease preaching so that the King might dine.3 We do not know who preached the Easter sermon in 1215. However, it is likely that the preacher, whoever he may have been (and the bishop of London was perhaps the most plausible candidate), took the opportunity to refer to John's crusading vows. John himself, after all, was established in the Temple precinct, and his taking of the Cross, in March, remained easily the most significant demonstration of his new-found loyalty to the Church.

On Wednesday 22 April, three days after Easter, the King wrote to a man named John son of Leonard de Venicia (presumably 'of Venice') asking that he come to England without delay, before the end of June.4 He is presumably the same as the John de Venuz to speed whose coming to England the abbot of Stratford Langthorne (Hammes) was promised £10 from the farm of (West) Ham in Essex.5 Venice had played a notorious role in supplying the Fourth Crusade with the fleet that, in 1204, sacked Constantinople. Somewhat closer to home, the King's crusading plans may also have informed his negotiations with the men of Bayonne. It was Bayonne that, in 1190, had supplied the fleet for Richard I's crusade.6 For many years thereafter, Bayonne had been crucial to the defence of southern Gascony, not least against the threats posed, since 1204, by both Castile and Navarre.7 The city's relations with England had not always been easy. In May 1210, for example, we find a payment of a mark 'to a certain messenger of Bayonne whom the King struck'.8 The city's governance, by twelve 'jurati' and a 'consilium' led inevitably to calls for a mayor, following in the tradition of Rouen and subsequently of London.9 No such official is mentioned in royal letters, issued on Easter Sunday, 19 April 1215, commanding the twelve and the council of Bayonne to swear oaths of obedience to the Church, as requested by the legate in France, presumably Cardinal Robert Courson. These oaths were to be made 'saving the King's right and dominion'.10 The existence of a mayor of Bayonne was nonetheless for the first time acknowledged by the King on 18 April 1215, when the mayor, in company with the twelve 'jurats' and council, was told to respect royal letters of protection.11 The mayor was addressed again, on 22 April, when, together with the 'consulate' ('consulatus') of Bayonne, he was commanded to enforce a reallocation of land originally granted by King Richard I.12

Most notably, and in many ways the climax of these negotiations, the mayor was addressed in a charter issued on Easter Sunday, granting Bayonne the same rights to a commune as were enjoyed by the men of La Rochelle (whose commune had existed since at least July 1199).13 What precise difference these grants made to local government in Bayonne remains difficult to determine. Nonetheless, it is clearly significant that the King's acknowledgement of both mayor and commune came at this time. Royal favour to the men of Bayonne, like the slightly earlier acknowledgement of the mayoralty at Northampton, or the slightly later grant to the Londoners of an elected mayor, was a direct result of King John's political predicament.14 It may also explain the bringing together in the Tower of London on 22 April of prisoners, many of them with distinctly Spanish or Basque names, all of them said to have been taken at 'Bourg' (unidentified), now released into the custody of William Herbert perhaps with the intention of exchanging them for other captives in France.15

Bayonne's potential significance to John's crusading plans perhaps played some role in the favours its men received. At the same time, these negotiations formed part of a wider attempt to grapple with the problems of Gascony and the south. This in itself seems to have been provoked by the decision of the bishop of Limoges to repudiate any fealty to King John and to reopen hostilities against the men of the city of the Limoges. On Easter Sunday, the King wrote to the archbishop of Bordeaux, the prior of Grandmont, Hugh de Lusignan count of La Marche, and the citizens of Limoges warning them of this, a day later asking that they help restore peace.16 He subsequently requested assistance from local religious for the citizens of Limoges in their attempts to defend their city.17

The grant of a commune to Bayonne is one of two charters recorded this week. The other, preserved on the Charter Roll (indeed the first such there preserved since January), and following on from favours shown to the men of Devon in the previous week, now confirmed the men of Cornwall in complete disafforestation of their county, relinquishing all right over those limited areas that had previously been retained under forest law. In addition, John confirmed the men of the county in all liberties and free customs enjoyed in the time of Henry II, regulated disputes over the stannaries (the Cornish tin mines, feared to be drawing men away from local to royal lordship), placed the sheriff of Cornwall (here tellingly referred to as the 'vicecomes patrie') in control of all ports and escheats, and placed limits on the scutage that could be charged against the so-called 'small' fees of Mortain, henceforth to be charged at only two thirds of the rate charged against standard knights' fees elsewhere. Sheriff's aid was declared abolished. The charter was witnessed by the principal ecclesiastical authority in the far west, Simon of Apulia, bishop of Exeter.18 A few days later, the King confirmed the barons, knights and free men of Cornwall in their right to free election of their sheriff, confirming their decision that William Wise and his heirs were to hold the hundred of East Wiveshire (on the county boundary with Devon) for an annual fee farm of only half a mark.19 For all of this, the men of Cornwall seem to have offered the not insubstantial sum of 1200 marks (£800) and four palfreys.20 Disafforestation and elected sheriffs had long been sought in the western counties.21 Even so, what we have here in embryo are concessions (restrictions on royal forest, on scutage, and the exactions taken by sheriffs, a general confirmation of liberties and free customs, and a specific address to barons, knights and free men) that in due course the Articles of the Barons, and then Magna Carta, were to extend to the realm as a whole.

The Cornish charter survives as the first item on a membrane of the Charter Roll that thereafter records a selection of charters issued in May 1215.22 It should remind us that the record-keeping capacities of royal government were themselves highly fallible, as proved here by the chancery's loss of all intermediate charter business between January and late April 1215. It is perhaps mere coincidence that the same day that witnessed the resumption of record keeping on the Charter Roll also saw the beginning of new membranes on both the chancery Close and Patent Rolls, the Close Roll membrane being marked at its head with a notice that 'Here W(illiam) Cucuel received the rolls to keep'.23 William ranks as the first named keeper of public records, patriarch of a distinguished line of 'Masters of the Rolls' that continues to the present day.24 His name (more likely 'Cuckoo Well' than 'Cook Well') is perhaps a pun on his function as echoer of past business. His appointment, in April 1215, followed on from a period of chaos and only haphazard keeping of the rolls since the time of the King's return from Poitou the previous October. In this context it is worth noting that this period of neglect coincided with the retirement from the court of various prominent officials previously associated with the chancery: the chancellor, Walter de Gray, promoted bishop of Worcester, the vice-chancellor, Ralph Neville, promoted dean of Lichfield, and the royal chamberlain, William of Cornhill, promoted as bishop of Coventry.

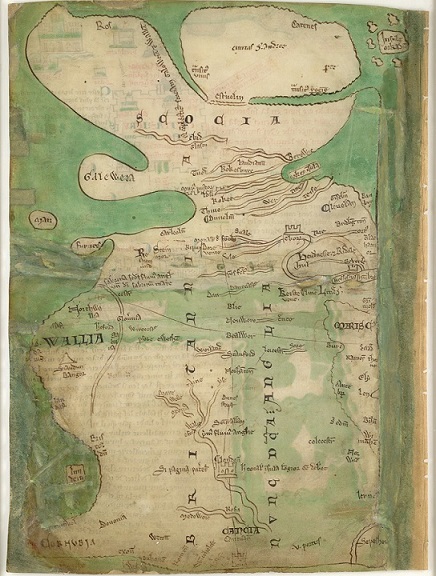

Meanwhile, the Cornish charter may also suggest, as was subsequently to become apparent, that the King's affairs in the far west were spiralling into chaos. This, indeed, may explain why John, rather than travelling north, as had been agreed in January, to meet with the barons at Northampton on the Sunday after Easter (26 April), instead travelled south and west, crossing the Thames by the bridge at Kingston, heading via Alton and Clarendon, ultimately in the direction of Corfe. His intention here may have been to put down a rumoured western rebellion. In the meantime, the chroniclers are agreed that the barons met this week, in force, armed but not yet openly hostile. Stamford, their meeting place, was a well-known site for tournaments, lying at a convenient junction for those coming from the north, from the midlands or from the Home Counties.25 The only sign this week of a continued dialogue with the rebels comes in the form of letters issued on 23 April offering safe conduct to all whom Archbishop Langton might bring to talk with the King, to last until the coming feast of the Ascension (28 May).26

The King's own military preparations continued. A group of leading officials in the north (Gilbert fitz Reinfrey, John de Lacy constable of Chester, Robert de Vieuxpont, Geoffrey de Neville, Philip of Oldcotes and Brian de Lisle) was told to obey orders in writing from Peter des Roches, passing these letters on once they had been read.27 The fact that at this stage both John de Lacy and Gilbert fitz Reinfrey, future rebels, were still addressed as trusted royal servants supplies some indication that the King's was unaware as yet of the full extent of the opposition. Gilbert fitz Reinfrey, indeed, was sent ten mounted serjeants whose wages he was expected to pay, whilst a further two dozen, many of them Flemings were sent to support Brian de Lisle.28 The castles at Hertford, Lincoln, Fotheringay, and the city of York were all put under defence, several of these orders being dispatched on Easter Sunday, a sign perhaps that panic was beginning to infect the court.29 Philip of Oldcotes was sent a Norman knight to assist him, and was instructed to extend a loan of 60 marks to Richard de Umfraville, clearly in the hope of Richard's military support.30 A man named Nicholas 'the smith' was sent to assist the constable of Devizes with mass production of crossbow bolts.31

The costs of these preparations continued to mount. Some of the King's mercenaries could be paid hand to mouth from local revenues. Wine that the King and his court had drunk at Oxford in the days leading up to Palm Sunday (totalling nearly £10) was paid for by the reeves of Oxford out of their coming year's rent.32 The costs of garrisoning Fotheringay with twenty serjeants were met by setting aside a fixed part of the local county farm.33 This in itself is significant, however, as clear evidence that the ordinary revenues of the Exchequer were now being anticipated, in order to pay for defence. In the meantime, the King's capital treasure, stored in the Tower of London, was rapidly depleted. Letters issued on 22 April commanded Peter des Roches to send £400 from the Tower to the King in the New Temple, and on the same day the King acknowledged receipt of a further £1000 from this treasure, sent to him at Reading, Windsor and the Temple in the previous week.34 Expenditure on this scale was not sustainable. It may also help to explain the King's renewed interest in seizing the property of the Jews: a Jewish house at Oxford granted to Colin (i.e. Nicholas), a brother of Fawkes de Breauté, others in Northampton granted to the Templars.35

With Flanders now vital to the recruitment of mercenaries, the men of Ypres were promised freedom of trade, provided that they repaid debts they owed the King, for the most part from subsidies that they had received in 1214 but that still remained unspent. The letters setting out these arrangements were distinctly threatening: the men of Ypres, they pronounce, will settle their debts at Paris by mid June, doing the King's will, or else the King himself with do his will by their fellow citizens then in England.36 Henry, duke of Louvain, was promised the restoration of his English rents, and in the north, Philip of Oldcotes was told to release a Flemish ship detained at Newcastle, if it was arrested after the alliance ('confederatio') reached with Ferrand count of Flanders.37 The negotiations for such an alliance had first been put in train in 1212. But the present letters suggest a further renewal of terms, perhaps after Bouvines but before April 1215, perhaps made as part of the King's French negotiations conducted from Dover in early March.38 Just as relations with Flanders were now crucial, so it was important that the King keep on terms with the papacy. On 23 April, a 5 mark annual fee was promised to Luke, clerk of Master Pandulf, the King's 'dear and special friend'.39 On the same day, the King sent a most extraordinary letter to the Pope, in defence of one of his clerks, Master Alexander of St Albans, apparently the victim of malicious attacks before the papal curia.40 The identity of this Master Alexander, perhaps a defender of royal interests during the period of Interdict, has long exercised historians.41 What has perhaps not been noticed is the dense scriptural and patristic learning packed into the King's letters. Here we find references to St Jerome's preface to Ezekiel, to other books of scripture (Numbers 12:1; Isaiah 59:17), and most remarkably, in an English tag, a description of the seven churches of Revelations 1:11 as 'sevnchurch'. Earlier in the year, we noted royal letters preserving the first recorded use in chancery of French as a language of record. Here, even more remarkably, we find one of the earliest official lapses into an English vernacular.42

The rapprochement between the King and Walter de Lacy continued in the present week with the release of yet further prisoners seized in the Lacy castle of Carrickfergus in 1210.43 Most remarkably, on 22 April, the King now wrote to Hugh de Lacy, Walter's brother. Since 1210, Hugh had been forced into exile and deprived of his earldom of Ulster. He was now reminded that the terms of a much earlier fine made by Walter for the recovery of Ulster had not been kept, and that neither Walter nor Hugh had made any attempt to secure payment to the King. The King had therefore had no choice 'but to deal with the aforesaid land of Ulster as if with our own land, doing there what suits us'.44 In all respects, these were disingenuous claims. What is remarkable is that the King felt compelled to make them. As the French might put it: 'qui s'excuse s'accuse'. By defending his actions, John revealed all the more clearly that he now had his back against the wall.

1 | RLC, i, 194. |

2 | RLC, i, 196b. |

3 | Adam of Eynsham, Magna Vita Sancti Hugonis, ed. D.L. Douie and D.H. Farmer, 2 vols (2nd ed., Oxford, 1985),ii, 142-3. |

4 | RLP, 134, assuring its recipient that he should come 'ita parati quod honorem inde habeatis'. |

5 | RLC, i, 196. |

6 | John Gillingham, 'Richard I, Galley-warfare and Portsmouth: The Beginning of a Royal Navy', Thirteenth Century England VI, ed. M. Prestwich and others (Woodbridge, 1997), 1-15. |

7 | Nicholas Vincent, 'A Forgotten War: England and Navarre 1243-4, Thirteenth Century England XI, ed. B.K. Weiler (Woodbridge, 2007), pp.109-46; idem, ‘Jean sans terre et les origines de la Gascogne anglaise : droits et pouvoirs dans les arcanes des sources’, Annales du Midi, cxxiii (2011), 533-66. |

8 | Rotuli de Liberate, 165, ‘cuidam nuntio de Baiona quem dominus rex percussit’. |

9 | For John writing to the 'xii iuratos et ad consilium de Bayona', see Rotuli de Liberate, 166. |

10 | RLC, i, 195b: ' Mandamus vobis quod iuretis stare mandato ecclesie et pacem seruare saluis iure et dominio nostro sicut nobis mandauit dominus legatus Franc(ie) quod vobis significaremus'. |

11 | RLP, 133b. |

12 | RLC, i, 196b. |

13 | John's charter to Bayonne is known only from an early-modern copy in Gascon French: Bayonne, Bibliothèque Municipale, Archives de la Ville AA1 fos.ii-v verso (28r), whence Ibid. AA2 fos.2-9r (a copy of 1729, and Paris, Bibliothèque nationale ms. Français 3382 fo.6r. It is printed by J. Balasque and E. Dulaurens, Études historiques sur la ville de Bayonne, 3 vols (Bayonne, 1862-75), i, 452-3, and thence in the Livre des établissements, ed. E, Ducéré and P. Yturbide (Bayonne, 1892), 16 no.4, with a calendar in Les Chartes de franchises de Guienne et Gascogne, ed. M. Gouron (Paris, 1935), 116 no.311. For John's charter to La Rochelle, 8 July 1199, too early to have been preserved in the surviving Charter Roll 1 John, see G. Pon and Y. Chauvin, ‘Chartes de libertés et de communes de l’Angoumois, du Poitou et de la Saintonge (fin XIIe-début XIIIe siècle)’, Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest, 5th série 8 (2002), 61-4, at pp.72-4 printing a further charter addressed to the mayor and commune of La Rochelle concerning military service, 31 December 1208, again not in RC. |

14 | For London, see Diary and Itinerary, forthcoming for 3-9 May. |

15 | RLP, 133b-4, and for the prisoners taken at 'Bourg', see Diary and Itinerary 24-30 August. |

16 | RLC, i, 196, and cf. RLP, 133b. As early as July 1202, the Pope had threatened John with an interdict upon his lands in France following attacks by the King made against the bishop of Limoges: Receuil des historiens des Gaules et de la France, ed. M. Bouquet and others (Paris, 1738-1904), xix, 416-17, papal letters of July 1202 ('Utinam gemitus et dolores') noticed by a local historian, L'abbé (F.) Arbellot, 'Lettres inédites d'Innocent III', Bulletin de la Société archéologique et historique du Limousin, iv (1852), 143, whence wrongly cited as if provoked by events and letters of April 1215, by A. Lecler, 'Histoire de l'abbaye de Grandmont', Ibid., lviii (1908), 92-3. |

17 | RLP, 134. |

18 | RC, 206-6b. |

19 | RLC, i, 203b. |

20 | RLC, i, 197, where this entry, dated 27 April is reported as having been moved to the (now lost) Fine Roll. The only Fine Roll surviving for the year 16 John (May 1214-15) is that associated with the administration of Peter des Roches, itself petering out in the autumn of 1214 with the King's return to England: Rot. de Oblatis, 526-50. |

21 | |

22 | RC, 206-7. |

23 | RLP, 134; RLC, i, 196b: 'Hic recepit W. Cucuel rotulos custod(iendi)'. |

24 | As noted by V.H. Galbraith, Studies in the Public Records(London 1948), 80 (although failing to remark the coincidence between the new membranes on all three rolls), and cf. RLP, 137b, letters of 20 May with a postscript, apparently from the King: 'Saluto vos Will(elm)e Kukke Wel'. For William, presented by King John to the church of St Nicholas Gloucester, see Pleas of the Crown for the County of Gloucester .... 1221, ed. F.W. Maitland (London, 1884), 108 no.456; Rolls of the Justices in Eyre …. for Gloucestershire, Warwickshire and Staffordshire, 1221, 1222, ed. D.M. Stenton, Selden Society, lix (1940), nos. 82, 99, 165, 216c, 269. |

25 | For the meeting at Stamford, see the sources translated as part of the Feature of the Month, 'Dating the Outbreak of the Civil War, April-May 1214'. |

26 | RLP, 134. |

27 | RLP, 134. |

28 | RLC, i, 195b. |

29 | RLC, i, 195b-6. |

30 | RLC, i, 196b. |

31 | RLC, i, 198 |

32 | RLC, i, 196. |

33 | RLC, i, 196. |

34 | RLP, 134. |

35 | RLC, i, 195b-6, and for Nicholas de Breauté's house, cf. RLC, i, 197. |

36 | RLP, 133b, 'Ita quod nisi tunc gratum nostrum de predicto debito fecerint, idem frater G. Brochard' illud nobis per litteras suas significabit et extunc nobis facient gratum nostrum in Angl(ia)' |

37 | RLC, i, 196, and for Louvain, see also Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc., or Rymer’s Foedera, 1066-1383, ed. A. Clarke et al., vol. 1, part i (London, 1816), 106. |

38 | RLC, i, 196b, and for the negotiations of 1212-13, see Foedera, 105, 107, 113-14. |

39 | RLC, i, 196b. |

40 | RLC, i, 203-3b. |

41 | F.M. Powicke, ‘Alexander of St Albans: A Literary Muddle’, Essays in History Presented to Reginald Lane Poole, ed. H.W.C. Davis (Oxford, 1927), 246-60. |

42 | These letters over Master Alexander will form the subject of a feature of the month by Julie Barrau, forthcoming. |

43 | RLP, 134. |

44 | RLP, 134: 'Rex Hug(oni) de Lascy etc. Sciatis quod Walterus de Lascy frater vester finem fec(it) nobiscum pro vob(is) quod terram vestram de Ulton' vob(is) redderemus. Et quoniam tamdiu est postquam finem illum fecit et illum nob(is) non tenuit, licet illum posset tenuisse, cum postea tempus longum sit transactum, et cum postea diucius proprius vos (?recte nos) fuerimus nec finem illum erga nos teneri procurastis, decetero aliud inde facere non possumus nisi ut de predicta terra de Ulton' quasi de terra nostra commodum nostrum faciamus'. No mention of the fine referred to here survives on the Fine Rolls. |

- February 1214 - June 1214 (1)

- June 1214 - July 1214 (3)

- July 1214 - August 1214 (4)

- August 1214 - September 1214 (5)

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

3 August 1214 - 9 August 1214 - John plans his return to England

10 August 1214 - 16 August 1214 - John’s spies intercept a letter of Aimery of Thouars

17 August 1214 - 23 August 1214 - John refuses to abandon his French lands

24 August 1214 - 30 August 1214 - John grants a truce to Philip Augustus and seeks the release of William Longespée

31 August 1214 - 6 September 1214

- John hears of Bouvines and reconsiders his position

- September 1214 - October 1214 (4)

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

7 September 1214 - 13 September 1214 - Peace with Philip Augustus

14 September 1214 - 20 September 1214 - John’s chancery staff departs for England

21 September 1214 - 27 September 1214 - John demonstrates his willingness to rule according to law

28 September 1214 - 4 October 1214

- Negotiations with Philip Augustus

- October 1214 - November 1214 (4)

- John prepares for his passage back to England

5 October 1214 - 11 October 1214 - John’s sea journey and landing at Dartmouth

12 October 1214 - 18 October 1214 - The regency government of Peter des Roches

19 October 1214 - 25 October 1214 - From the Tower, John sends a coded message to his queen

26 October 1214 - 1 November 1214

- John prepares for his passage back to England

- November 1214 - December 1214 (5)

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

2 November 1214 - 8 November 1214 - The matter of episcopal elections

9 November 1214 - 15 November 1214 - John grants freedom of election

16 November 1214 - 22 November 1214 - John visits Wiltshire

23 November 1214 - 29 November 1214 - King John prepares for Christmas and intimidates electors

30 November 1214 - 6 December 1214

- Drama and jokes at Bury St Edmunds

- December 1214 - January 1215 (4)

- January 1215 (4)

- February 1215 (4)

- March 1215 - April 1215 (5)

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

1 March 1215 - 7 March 1215 - John's fears of French invasion abate

8 March 1215 - 14 March 1215 - John moves to secure the frontier zone

15 March 1215 - 21 March 1215 - John hunts in Nottinghamshire

22 March 1215 - 28 March 1215 - John prepares for trouble in the North

29 March 1215 - 4 April 1215

- John takes the cross, on Ash Wednesday

- April 1215 - May 1215 (4)

- May 1215 - June 1215 (5)

- 'our barons who are against us'

3 May 1215 - 9 May 1215 - 'by the law of our realm or by judgment of their peers'

10 May 1215 - 16 May 1215 - The rebels seize London

17 May 1215 - 23 May 1215 - John negotiates with the Pope and archbishop Langton

24 May 1215 - 30 May 1215 - Negotiation with the rebels

31 May 1215 - 6 June 1215

- 'our barons who are against us'

- June 1215 - July 1215 (4)

- July 1215 - August 1215 (4)

- August 1215 - September 1215 (5)

- September 1215 - October 1215 (4)

- October 1215 (4)

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

4 October 1215 - 10 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week one

11 October 1215 - 17 October 1215 - Rochester week two, the siege of Norham and the return of Giles de Braose

18 October 1215 - 24 October 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week three

25 October 1215 - 31 October 1215

- A meeting with the Cistercian abbots

- November 1215 - December 1215 (5)

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

1 November 1215 - 7 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week five

8 November 1215 - 14 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week six

15 November 1215 - 21 November 1215 - John and the siege of Rochester: week seven

22 November 1215 - 28 November 1215 - The fall of Rochester Castle

29 November 1215 - 5 December 1215

- John and the siege of Rochester: week four

- December 1215 - January 1216 (4)

- January 1216 (3)